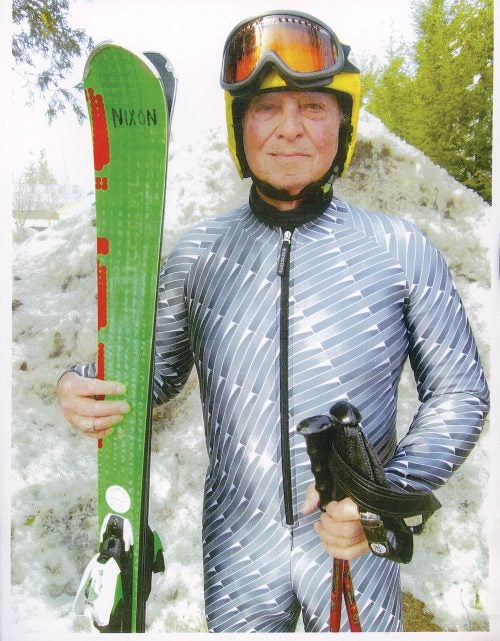

Even on a golf course, Bill Nixon ’58 knows how to take things up a notch. Consider the golf cart he customized with old Jaguar parts—from gleaming rims to leaping-cat hood ornament—to use when he hits the links with friends. It’s almost as much bling as the stockpile of gold medals—more than 300—the 89-year-old has racked up in national skiing competitions since he first started racing at age 55. He is a former president of the Warwick Country Club, but the slopes will always beckon. “I like the speed, the exhilaration of skiing,” Nixon says.

He never skied when he was younger. As a kid growing up in Cranston, he was more inclined toward pick-up baseball or hockey on Meshanticut Lake. After high school, he took a five-year apprenticeship at Brown & Sharpe, then the country’s largest manufacturer of machine tools. “You signed a contract that you would not get married, and you wouldn’t drink or smoke,” he says of the tightly run program. By the time Nixon enrolled in URI at age 23, the Korean conflict was underway. He joined the Navy Reserve, then enlisted full time. Still, he managed to finish his industrial management degree in less than three years upon returning to school—senior class president, no less. Even then, Nixon was someone who knew how to make up for missed time.

He was 30 the first time he tried skiing, invited by friends to join a ski club in North Conway, New Hampshire. He began spending much of his time there on the slopes and in a farmhouse-turned-ski-house that slept 40. “It was a good way to meet people,” says Nixon, although he couldn’t help noticing the mountain lacked a good cocktail lounge for socializing. Undeterred by lack of experience, he partnered with two ski buddies to open the Alpine Inn motel and restaurant at the base of Cranmore Mountain—a hugely popular venture that quickly became known as the “Alpine Fun Spot.” He taught himself to ski while teaching economics and machine processes at Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston. “The [lodge] took off like crazy,” says Nixon. “It got to the point where I never went skiing. I was so busy running the business.”

When he did find time to ski, he was known for his speed. After seven years he sold the lodge; he had become an impressive force on the slopes—and the president of his ski club was coaxing him to try racing. “I kept saying I was too young,” says Nixon, who figured he’d have a better chance of beating the older guys. By his mid-50’s, he gave in and trained for a season. “I started taking lessons because skiing and racing are quite different,” he says. “You don’t slide; you have to carve.” At 55, he entered his first NASTAR race (the worldwide National Standard Race program for ski racers and snowboarders, held across 100 mountains). In the 45-gate giant slalom, he beat the nine-time Rhode Island champion.

That was 300-something medals ago. “Probably more,” he admits.

Broken ribs. Broken knee, nose. Concussion. The octogenarian doesn’t get hung up on his past injuries. “You can’t think about getting hurt,” he says. “It’s just part of the game.” He focuses instead on keeping in shape (“I ride a bike, go to the gym, things like that”) and mostly attributes his longevity as an athlete to genes, luck, and attitude. It’s a winning combo behind a life generally lived in high gear, from his torch-red Corvette Stingray to his house on Warwick Neck, which was featured on HGTV’s If Walls Could Talk for being the “crime castle” of Prohibition-era rum runner Carl Rettich. In recognition of his ski racing, he has earned two City Council resolutions and a recent R.I. Senate citation. In addition, the city of Warwick declared November 6, 1991, William “Bill” Nixon day, partly in honor of the ever-growing neighborhood Fourth of July parade celebration he and his wife, Madeline, have hosted for more than 25 years, a community tradition.

He sometimes wonders how far skiing would have taken him if he’d started earlier. “Most Olympic skiers start when they’re 5 years old and dedicate their life to it,” Nixon says.

“I always thought maybe if I had started at that age … you never know.” Memories of a handful of second-place finishes still dog him, especially the win he missed by four-tenths of a second on Colorado’s Winter Park Mountain in 2010 after switching out his skis for a new pair right before the race. “I was upset with myself for that,” he says.

The wins are sweeter to remember—especially that very first race, up against skiers who had been competing for decades. Some novices might never have believed they had a chance, but that isn’t how Bill Nixon became a champion.

He says, “You always think you’re going to win.”