Designing for the Sea and Stars

To design a garment that anticipates the needs of future female explorers of sea and space, Professor Karl Aspelund and his student design team have taken one of the most ubiquitous items in present-day women’s fashion and given it a 16th-century upgrade.

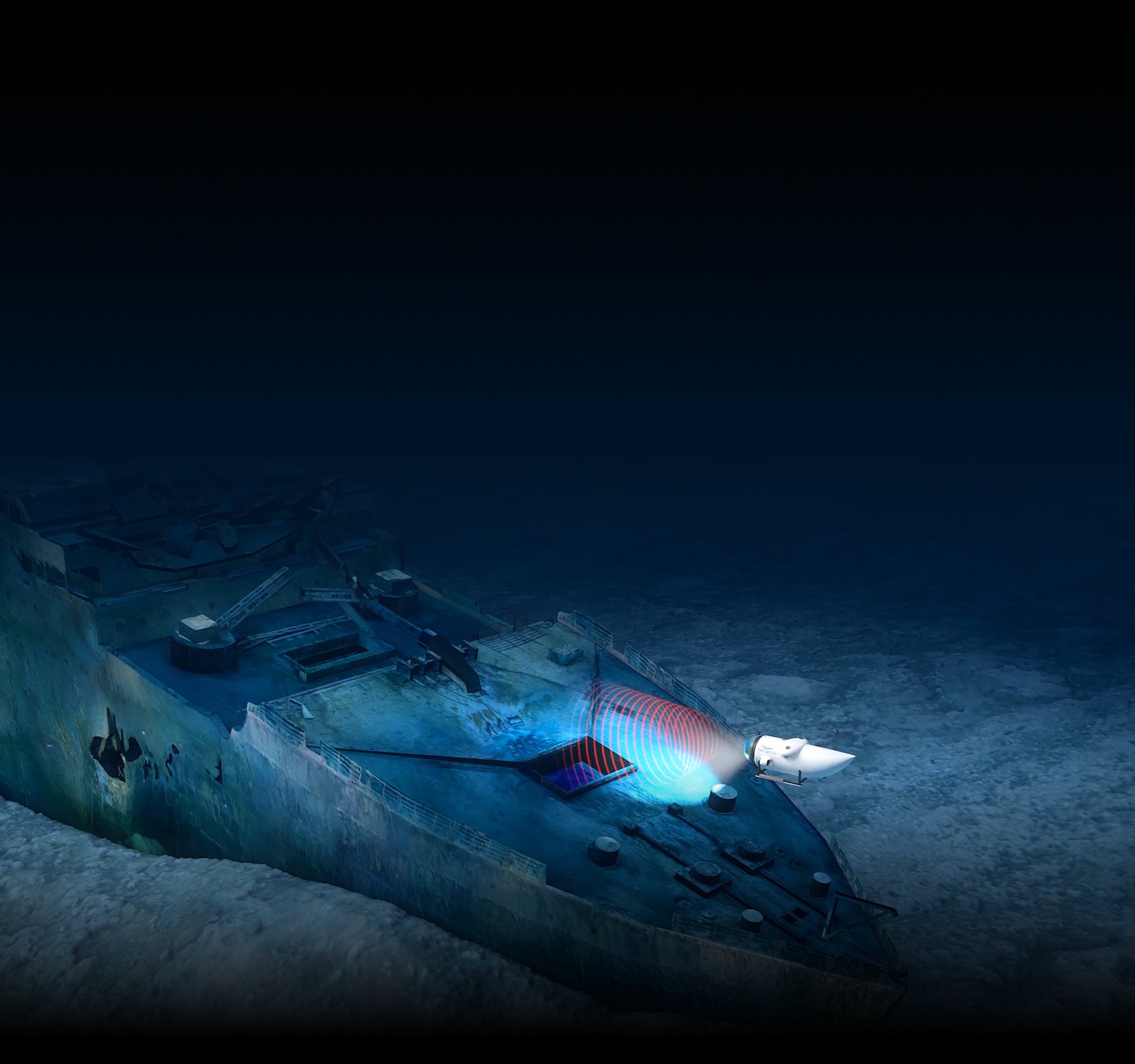

Imagine you’re an underwater archaeologist on an eight-hour dive in a submersible headed to the wreck of the Titanic. You’re sharing a capsule not much bigger than that of a small SUV — with four other explorers. You can’t stand up. You have limited space to move around.

And you need a bathroom.

But there isn’t one. And to further complicate things, you are a woman in a zip-front flight suit that requires near-removal to relieve yourself. So, what do you do?

It has happened, it happens, and it will happen again that women scientists’ work places them in situations where lack of forethought for their needs puts them in uncomfortable positions, figuratively and literally. Underwater archaeologist Bridget Buxton, associate professor in URI’s history department, can attest to it. In oceanography, clothing tends to be male-oriented and military in design. In talking with female researchers who worked in extreme environments as well as women in the Navy, Buxton learned that women who wanted to be accepted as equals didn’t complain about less than ideal arrangements for female anatomy, periods, hygiene needs, and privacy.

Buxton is the chief science coordinator for the 2019 OceanGate Titanic Survey Expedition to be held next June. When asked to submit her “male” size for a submersible flight suit, Buxton proposed an alternative plan for herself and fellow explorer and graduate student Morgan Breene ’14. “We just decided to own the fact that we have a different set of needs from our male colleagues and do something about it,” Buxton said.

She contacted Karl Aspelund, associate professor in the College of Business’ Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design, and asked him to create an alternative suit. Years earlier, Buxton had attended a lecture Aspelund gave on clothing design for long-distance space flight and been impressed.

“As someone who studies the history and culture of long-distance navigation, I understand that it’s not just about the technology,” Buxton said. “There has to be a culture and mindset of successful remote distance voyaging: some cultures and individuals have it, but most don’t. Clothing is one of those cultural factors that probably affects us in many ways that are very difficult to quantify, but the consequences are real and significant.

“Replicating the culture of successful long-distance voyagers and explorers will be critical to our long-term survival as a species, and this is where humanity’s forays into deep space and deep ocean exploration overlap,” Buxton added.

To design a garment equally suited to the ocean’s depths and the outer reaches of space, Aspelund and a team of students — Samantha Myette ’19, Rowan Talbot-Guerette ’18 and Maria Vazquez MS ’18 — looked backward, to the 16th century and an innovation in men’s fashion at the time: breeches.

Looking backward to move forward

The irony of futuristic travel is that it, by necessity, must model a medieval model of community, Karl Aspelund noted. “A small group of people trying to create a community in a hostile environment: It’s a question of economics. It’s the idea that somebody’s got to peel the potatoes,” Aspelund said. “You have to ensure knowledge is not only kept but transmitted — an apprentice-master relationship. There’s your social and economic structure.

“So the potato peeler is third stand-in for the gardener and is also the physician’s apprentice. Welcome to 1310.”

These are the thoughts that preoccupy Aspelund, who, in addition to teaching, serves as a member of the 100 Year Starship research team, a diverse group of experts from across the country dedicated to making travel beyond our solar system possible within 100 years.

For Buxton’s garment, Aspelund tapped then-senior Rowan Talbot-Guerette ’18, an anthropology and biology major whose Capstone Project examined women’s biological needs in space travel, and Samantha Myette ’20, an anthropology major and the first student to pilot a Design Thinking minor. Myette is working on an independent study this fall, planning apparel and textiles for a 900-day mission to Mars.

Talbot-Guerette shared with the professors her Capstone research on the challenges and constraints female NASA astronauts have encountered and endured. Though women, being smaller, are more suited to space travel in some respects, technology and clothing developed for space travel was designed with men in mind, Talbot-Guerette said. She cited a 400-page NASA report on health concerns in space travel, of which only four pages are devoted to gynecological health issues. To make themselves competitive with men, women astronauts have suspended their periods with birth control or undergone hysterectomies — Talbot-Guerette noted. Or they’ve been excluded altogether. Only 11 percent of those who’ve traveled to space have been women, according to NASA records.

Ignoring female health and hygiene issues or prohibiting female crew members from space exploration won’t work too well if colonization elsewhere is the goal, though. Voluntary hysterectomies or suspension of periods with birth control would thwart the mission. So examining hygiene products’ usage in space — the tampon needs of one woman on a three-year space mission, for instance, is 1,080 tampons at a cost, adjusted for space travel, of $146,400 — and designing clothing that accommodates needs becomes essential. In other words, the potato peeler who is also the third stand-in for the gardener and the physician’s apprentice might also need be the Eve to another crew member’s Adam if colonization is the goal. “We still need to consider what it means to be human in space,” Myette said.

“People don’t want to talk about birth or death in space. It’s still kinda taboo. Humans, we’re really messy. We can’t just work like robots,” Talbot-Guerette said. “We have to factor relationships, emotions, personalities, and cultural differences into the way we create systems.”

And bathroom breaks. Those, too, must be factored in.

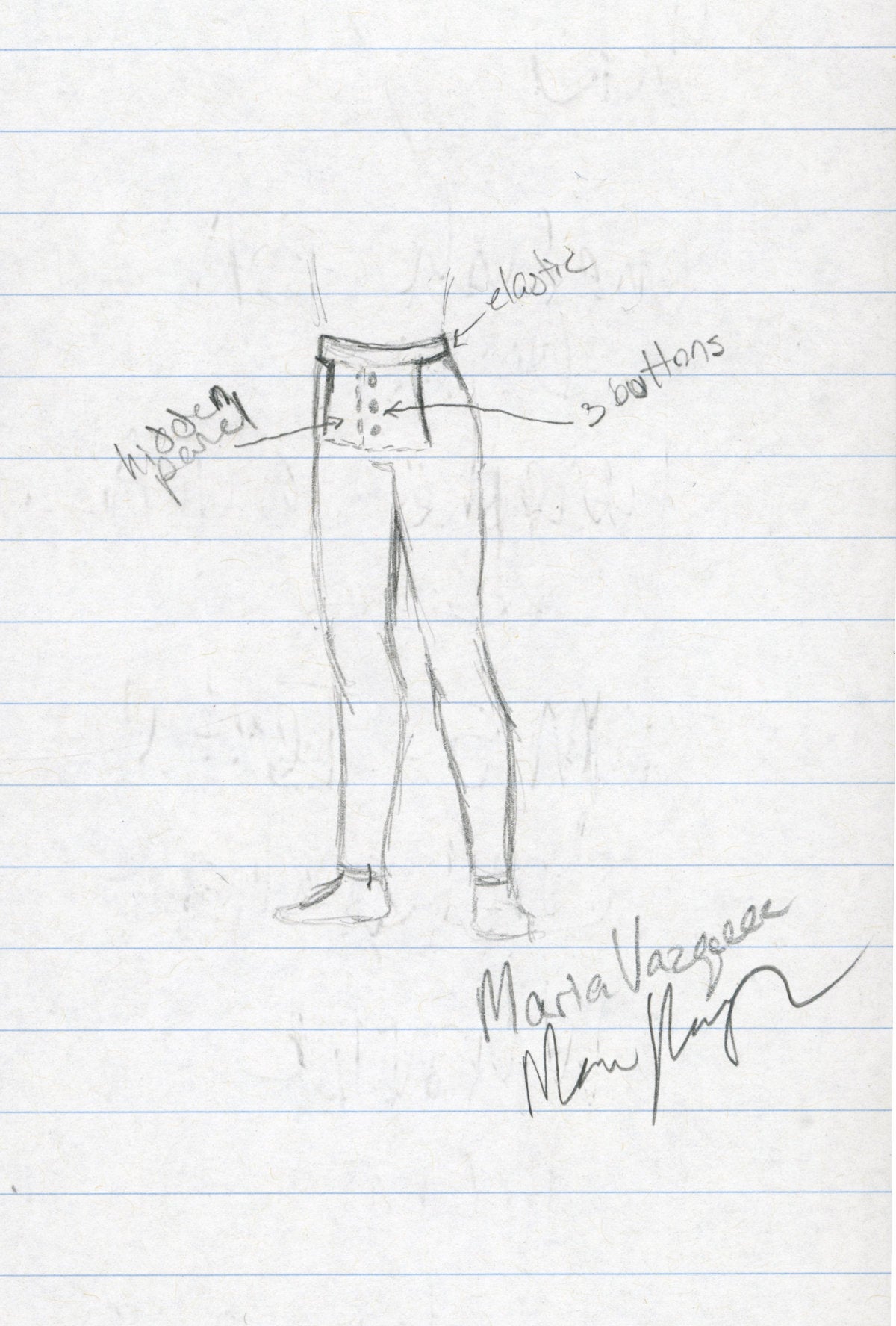

Myette, who’s been studying textiles and sustainability since a high school trip to Ghana, hit upon the essential concept: leggings with a skirt overlay, a staple of her mother’s wardrobe. The skirt would act as a shield, ensuring privacy; the leggings, comfort, and femininity — all wishlist items for Buxton. But how to keep the garment mostly on in the most private of moments? The team looked to men’s breeches for the answer. The earliest breeches, which replaced men’s hosiery back in the 16th century, have button fronts that allow for bodily functions to be performed without removal of the entire garment.

Outfitting a ‘feminist rebellion’

Aspelund emailed textile conservator and master seamstress Vasquez about creating leggings with the functionality of breeches. Vasquez accepted the challenge, happy to participate in what she termed a “feminist rebellion.”

Vasquez has been sewing for more than a decade. Her mother had sewn her dresses when she was younger but drew the line when Vasquez asked for a quilt. “I wanted that quilt,” Vasquez said and smiled. She ended up making a 963-triangle birthday quilt for her mom.

For the dive suit, Vasquez looked for a fabric that was comfortable, breathable, and flexible (allowing for bending over without bulking at the waistband).

Vasquez drew upon her knowledge of textiles — she worked in a fabric store for eight years — and pattern-making skills. “I looked at fiber content. I can tell by touch how things are made and if it would work. The pattern itself, I was completely comfortable with my pattern. Breeches haven’t changed much in 150 years.”

A history buff, equestrian, and cosplayer, Vasquez settled on the design of fall-front breeches whose button flap is hidden by a panel. “Once I knew how it would work, it was easy,” she said.

Vasquez once constructed seven giant jellyfish for a Mystic Aquarium gala out of 2,000 yards of tulle, fabric, streamers, and lights. So fall-front breeches were, indeed, easy. She had them done in a week.

From concept to completed garment was a mere three weeks. “I’m almost a bystander,” Aspelund said. “The students were already in place and these are women who know what they’re doing. It was a true collaborative effort.

“Textiles and apparel are unlike a lot of disciplines because what you have here is not a single focus. In one department you have people who know how to make things, you have historians, you have people who understand marketing and merchandising and promotion,” Aspelund said. “You have anthropologists, the design side, conservationists. We’re a world of our own. And with such a diverse crew with short communication lines, things can happen very fast.”

Vasquez’s characterization of the project as a “feminist rebellion” isn’t that far off the mark. You could say the leggings represent liberation for someone such as Buxton, who has been the recipient of more than one ill-fitting suit over the course of her professional life. Added insult: Women’s gear costs more.

“Retailers get away with this because enough women knowingly or unwittingly agree to pay more for the same product, just as women often get paid less for the same job. It’s illogical, but culturally it’s just where we’re at right now,” Buxton said.

Apart from its utility, this modest garment is an innovation that could have big — and beneficial — implications not only for female scientists and researchers but for the advancement of science and society as a whole.

“It’s no surprise that the fear of 377 atmospheres of pressure at the site of Titanic is a lot less ‘real’ to most people than anxiety about having to go to the toilet next to four strangers — and to women in particular, because our cultural experience of public toilets is typically not ‘public’ in the way male urinals are. So, either we mock and ignore our cultural and gender differences, or we acknowledge and address them,” Buxton said.

Only the latter course leads to an intelligent utilization of the critical scientific and cultural resources that women represent.”

Vive la révolution.