Cry Elmina Captures Humanity of Slaves

When Vanessa Quainoo traveled to Ghana, West Africa, two years ago with her husband, Joseph, and their three sons, the communication studies professor had no idea the lasting effect a one-day tourist excursion to the ancient castle of Elmina would have on her.

While Joseph, a native of Ghana, traveled there for his work as bishop of the New Covenant Church International, Quainoo planned to research communication patterns of indigenous women and African women in leadership positions and do some sightseeing. The family trip to the castle from which many Africans were shipped off into slavery reshaped some of her personal and professional focus.

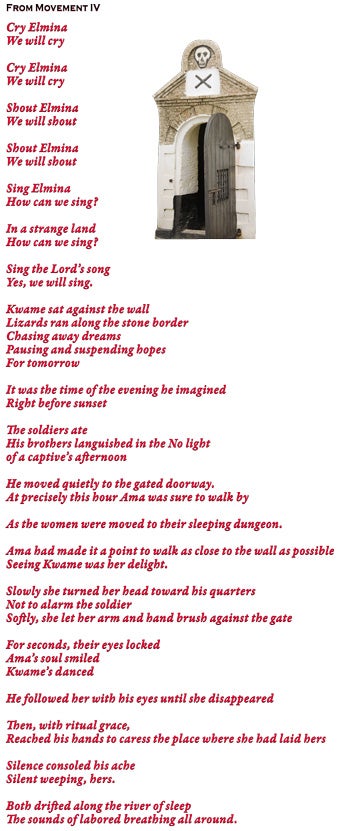

Quainoo, who has studied African-American history and specializes in African-American rhetoric, said she heard the calls not just of her children as they braced against the wind outside of the castle, but she also heard the history and pain of oppression inside the hallways as she brushed her fingers against the prison bars,

“I imagined and heard an entire story of two young people, a man and woman, who could not speak to one another because they did not share a common language and because the guards and structures in place would not permit them to speak. Yet, they had fallen in love, and that love had inspired their hope and endurance.”

“I imagined and heard an entire story of two young people, a man and woman, who could not speak to one another because they did not share a common language and because the guards and structures in place would not permit them to speak. Yet, they had fallen in love, and that love had inspired their hope and endurance.”

Back home in Rhode Island, she felt she had never left the castle—or the castle had never left her.

She wrote feverishly to share the story. “I couldn’t stop writing and writing. It just poured out of me, as though I was the only one to bring a voice, to share the passion and the pain of the experience. The walls of Elmina were weeping.”

The result is a book-length poem called Cry Elmina. Written for performance in a readers’ theater format, the poem tells a story of two main characters, Kwame, a young male captive from a village south of Elmina, and Ama, a young woman from a village north of the town. They spot one another amid all of the chaos and form an immediate bond that grows in spite of not being able to speak one another’s language or to be together. Through the use of flashbacks, Quainoo reconstructs their individual histories, showing the reservoir from which they drew strength and courage.

Cry Elmina explores the socio-psychological stresses that likely would have been experienced by West African captives who were held before being sold into slavery and shipped across the Atlantic to Europe and the West Indies.

Last spring, Quainoo was invited to present her poem at a conference hosted by the University of Cape Coast as part of the 50th year anniversary of Ghanian independence and rule over the castle. Her presentation was held in the castle with five graduate students from the host university.

Quainoo brought her story to life for an audience of Elmina Castle curators, students, and guests. With student actors and with the participation of her sons, the audience saw, felt, and heard the sounds that Quainoo had sensed. It was a strikingly visual experience, with the black cast against the starkly white castle.

“Those who had passed through this castle were people we don’t know anything about. They were not the historic figures we may have read about. They were just the pawns, caught and destined for slavery,” said Quainoo. “But these people were mothers having babies, they were children torn from their parents, kids who had been taken midstream from their ‘Mana,’ an African word that means Mother.”

Keenly aware of American and African-American history, Quainoo said historians, poets, and even filmmakers have reconstructed the transatlantic journey of the Africans, known as the Middle Passage. Yet, there has been little, if any, attention given to the lives of the captives before the passage.

“As an African-American scholar and teacher, I had often felt a need to apologize for privileging the oral-based focus of my rhetorical research. My experience with Cry Elmina has changed that. It has been a liberating affirmation of oral-based cultural history and communication. The process allowed me to merge my academic and creative expertise for the purpose of telling the story and contributing to the African-American narrative.

“So much of this history is untold. While I know this is fiction, it is rooted in the facts of the past that are not really discussed or described in American history books. This is the root of the African-American experience. It is from Elmina that so many of our forbearers became enslaved and were shipped to the Americas and other countries. This history is fundamental to all of our cultures. While Elmina represents the suffering of African slaves, it is a symbol for all oppression and suffering.”

By Jhodi Redlich ’81

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus