From Masta to Legend

In 40 years, hip-hop has moved from city streets to stadiums, and has made multimillionaires of teenagers. But staying relevant in an industry that worships youth is nearly impossible. Unless you’re Duval “Masta Ace” Clear ’88, who, 30 years in, is still making music. His way.

Listen closely, so your attention’s undivided

Many in the past have tried to do what I did.

Just the way I came off then, I’m gonna come off

Stronger and longer, even with the drum off.

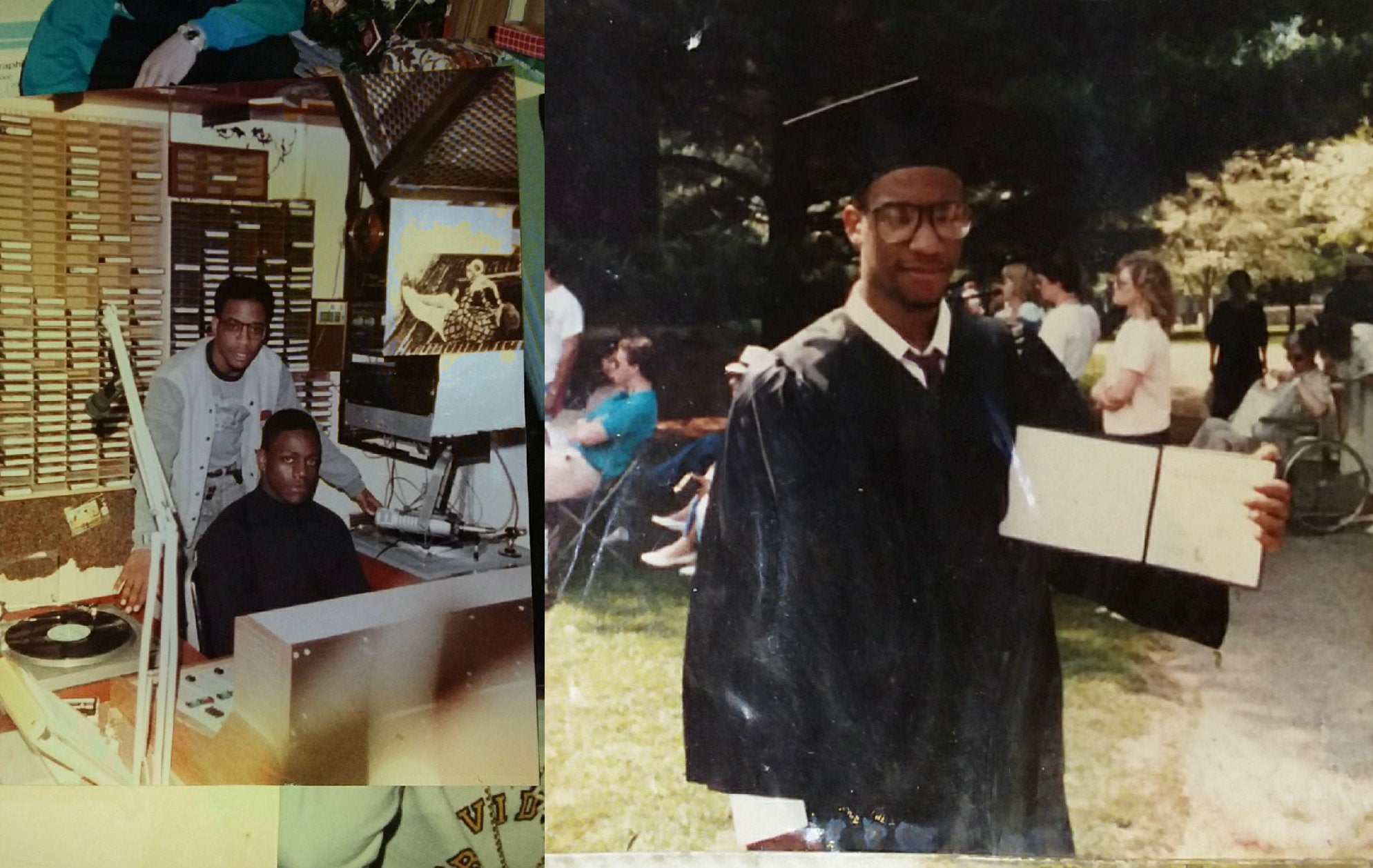

Christmas break, Brownsville, Brooklyn, 1985: Duval “Masta Ace” Clear, a marketing major in his junior year at URI, got a call from a friend, Scooter Rockwell. There was a rap contest in Queens. Kids in the neighborhood had entered. “You wanna roll with me?” Rockwell asked Ace.

“No,” Ace said. “It’s Christmas.”

Yvonne Clear, Ace’s mom, heard the exchange. “If you wanna go, go,” she told Ace.

“So I called my boy back,” Ace says. And he went. And, he won, beating 30 other rappers.

It was no surprise to his friend Dwayne “Steady Pace” Jamison, who went with Ace to the contest.

“I had a feeling. He was so smart,” Steady says. “We grew into hip-hop before we got into it. We were full-fledged into it — everything hip-hop. The neighborhood embraced it. We were listening to mixtapes. We were DJing in the projects. We were winning talent shows in school.”

The top prize was recording time in producer Marley Marl’s studio. This was big. Marl could get a kid someplace. Not that Ace was thinking about that. “I wasn’t thinking along the lines of a career. Hip-hop hadn’t spread to other cities and states, really. I thought, ‘If I get to record a demo and that demo gets played on the radio, that’s cool.’ But I returned to URI and focused on school.”

Ace wanted his prize, though. And it took some doing. He’d been calling Marl’s sister to schedule his demo. After nearly 4 months of phone calls, Marl’s sister started feeling sorry for Ace. “You know what, I’m tired of this,” she told Ace. “Here’s his number.”

Ace recorded music with Marl in 1986 and then, again, in 1987. In 1988, he graduated from URI with a degree in marketing. Ace says that back then he wasn’t thinking about being a career recording artist, but he was interested in getting a song put out. “In 1987 Marley played one of my demos on his radio show, WBLS Rap Attack with MR Magic, and the reaction I got from friends in the neighborhood made me want to put an official song out. I was fresh out of college,” Ace says. “My mom was wondering about job interviews. But I thought, let me just see how this goes.” Then the big break: Marl put Ace on hip-hop’s most famous posse cut, “The Symphony.” Suddenly Ace was rethinking career choices.

“Guys on the label were getting album deals; an album advance was $25,000. That was a lot of money to get in one lump sum. My mom was adamant that I start getting job interviews. As far as she could see, I wasn’t doing anything constructive,” Ace recalls. Yvonne laid it down. “She left me a note saying, ‘I want you out by your birthday,’ because I had started neglecting my household duties and chores due to my late nights in the studio and local clubs.”

Ace signed his first deal in November of 1990, got his $25,000, and moved out before his birthday. He never moved back. Never looked back, either. Thirty years later, Ace’s occupation is still what it was: recording artist. He has seven solo albums to his credit and five collaboration albums. Critics called his most recent award-winning album, 2016’s The Falling Season, one of the top albums of that year. Stratospheric fame and fortune have not been Ace’s fate, but he has the respect and admiration afforded only to the true artist. Recently, musician and movie star Donnie Wahlberg gushed via Twitter, “Always humbled when I’m in the presence of real #HipHop #royalty. Much respect to you @mastaace!” Oscar and Grammy award-winning rapper Eminem also counts himself a fan.

Thirty years into a career in a genre dominated by artists thirty years younger, Ace is an anomaly: a musician still making music, a songwriter still relevant to kids barely in their teens. Again, no surprise to Steady.

“My boy cares. About people. Period. And as an artist, he’s consistent. He is thought-provoking and he is knowledgeable about his role in society. He’s never compromised who he is. He stays the course, does things his way,” Steady says. “He doesn’t do what’s popular just because it’s lucrative. There’s not a lot of trustworthy people in this business. To be in it 30 years — he’s managed to build relationships because of his talent and who he is.”

Yeah, I was born son of Yvonne

Brownsville kid that wanna be on

Hit the streets, run and be gone

Outside with a curfew

Got lessons on honesty and virtue

And the people that’ll hurt you

Spanning just over a mile, Brownsville, Brooklyn showed a kid the choices he had. Ace lived in the Howard Houses. Elders like Ace’s nana, Mrs. Clear, the head of her building’s tenant patrol, kept an eye on Ace and his friends. Some of the neighborhood kids could get you into trouble. “They were more rowdy and took risks that got them on the wrong side of the law,” Todd Bristow, another of Ace’s childhood friends, recalls. “The threat was there, but people looked out for one another. Those were good times,” Bristow says.

“Jerry Harper, Ace, Chris, me, and Junior — we were the rat pack of 260 Stone Avenue, Howard Houses. Our building had a tenant patrol and Mrs. Clear was in charge. In the evening, she and the adults would talk and have coffee, play cards, and watch who came into the building.”

And Ace, in particular. An only child, he had his beloved mother, his grandmother, and his uncles keeping tabs. And a couple of known neighborhood bad guys, too. One guy, Smokey, did eight years in prison for murder. It was a case of street justice. Smokey went after someone who’d beaten his brother up. He couldn’t let that stand, even at the risk of doing time. A short, muscular type, a real tough street guy, Smokey was the neighborhood’s Napoleon. “Folks wouldn’t bother Smokey or his brother Larry,” Bristow recalls. “You stayed clear if you didn’t want to end up in any type of trouble. We’ve seen friends do really horrible things to one another, but the bad guys saw something special in Ace. Smokey made sure Ace got to school unharmed.”

Yvonne and Nana Clear were the real tough guys, though. “Duval’s mother, Yvonne, was a princess of a lady,” Bristow says. “She loved on everybody. And Mrs. Clear, she was the sweetest person you could meet, but if somebody got out of line — well — you’d see Mrs. Clear and do the straight and narrow. She was that grandmother figure who’s going to make sure everybody’s okay. That was Mrs. Clear,” Bristow says. “She was a woman of impeccable integrity.”

“I think Duval’s family values are at the core of his success, of who he is,” Bristow adds. “He treats people right. He didn’t sell out. His education helped him make good decisions. He’s not caught up in being rich.” Because Ace’s mom worked. Because Ace’s grandmother worked. Because Ace worked — at getting good grades, at football, at college and then, at rapping — when success came his way, he didn’t lose his head, didn’t succumb to greed like so many of his peers, Bristow says. “So many other cats, they were like, ‘I’m getting this money because I’m getting this money,’ and that got them caught up in illegal things. Ace had something wholesome to write about,” Bristow observes. “He started out self-actualized. He reached a sense of self earlier.”

The writing started early. Ace wrote his first poem in the fifth or sixth grade. Nana Clear saved it. “It was closer to rap than a poem,” Ace says. “Still, it was the first thing that she saved of mine, and it was an affirmation to me.” In seventh grade, Ace was asked to write a story on a standardized test. A couple of weeks later, the teacher who graded the tests spoke to Ace’s class about one particular story, praising the author for writing something so elaborate. It was Ace’s story. It was further validation. It was also as natural as breathing for Ace. “I was just doing what we did in the neighborhood. Rapping was like riding skateboards. It was about having a good time.” Ace had a lot of freedom, but he used it wisely. “I was one of those latchkey kids. I was left to my own devices a lot, but I didn’t fall into the negative stuff,” Ace says.

When it came time for college, Ace looked for places where he could play football. URI made the list, and Yvonne made the argument that Rhode Island was away, yet close enough for Ace to return home for a long weekend. “She didn’t really point me in a certain direction, but going to college was an absolute must. I considered taking a year off, but she said, ‘No, you’ll take a job and not go back.’”

End of discussion.

If I never recorded another song

If I was wrong, and nothing I spitted was ever strong (No regrets)

If I never perform at another venue

If this genuine love doesn’t continue (No regrets)

Ace looks at his career in phases. The first phase, 1988 to 1996, saw the release of three albums, Take a Look Around (1990), SlaughtaHouse (1993), and Sittin’ on Chrome (1995). In 1994, Ace recorded the title track of Spike Lee’s movie Crooklyn with MCs Special Ed and Buckshot of Black Moon. “From 1996 to 2000, I didn’t release any music at all. I was at a crossroads,” Ace recalls. “I thought my usefulness in the game had run out. I thought I’d become an executive producer.”

Ace’s misgivings weren’t unfounded. Most rappers have the career longevity of the average Victoria’s Secret model or NFL player. In the 2017 Emmy-nominated hit HBO series The Defiant Ones, famed rapper, producer, and billionaire Dr. Dre, 53, scoffs at the idea of releasing another album, calling rap a young man’s game. Ace is the exception. His popularity has been steadily growing since 2000, when he did a tour in Europe, 13 shows. “I couldn’t believe the turnout,” Ace says. “It renewed my energy.”

And commenced a wave of creativity that has resulted in some of Ace’s most critically acclaimed work. In 2001, he released Disposable Arts, considered one of the most important hip-hop albums of that year (and loosely based on Ace’s time at URI). Long Hot Summer followed in 2004. In 2012, Ace paid tribute to his beloved mother with MA_DOOM: Son of Yvonne, and in 2016, he dropped The Falling Season. Taken together, Ace’s work is at once an epic tale of a boy’s life and hip-hop at its best: a commentary on the toll modern society takes on black youth, says Marlon Mussington ’01, fellow URI grad and Ace’s friend since the 1990s.

“Hip-hop matters because it allows a culture of people who may not typically have a voice to speak,” Mussington said. “It speaks to what ails many communities of color. Certainly, it speaks to police brutality. You have an education system that may not be the greatest in communities of color. There’s voter suppression. Drugs.”

The things that put people off hip-hop: the misogyny, the homophobia, the vulgarity — these things must be placed in context, Mussington says. Hip-hop is art’s response to the intolerable.

“I can’t think of any other musical genre out there that’s as radical in its use of language as rap is. It might be hard to hear and people might get too caught up in the language to hear the pain behind it.” You have to pay attention, not just to the words, but to the message and the emotion behind the words.

Artists like Ace, who use their work to call out injustice, are finally getting the recognition they deserve, he says. Kendrick Lamar winning the 2017 Pulitzer and Hamilton winning a Pulitzer, 11 Tony Awards, and the Kennedy Center’s first-ever ensemble award — such honors are long overdue, Mussington says. “I’m excited because I feel as if rap music is now starting to arrive. It’s no longer just BET recognizing our artists,” he says. “And it wasn’t that our music wasn’t good years ago. It just wasn’t getting the respect it deserves.”

And Ace’s time has come, too. “Ace is such an important figure in the music industry,” Mussington adds. “He needs to be celebrated. He’s a pure artist.”

Man, it took me 15 years to understand my worth

It was 1988 when Marley planned my birth

Had to get my feet out of the sand and surf

Never thought that my rap lines would expand the earth

Now 51, Ace just released a new album, A Breukelen Story, with Canadian-born producer Marco Polo. In addition to his music, he’s also working on a play. Rich Ahee, his business partner since Disposable Arts, jokes, “We keep coming up with ways to prolong our careers.”

Ahee calls Ace the exception to the typical hip-hop artist. “He’s a humble, regular guy, a person of ethics and morals. I would say most artists are nice, most artists are talented, and a lot are professional. But it’s rare when you get all that in one person,” Ahee says. “He’s a person you’d invite to your house for dinner. He’s a person I needed to be friends with.”

Would Ahee call Ace a legend? “Yes. One hundred percent. He’s proven it through the last 30 years,” says Ahee. “There’s been artists who’ve had bigger commercial success than him, but he’s the only one who’s 30 years and seven albums in and doing it consistently. He’s reinvented himself for a whole new generation. His albums are only getting better. He’s one of the few guys who, every time he drops a new record, new fans come on board.”

Ace is humble when it comes to talking of legends.

“The term ‘legend,’ people use it too loosely,” he says. “I’m not able to be comfortable with the term because of the cavalier way people use it. People call artists legends after only two albums. So it’s hard for me to know what that even means these days. But I appreciate anyone who affords me that title.”

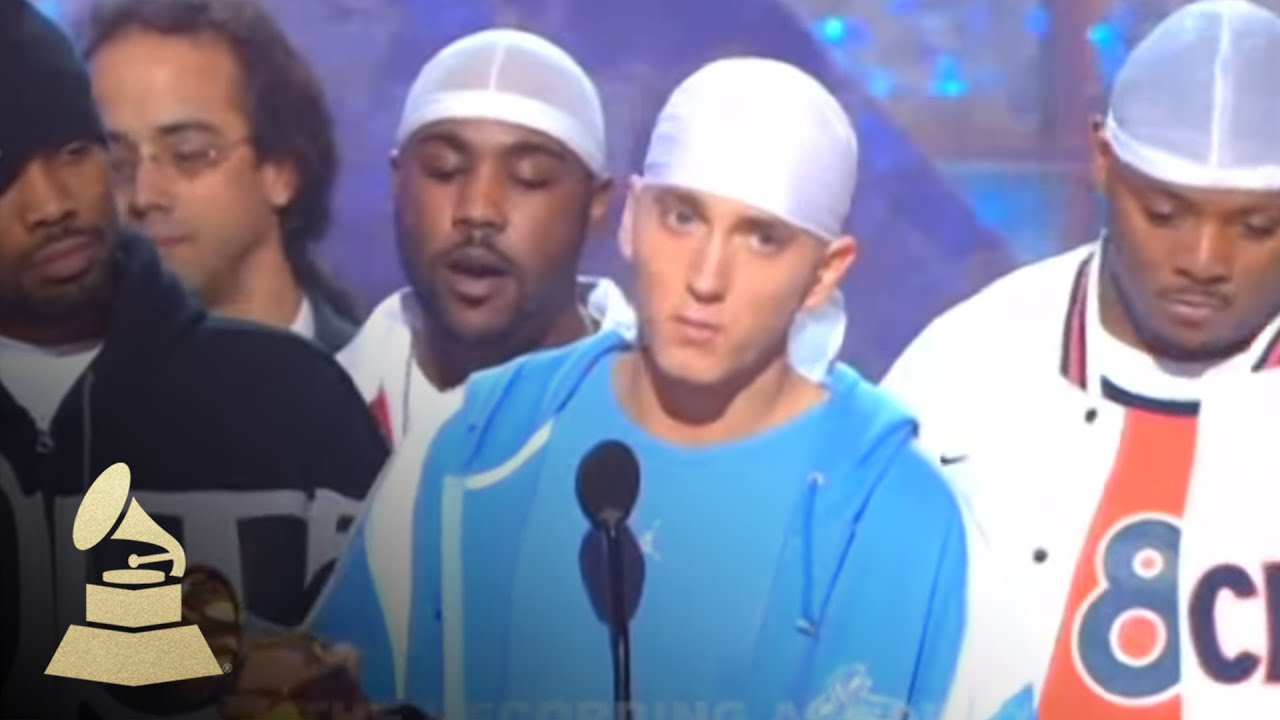

Eminem afforded him the title. The Oscar winner called Ace one of his primary influences in 2003 when he accepted his Grammy for best rap album for The Eminem Show. “I didn’t know him at all,” Ace says. “I’d heard rumors he was a big fan. When he said my name in his acceptance speech, it threw the world off its axis for me. Most of the names he mentioned in his speech were everyone’s influences, household names.

“It was a cool moment.”

A peak moment for some. But there have been many for Ace. URI being one. “I overcame a lot of obstacles to get to Kingston, R.I., to get to that campus. The fact that I came from the neighborhood I came from, that I made it out of despair — it’s unbelievable I got from there to here somehow.

“Now I’m traveling to Australia and Ireland, Spain and Iceland, Colombia and Brazil,” he said. “To have touched the URI campus was amazing, and then to experience the world, to explore these cultures, to perform for the people there: It’s just the most improbable journey, and the journey continues.”

A version of this story appeared in the University of Rhode Island Magazine, Fall 2018 issue.