Oh, no! You’ve been bitten by a tick or find one on your clothes or pet. Your anxiety quickly builds as you wonder, “Is this a deer tick? Will I get Lyme disease?”

With University of Rhode Island Professor of Entomology Tom Mather warning that a tough tick season is looming this spring and summer, he also wants you to know that help is as close as the Internet or cellular data by using his TickSpotters program.

With your smartphone or camera, simply take a photo of a tick that you find on your skin or clothes and send it to TickSpotters.

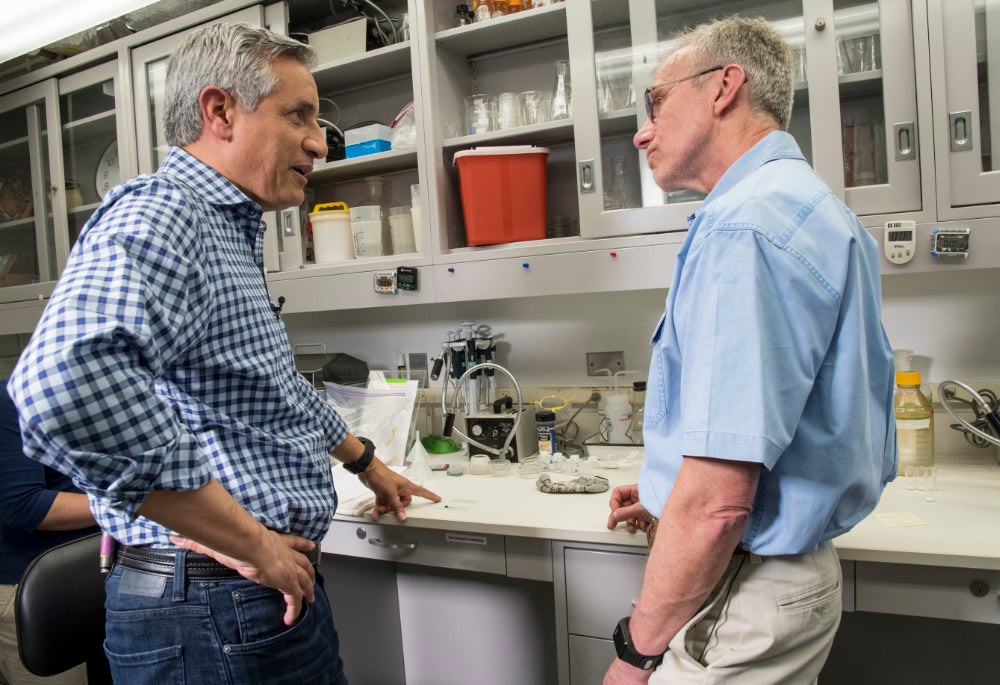

Mather, a nationally renowned tick expert, director of the URI Center for Vector-Borne Disease and its popular TickEncounter Resource Center, works with doctoral graduate student Heather Kopsco and other team members to examine photos and provide an identification confirmation, a personalized risk assessment and case-appropriate prevention educational information at no charge to help people determine what their next steps could be.

TickSpotters

Mather discussed TickSpotters, the prevalence of disease-carrying ticks across the country and steps people can take to prevent tick bites with NBC Nightly News medical correspondent Dr. John Torres.

The deer tick is particularly troublesome because besides Lyme disease it can transmit four other different types of germs, and during its nymph stage, it is the size of a poppy seed and difficult to spot. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, typical symptoms caused by an infected deer tick include fever, headache, fatigue, and a characteristic skin rash called erythema migrans. If left untreated, infection can spread to joints, the heart and the nervous system.

Since launching TickSpotters in 2014, Mather and his team have responded to more than 46,000 submissions, examined more than 35,000 pictures and provided information to those wondering if they are in danger of coming down with Lyme disease or other dangerous tick-borne diseases.

He and Kopsco view each submitted photo to determine whether the tick encountered is a deer tick, also known as a blacklegged tick, or one of the other six or seven most common human or pet-biting ticks found across North America.

“We respond by email with a detailed message confirming the type of tick, the tick’s stage of development, how long it was attached, the chance for some disease and best next actions to help prevent possible disease. For example, if your tick was an American dog tick, there is pretty much no chance for that tick to pass on an infectious dose of the Lyme disease germ, and in the Northeast, little chance for other diseases either. It’s not a diagnosis but it is an informed risk assessment.”

Last May, TickSpotters helped 3,400 people who submitted photos. One night this week, the team received 164 photo submissions, and so far this month, there have already been more than 1,000 submissions. “Not too surprising, since May is the “tickiest” month of the year across North America,” Mather said.

“People have sent us emails telling us that if they hadn’t come to us, they wouldn’t have taken action,” Mather said. “People sometimes take our reports to their health providers, and the doctors “can’t believe how helpful the information is.”

Submissions regularly come from all over North America and occasionally from international locations, including Japan, Cuba, South Africa and Europe. While most people in the northeast and mid-Atlantic states are concerned about deer ticks, these ticks are also commonly found in the upper Midwest and increasingly in the southeastern states. The Pacific coast has its own type, called western blacklegged tick. Deer ticks are widespread in Rhode Island and elsewhere, which Mather attributes to increasing numbers of deer appearing in suburban and even semi-urban backyards and along local roads. Deer are no longer restricted to the forests and fields in more rural areas.

“People tell us things like, ‘We’ve lived here for 15 years and have never seen ticks until now,’” Mather said.

“More than just a crowd-sourced tick survey, TickSpotters is also about building relationships,” said Mather, who is a member of the Northeast Center of Excellence in Vector Borne Disease at Cornell University and a member of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Lyme Disease Working Group’s prevention sub-committee.

“It’s an opportunity to listen to peoples’ tick encounter experiences and engage when they are most receptive to new ideas. TickSpotters is a great tool helping us better understand how to overcome barriers to prevention and maybe even start solving the growing tick problem.”

The TickSpotters team also is collaborating the TickReport program at the University of Massachusetts, where people can send their ticks for a fee to have them tested for the presence of disease germs.