Collection is largest in the world!

Collection is largest in the world!

KINGSTON, R.I. –January 3, 2006 — How is it that the smallest state in the union has the largest dressmaker pattern collection in the world?

The answer is Joy Emery, a professor emerita of theatre and former adjunct professor of textiles, fashion merchandising and design at the University of Rhode Island, who has a passion for preserving patterns.

The largest pattern collection in the world? “To the best of my knowledge,” responds the “retired” professor who has spent 25 years collecting and preserving dressmaker patterns. Emery believes that the Doris Stein Research Center for Costume and Textiles in Los Angeles with 7,180 patterns in its collection holds second place. By comparison, URI’s collection contains nearly 30,000 patterns as well as fashion periodicals, tailoring journals and other related artifacts dating from the 1860s.

Housed in the Special Collections Unit of the URI Library, the Commercial Pattern Archive, http://www.uri.edu/library/special_collections/COPA/index.html, is a project of Save America’s Treasures.

“Commercial patterns present a broad spectrum of everyday dress and provide a significant documentation of American culture,” she says. “Clothes on display in museums are generally high end, couture dress that were deemed worth saving. Clothes made from commercial patterns were often handed down and/or recycled into quilts or rugs.”

Preserving patterns is challenging, considering that full-scale tissue paper clothing patterns are designed to be disposable. In fact, it’s common for pattern companies to contact Emery for a pattern since they routinely destroyed their outdated patterns.

For the past dozen years, Emery and a cadre of volunteers and student workers have scanned the front and back of more than 29,200 pattern packages in the collection, which span a century –from 1868 to 1968 — into an electronic database. The result is a three-volume CD-ROM set, which can be purchased as a set or sold separately. The first CD covers 1868 to 1944, the second disc covers 1945 to 1956, and the third disc covers 1957 to 1968. The discs can be purchased for $100 each or the set for $260. A user manual is available for $15. Emery et al are currently scanning patterns from the 1970s.

Theatrical designers, clothing manufacturers, social historians, and museum curators, among others, have purchased the CDs, using the treasure-trove of information to recreate a time and place or date clothing in collections.

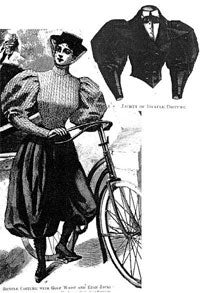

Emery is still bursting at the seams with patterns. Her latest endeavor is archiving 150 large pattern sheets that were folded into Harper’s Bazar (yes, it’s spelled correctly) Weekly from 1868 to 1903 as a promotional giveaway. These fragile, double-sided sheets have 20 to 24 patterns superimposed on each other. The patterns, defined with a complicated maze of coded lines, dashes, and stars, are designed to create fashionable garments for men, women, and children, undergarments, doll clothes, pen wipers, lampshades, and other decorative items for the Victorian household. Too large to be scanned, Emery is preserving the 30-inch by 23-inch sheets in flat storage boxes in the archive, thanks to a Rhode Island Council for the Humanities grant.

“All of these patterns are expressions of their time period and reflect the society in which they were made,” Emery says. “These early patterns, for example, come in one size, without markings or directions or yardage needed since it was assumed that all women possessed sewing skills.”

Trends can also be traced through the patterns, such as the evolution of pants for women—from bathing suits, to bicycling and other sports activities, to the influence of Hollywood’s silk pajamas.

The URI professor was inspired to collect patterns, after finding a full circle skirt pattern for a character in the University’s production of Anne of Green Gables in the her friend’s collection. The friend, Betty Williams, was a New York costumer and pioneer in dressmaker pattern research. When she died, all of her 12,000 patterns were donated to URI, propelling the University into pattern history.