The Woonasquatucket River flows over the dam at Rising Sun Mills in Providence.

Rhode Island’s rivers are as important to the state’s history, economy, and identity as the ocean waters they flow into. Long plagued by pollution and neglect, rivers have been the focus of revitalization efforts, and URI has played an important role. The future of our rivers—and all our waterways—depends on how we manage, protect, and respect them.

By Dave Lavallee ’79, M.P.A. ’87

On a bright, fall day in the Olneyville section of Providence, the Woonasquatucket River roars over a dam that once powered the National and Providence Worsted Mills. The former textile mills now house stylish apartments and commercial spaces, including a cafe and yoga studio. Alongside the river sit the hulking, rusted remnants of the sluiceway that once controlled the flow of water to the mills. A fish ladder, completed in 2007, allows 40,000 herring to return upstream each spring for spawning, a rite once prevented by the dam. On the opposite side is the popular Woonasquatucket River Greenway Bike Path, which follows the river from Johnston to Providence.

But the scene on the banks of the Woonasquatucket wasn’t always so idyllic.

“I moved to Rhode Island in 1988 and began work as a summer intern at DEM (R.I. Department of Environmental Management),” says Alicia Lehrer, M.S. ’93, executive director of the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council. Lehrer earned her URI graduate degree in natural resources science and developed the bacterial testing program for URI’s Watershed Watch volunteer water monitoring program.

“The river was right outside my office door, and my coworkers took me outside to see it,” Lehrer recalls. “They said, ‘This is the Woonasquatucket. It is really contaminated. Don’t go in there.’”

“There is really no comparison to the water quality now,” she says. “Until 2015, we had a lot of problems, including sewage from 19 combined sewer overflow pipes along the river.”

The remains of a sluiceway that once controlled the flow of the Woonasquatucket River.

Mallard ducks on the banks of the Woonasquatucket River.

The Narragansett Bay Commission

Combined sewer systems collect rainwater runoff, domestic sewage, and industrial wastewater in one pipe. Sometimes, during heavy rainfall, the runoff exceeds the pipe’s capacity and untreated water flows into nearby water bodies.

Thanks to the Narragansett Bay Commission, which owns and operates Rhode Island’s two largest wastewater treatment facilities—Field’s Point in Providence and Bucklin Point in East Providence—combined sewage overflow has been greatly diminished. Three major commission projects are noteworthy—a below-ground, 65 million-gallon, 3-mile tunnel that captures and holds sewage for treatment at Field’s Point; a system of near-surface pipes along the Seekonk and Woonasquatucket rivers to intercept overflows; and a 2.2-mile, 65 million-gallon tunnel to hold overflow before it gets to the Seekonk River. The commission broke ground on the last of these in 2021. By the completion of the final phase, combined sewage overflow discharges to the rivers are projected to decrease by 93%. Additional projects have reduced nitrogen loads from the Field’s Point and Bucklin Point facilities by 83%.

URI oceanography professor Chris Kincaid has worked with the commission since 1998, measuring and modeling the Seekonk and Providence rivers and upper Narragansett Bay, particularly for hypoxia, or low levels of dissolved oxygen. Hypoxia is caused by excessive nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorous, that lead to aquatic plant blooms and fish kills, like the one in August 2003 on Greenwich Bay, when a million dead fish washed ashore.

Field’s Point in Providence is one of Rhode Island’s two largest wastewater treatment facilities. URI oceanography professor Chris Kincaid has worked with the Narragansett Bay Commission, which owns and operates the facility, since 1988 to measure and reduce nutrients in the water that comes out of treatment facilities. Engineering professor Vinka Oyanedel-Craver assessed the baseline level of microplastics contamination at the facility.

Ashton Mill on the Blackstone River in Cumberland, R.I., produced muslin from 1867–1935, when it shut down during the Great Depression. The mill building now houses luxury apartments.

“There is a balance,” says Kincaid, who has collected 1 billion data points from the Seekonk and Providence rivers and the upper bay. “If you don’t have enough nitrogen, you starve the things that live in the water. But if you have too much nitrogen, you get a bloom of phytoplankton, algae, and grasses. When that material dies and settles to the bottom, detritivores, the organisms that break down the dead material, suck all the oxygen out of the water.

“After the Greenwich Bay fish kill, there was a rallying cry that this couldn’t happen again, but let’s make sure we understand the problem,” Kincaid says. “One of the first things that happened was treatment plants started using three-stage treatments to remove nitrogen from wastewater.”

“Narragansett Bay has one of the most extensive data sets in the world for coastal plumbing, or how water moves and flushes,” says Kincaid. “One of the reasons is the Narragansett Bay Commission’s support of science, data, and sound modeling. We have been working to balance ecosystem health with economic health, and to do that you need huge amounts of data to build accurate ecosystem modeling tools.

“Our most recent bay circulation models, improved through years of trial-and-error validation steps with data, show that managed nutrient reductions have been successful,” Kincaid says.

His simulations indicate that rivers and offshore intrusions—rather than sewage treatment plant inputs—now have the greatest impact on nutrient levels and blooms in the Providence and Seekonk rivers and in the upper bay.

“Before the 2003 fish kill,” says Kincaid, “treatment plants were discharging at 20 milligrams per liter concentrations for total nitrogen; now the concentration is 5 milligrams per liter coming out of the pipes.”

“Once rivers are loved and revered, investment follows.”Alicia Lehrer, M.S. ’93, executive director of the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council

Such efforts have had significant positive impacts. “Recently, we collected data that showed swimmable water quality at Riverside Park, which is in the heart of Olneyville, a heavily industrialized area,” says Lehrer. “The water is not consistently clean enough for swimming, but this was kind of like a miracle.”

A cleaner river has led to almost $1 billion in investment along the Woonasquatucket’s banks. Such developments as the Foundry Campus—a mixed-use property including residences and offices located in the former home of machine tool manufacturer Brown & Sharpe—now dot the river.

“Once rivers are loved and revered, investment follows,” says Lehrer.

The Blackstone River runs through the northeastern corner of Rhode Island and was once referred to as the hardest working river in America because it was home to hundreds of mills. It was also one of the most polluted rivers in the nation. Remediation efforts have made the river cleaner and more hospitable for people and wildlife.

The Blackstone River flows over a dam between Lincoln and Cumberland, R.I.

Rivers Foster Civilization

The region’s Indigenous people have long “loved and revered” local rivers.

Lorén Spears ’89, Hon. ’17, executive director of the Tomaquag Museum and a citizen of the Narragansett tribal nation, says, “We used rivers for transportation to trade and visit with other people. Food sources such as fish, turtles, and mammals were harvested from the rivers and their banks. We harvested plant matter like bulrush. Its seeds and roots are edible, and we wove stalks of the plant material for mats in our homes.”

The rivers allowed people to move from their winter homes to their summer homes. “We stayed in inland longhouses in the winter, and during the spring and summer we used the rivers to get to our homes near the ocean,” Spears says.

“This traditional ecological knowledge—including food, medicine, technology, and spirituality—of the rivers and other waterways is passed down to our people today,” says Spears. “We share this knowledge through tours at the Tomaquag Museum.”

URI associate professor of geosciences Soni Pradhanang, who takes an interdisciplinary approach to her work on managing water resources and protecting ecosystems, echoes Spears on the centrality of rivers in the lives of ancient people.

“Human civilization owes its start to the rivers of the world,” Pradhanang says. “You can’t irrigate with seawater. It’s no coincidence that the great Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures developed along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and the Nile.

“And ancient people lived in or near the rivers’ floodplains,” Pradhanang adds. “When the rivers flooded and receded, they deposited beneficial soils and sediments on the land that the people farmed.”

Rivers as Economic Engines

But centuries later, rivers became the engines that transformed Rhode Island into one of the richest states in the nation, as Samuel Slater and other industrialists built water-powered mills on them. Rhode Island’s rivers powered manufacturing giants including Fruit of the Loom, U.S. Rubber, and some of the biggest names in jewelry manufacturing.

The cost, however, was great as rivers became polluted with waste from inadequate sewage systems, residential cesspools, and toxins from the mills. The dams built to control water flow to the mills prevented migratory fish from returning to the rivers to spawn.

The revitalization of the state’s rivers in the past half-century is due in large part to the Clean Water Act of 1972, which, according to Elizabeth Herron ’88, M.A. ’04, director of URI’s Watershed Watch, required mills to pay for their pollution. The act empowered the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to implement wastewater standards for industry and made it unlawful to discharge pollutants into navigable waters without an EPA permit.

Elizabeth Herron ’88, M.A. ’04, director of URI’s Watershed Watch, on a pedestrian bridge that crosses the Saugatucket River in Wakefield, R.I.

Herron, like Lehrer, observes that the economy is strengthened when rivers, along with their affiliated ponds and surrounding lands, are clean.

“Canoeing, kayaking, fishing, and other recreational activities have increased because water is cleaner,” says Herron. “People are buying and renting boats, kayaks, and fishing gear.”

And the state’s bike paths, several of which run along rivers, including the Blackstone, Woonasquatucket, Pawtuxet, Ten Mile, and Saugatucket, “have led to more businesses that recognize the beauty and value of the bike paths and rivers,” Herron says. “Along the Washington Secondary Bike Path near Route 117 in West Warwick, ice cream and breakfast places have oriented their stores to take advantage of the bike path and the nearby Pawtuxet River.”

And cleaner rivers are not just good for business. “Eels, herring, eagles, beavers, otters, egrets, herons, and mink have returned to the rivers,” Herron says, adding that there are more trees lining rivers across Rhode Island today than there were 100 years ago.

“Forests and their accompanying leaf litter slow and filter rainwater as it moves to lakes, ponds, and rivers,” Herron says.

URI Engineers and Scientists Help Establish Cleaner Rivers

URI’s involvement in revitalizing the state’s rivers goes back decades. Raymond Wright, emeritus dean of the College of Engineering, worked closely with the EPA on a comprehensive report in 2001 after 10 years of study, showing the Blackstone River’s water quality had improved greatly. His Blackstone River Initiative report has been used as a model for other river studies. Wright conducted studies on the levels of nutrients, like phosphorous and nitrogen, as well has heavy metals like mercury, chromium, and lead in many of the state’s rivers.

“We collected data, which agencies like the EPA and DEM could use to develop regulations and water quality standards,” Wright says.

“Ray was a great supporter and mentor to me,” says Vinka Oyanedel-Craver, associate dean for research and professor of civil and environmental engineering—and one of the principal investigators with URI’s Water for the World Initiative. “I inherited his lab when I started at URI.”

One of her newest research projects involves working with the R.I. Department of Transportation (DOT) on street sweeping. Oyanedel-Craver calls the project a “nonstructural alternative” to addressing pollution in storm runoff.

“We are looking at the amount of dust and sand on the state’s roads and analyzing what is in those materials that could enter rivers, streams, and the bay,” she says. “DOT came to us for assistance in determining a schedule that would help reduce the load of pollutants entering bodies of water in an effective and economical way.”

She says sources of contaminants on the state’s roads include car exhaust particles and materials from tire and brake decay.

Pradhanang also notes Wright’s influence. “When I led the Scituate Reservoir safe yield research in 2017,” she says, “I contacted Ray to learn about the Scituate reservoirs and their hydrodynamics. He is rich in information and is always eager to talk about science related to rivers and reservoirs. The background he provided helped us with our project.”

Wright’s late colleague, professor emeritus of chemical engineering Stanley Barnett, and former chemical engineering research professor Eugene Park, Ph.D. ’94, received the Narragansett Bay Commission’s 2011 Pollution Prevention Environmental Merit Award for their work on finding sustainable, cost-effective solutions to environmental problems.

Barnett and Park helped Rhode Island businesses reduce and prevent pollution for 25 years and served as pro bono engineering consultants to more than 500 companies. They worked closely with the DEM, Narragansett Bay Commission, and the EPA to resolve pollution problems in industries such as metal finishing, textiles, and auto body repair.

Andrew McNulty, M.E.S.M. ’22, takes soil samples for a 2021 Department of Natural Resources Science project that mapped hundreds of acres of wetlands along the Pawcatuck River, which flows from Worden Pond in South Kingstown, R.I., to Stonington, Connecticut.

A More Sustainable Approach to Textiles

Textile mills and other factories were prime sources of river pollution, but URI textiles professor emeritus Martin Bide conducted research to help the industry reduce pollution. Now, Professor Karl Aspelund of URI’s Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design aims to work with a still-thriving—albeit, smaller—textile industry to reduce pollution.

“I am planning a long-term, multidisciplinary project that will, if successful, create a model for how to run a textile manufacturing operation with a minimal ecological footprint,” Aspelund says. “A textile mill in nearby Massachusetts has agreed to open its doors to us completely so a team can conduct business and engineering analyses and assess the mill’s wastewater treatment and environmental impact. It will be broad research that will also look at the sociological impacts on the community.”

The team will work on a manufacturing model that puts less waste into the air, water, and landfills and fewer plastic particles into the environment. Aspelund says it’s a winning proposition for the mills, including the handful of textile operations still running in Rhode Island, because they could end up with a model for how to “continue to manufacture for generations to come in a way that is ecologically sound.”

Aspelund’s project will include scientists who investigate groundwater and soil contamination. “This team has already developed an interesting way of using plant life, mainly trees, as biofiltration devices,” says Aspelund. “We’re hoping to get them in there to check the state of the soil and water around the plant, and to then work with local flora to clean the area—and keep it clean.”

In the Blackstone Valley

The 48-mile Blackstone River, which runs from Worcester, Mass., to Pawtucket, R.I., was once commonly referred to as the hardest working river in America because it was home to hundreds of mills.

Pollutants from the mills and other sources had, for many years, turned the river into an open sewer. The river was acidic—harmful for the ecosystem. “But now the water quality has improved greatly,” says Samantha Jackson ’22, director of education for the Blackstone Valley Tourism Council, adding that it has “a perfect pH, between 6 and 7.”

“I take a lot of seniors, people in their 80s and 90s, out on the river for tours, and they tell me you couldn’t go out on the river when they were young because it smelled so bad,” says Jackson, who leads tours on the Blackstone Valley Explorer riverboat. “The river was so polluted, and you couldn’t get a canoe in the river because there was so much trash. The seniors tell me the river ran from pink to purple and red to orange depending on the dyes being used in the textile factories.

“Our boat captains have been with us a long time, and they are seeing more and more wildlife, such as great blue herons,” Jackson says. “I saw a mated pair of eagles fishing in the river in Pawtucket.”

Central Falls Landing, a public space and dock where the tourism council is located, has become a gathering place where people launch canoes and kayaks. Like the Woonasquatucket, a prettier and cleaner Blackstone has spawned businesses like Shark’s Peruvian Cuisine, a bustling restaurant with an outdoor seating area overlooking the river.

“People should stop thinking, ‘seacoast, oceans, rivers, streams.’ It’s one water, one ocean.”Samantha Jackson ’22, director of education for the Blackstone Valley Tourism Council

Samantha Jackson ’22, director of education for the Blackstone Valley Tourism Council and Captain Joe Walkden, M.S. ’98, on the Blackstone Valley Explorer Riverboat.

One Water

Researchers and advocates, whether talking about rivers, streams, harbors, or the ocean—all emphasize a critical point: All water is connected.

“Water is a big repository,” says Oyanedel-Craver. “Everything we use, from plastics to fertilizers, shows up in the water—including medicines. I learned from a mentor that everyone is downstream, and there is only one water.”

“Rhode Island is called the Ocean State,” says Herron, “but we have to remember that anything that enters the rivers winds up in the ocean.”

Jackson makes that point when talking about the 19 dams along the Blackstone River. “They can’t be taken down because that would release poisonous sediment containing a variety of toxins into the river, and then, eventually, into the bay.”

“People should stop thinking, ‘seacoast, oceans, rivers, streams,’” says Jackson. “It’s one water, one ocean.”

Photos: Nora Lewis; Issac White

Working for Rhode Island Rivers

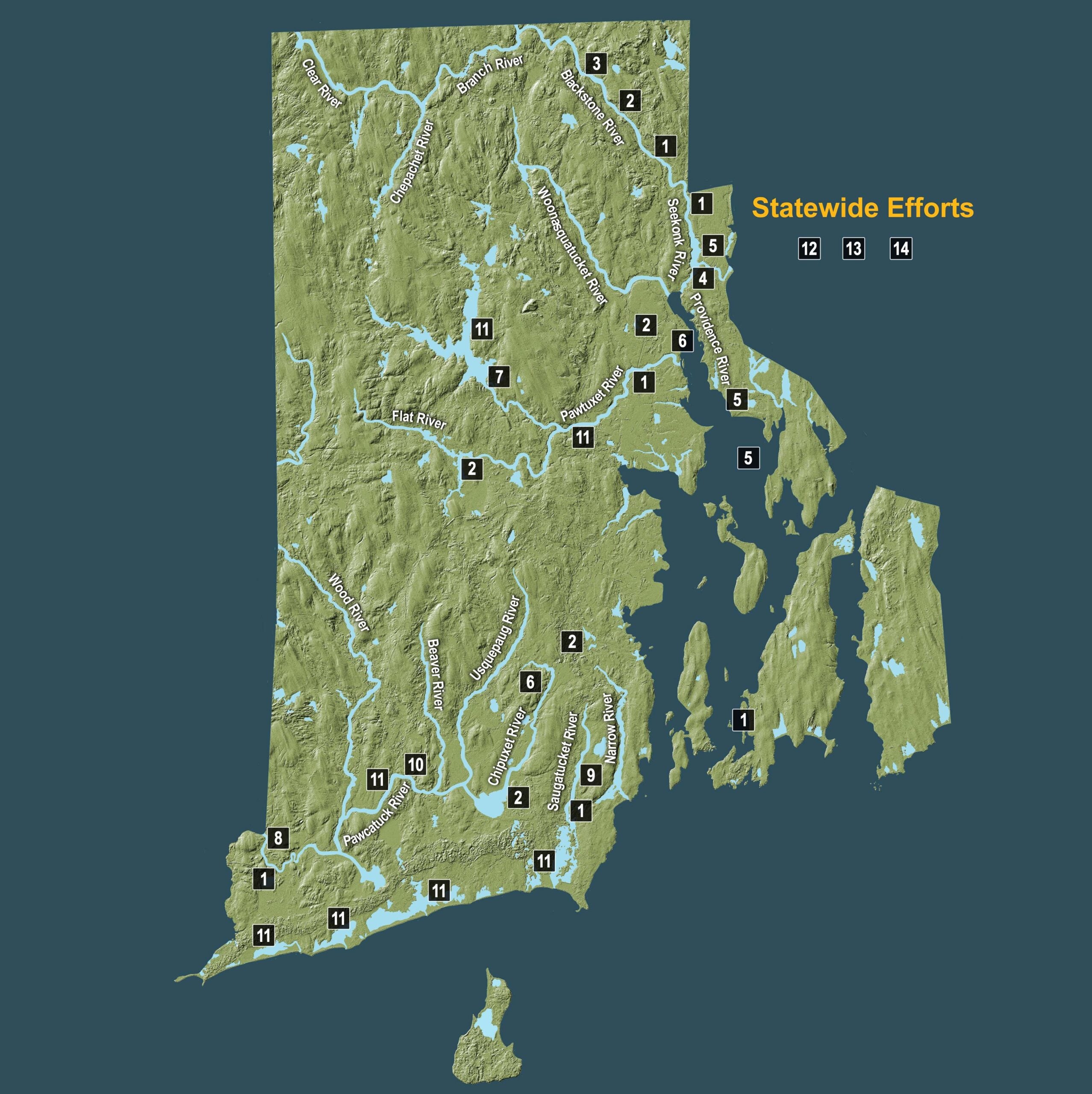

URI researchers are a force for good when it comes to Rhode Island’s rivers—from the Blackstone to the Saugatucket.

–Dave Lavallee ’79, M.P.A. ’87

On The Map

Click on the numbers on the map to learn about the work URI faculty are doing on Rhode Island rivers.

1.

Where

Blackstone, Pawtuxet, Pawcatuck, Saugatucket, and Seekonk rivers; Newport Harbor

What

Long-term testing for nutrients (phosphorus, nitrogen) and heavy metals (mercury, lead). Collaboration with EPA on a 2001 report on Blackstone River water quality improvements.

Who

Raymond Wright, emeritus dean, College of Engineering

Impact

Results used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management to set water quality/pollution standards.

2.

Where

Blackstone River, Roger Williams Park, Flat River Reservoir, Worden Pond, Belleville Pond, and statewide

What

The first systematic baseline assessment of plastic waste in the state’s freshwater systems, including a focused study on the Blackstone River.

Who

Sarah Davis, Ph.D student; Andrew Davies, professor of biological sciences and oceanography; Coleen Suckling, assistant professor of fisheries, animal and veterinary science; Elizabeth Herron ’88, M.A.’ 04, director of URI’s Watershed Watch.

Impact

This survey will facilitate research and management to reduce plastic waste in watersheds and drinking water.

3.

Where

Blackstone River

What

A student-led project produced a report on improving river access for the city of Woonsocket.

Who

Will Green, professor emeritus of landscape architecture

Impact

The report supports active redevelopment efforts aiming to improve access to and from the river at city parks including Thundermist Falls and River Island Park.

4.

Where

Seekonk River and Henderson Bridge Corridor

What

Student-led projects on natural restoration and filter systems for land along the Seekonk River in East Providence and Providence, as well as alternative river crossings, and improved river access.

Who

Will Green, professor emeritus of landscape architecture

Impact

The students and the project’s clients—the Seekonk Riverbank Revitalization Alliance and the planning departments in Providence and East Providence—received the 2020 student award from the American Planning Association’s Rhode Island chapter.

5.

Where

Providence and Seekonk rivers, Upper Narragansett Bay

What

River modeling and data collection showing how nutrient levels, rainfall, water temperature, and flow impact estuarine ecosystems. Assessing impacts of natural versus human nutrient inputs, and remediation successes.

Who

Chris Kincaid, professor of oceanography

Impact

Data gathered since 1998 has informed Narragansett Bay Commission decisions regarding sewage treatment infrastructure and processes.

6.

Where

Chipuxet River, Field’s Point Wastewater Treatment Facility (Providence)

What

Assessing microplastics and microfiber contamination in small water utilities and private wells.

Who

Vinka Oyanedel-Craver, associate dean of research and professor of civil and environmental engineering

Impact

Determined the baseline levels of microplastics contamination in Field’s Point Wastewater Treatment plant and URI Kingston Campus water wells.

7.

Where

Scituate Reservoir (Gainer Dam)

What

Assessing the dam’s ability to withstand seismic activity.

Who

Aaron Bradshaw, professor of civil and environmental engineering

Impact

The Scituate Reservoir supplies drinking water to 60% of the state. Bradshaw’s analysis determined the dam can withstand earthquakes at the levels most likely in the region.

8.

Where

Pawcatuck River (Potter Hill Dam)

What

Researching the potential hydrogeologic impacts of removing Potter Hill Dam, the last dam left intact on the Pawcatuck River.

Who

Soni Pradhanang, associate professor of hydrology and water quality and Thomas Boving, professor and department chair, geosciences

Impact

Potter Hill Dam is in disrepair and is a barrier to fish passage. Removing it and returning the Pawcatuck River to its natural flow could have positive environmental impacts, while a dam failure may affect properties and businesses up- and downstream. This research will look at the big picture and make recommendations for maximizing benefits and minimizing potential damages.

9.

Where

Saugatucket River

What

Student-led projects on improving river access and providing green infrastructure

Who

Will Green, professor emeritus of landscape architecture

Impact

The project led to a historic renovation of Saugatucket Park in Wakefield and continues to be used by the town for planning purposes.

10.

Where

Pawcatuck River

What

Identifying sources of PFAS and researching river dynamics from source to estuary.

Who

Rainer Lohmann, professor of oceanography

Impact

Data identified waste lagoons as a key source of PFAS that end up in the river.

11.

Where

Scituate Reservoir, Pawtuxet River watershed, Wood Pawcatuck watershed, salt ponds, and statewide

What

Developing models that predict how watersheds, rivers, and groundwater react to as flooding storm surges.

Who

Soni Pradhanang, associate professor of hydrology and water quality

Impact

Models have led to better management of the Scituate Reservoir, reduced flooding downstream, and more accurate evaluation of the impact of storm surges on groundwater wells.

12.

Where

Statewide

What

Collaboration with the URI Center for Pollution Prevention to help companies reduce and prevent river pollution from 1987–2012.

Who

Eugene Park, Ph.D. ’94, and the late Stanley Barnett, professors of chemical engineering

Impact

Resolved many pollution problems for industries like metal finishing, textiles, seafood processing, and auto repair.

13.

Where

Statewide

What

Historical and material research on antique quilts Rhode Island.

Who

Professor of textiles, fashion merchandising and design Linda Welters and Margaret Ordoñez (emerita)

Impact

Their book, Down By the Old Mill Stream: Quilts in Rhode Island, documents their research and details about R.I.'s textile industry and rivers.

14.

Where

Statewide

What

Some 350 URI Watershed Watch (WW) volunteers gather water samples from 220 locations statewide, including rivers. Samples are analyzed and recorded by WW.

Who

Elizabeth Herron ’88, M.A.’ 04, director, URI Watershed Watch; student lab technicians

Impact

WW has 35 years of water-quality data, which is used to monitor conditions and trends, and is used by researcher partners to encourage sound management programs.

Map: University of Rhode Island Environmental Data Center

I ride many bike trails in SE New England and now in FL. The Lincoln-Cumberland bike trail is my favorite. It is so beautiful any time of year. I very much appreciate the cleanup efforts that have made this possible.

What a wonderful and encouraging article! So glad the waters have cleaned since the 1970s.

Excellent review of past disregard for the variety of pollutants in run off water and its impact on stream and river ecosystems!!

The Law of Conservation of Matter teaches there is no “away” to throw or wash wastes into…

Finally, this story is being told. Bravo URI for your efforts to tell it.

Good review of rivers past and present, but the idea that dams can’t be taken down due to polluted sediments is narrow minded in my opinion. Dams as they become older are a public safety hazard and their presence is an ecological disaster to anadromous and catadromous fishes which need our help on the Atlantic coast. These fishes are an integral component of our ecological food web and their continued demise threaten all manner of freshwater and marine life including but not limited to birds, fish, and mammals. Think eagles, ospreys, heron, monk, otters, bluefish, striped bass, cod, tuna, whales, and many, many others. The effect of dams on diadromous fish runs are profound and removal should always be preferred over fish ladders. Sediment removal is part of the hurdle, but dams should be removed in all cases once their initial uses are no longer needed.

Oh yeah, and what about nutrients and Little Narragansett Bay? Where’s the love for our only Wild and Scenic River watershed? The Wood-Pawcatuck Wild and Scenic Rivers Watershed. My understanding is that there is an anoxic “dead” zone in the lower river in the vicinity of Westerly. Not only that but I’ve heard that development pressures are already outpacing planned improvements to the currently overburdened wastewater treatment plant.

Yes rivers are important and URI does great work, but we are not out of the woods with regard to our natural resources and environment. Not by a long shot unfortunately.