The very first discovery of a plant fleeing from a plant-eating predator was reported by news media around the world, as far away from Kingston, Rhode Island as the Himalayan Times, and translated into several foreign languages. And it was a discovery made at URI.

With their students, URI marine scientists travel the world aboard research ships to such far-flung places as the Sargasso Sea, the coast of Alaska and Antarctica to study the diversity and distribution of diatoms, single-celled organisms found abundantly in every water body on Earth.

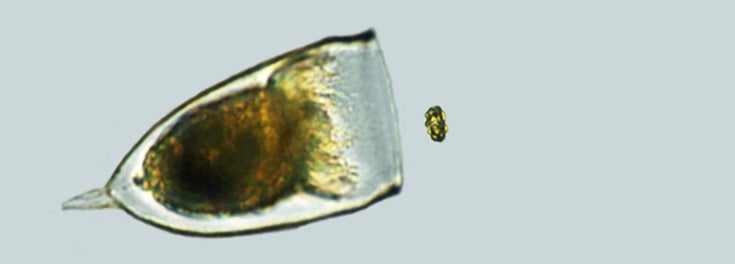

We don’t typically think that plants can run away (or swim away, in this case) to avoid being eaten, but that is exactly what URI Oceanographer Susanne Menden-Deuer and her graduate student Liz Harvey discovered during their study of some of the smallest organisms in the oceans – phytoplankton and zooplankton. These microscopic creatures are vital links in the marine food chain and play an important role in climate change, so understanding their ecology is critical to understanding the health of the marine environment.

The phytoplankton (the little one in the photo above) – about to be eaten by a zooplankton (the big one in the photo above) – could clearly sense the predator was there, said Professor Menden-Deuer. “They even flee from the chemical scent of the predator. We don’t know of any other plants that do this.”

In fact, at URI, a whole cadre of faculty and students at the Graduate School of Oceanography are studying these tiny creatures. They’re the most numerous organisms on the planet, but we know almost nothing about how individual species function. Researchers like Professor Menden-Deuer, Liz, and others, are bound to make exciting discoveries.

Marine Scientist Lucie Maranda is examining the role of plankton in biofouling – or the accumulation of microorganisms on wetted surfaces, like the way barnacles attach to pier stanchions, only much, much smaller. Fellow scientists Edward Durbin, Karen Wishner, and Robert Campbell study zooplankton in the Arctic and elsewhere. And Professor Ted Smayda is one of the leading experts on harmful algal blooms.

Associate Professors Tatiana Rynearson and Bethany Jenkins are using gene sequencing technologies and DNA fingerprinting techniques to identify how plankton respond to ocean chemistry and to find the genetic variations among and within individuals. With their undergraduate and graduate students, they travel the world aboard research ships to such far-flung places as the Sargasso Sea, the coast of Alaska and Antarctica to study the diversity and distribution of diatoms, single-celled organisms found abundantly in every water body on Earth.

“Diatoms are incredibly diverse and survive in a remarkable variety of habitats,” said Professor Rynearson. Species that specialize in the open ocean with very limited nutrients use different metabolic strategies for growth than do species in coastal environments. “Discovering these strategies can give us clues to how they might adapt to future oceans,” Professor Jenkins said.

Their students are also working on one of the world’s longest running marine research projects. Every week since the 1950s, they tow a net behind a boat collecting plankton samples from Narragansett Bay to examine long-term changes in phytoplankton and zooplankton populations and nutrient cycling.

At URI, you can think very big about small things.

Photo Credit: Liz Harvey, Cynthia Rubin

Related Links:

Scientific American article: Marine Plant Flees Predator

The Living Ocean: Marine Plants Can Flee to Avoid Predators

NPR’s Living On Earth: Marine Plants That Flee Predators