KINGSTON, R.I. – January 3, 2013 – University of Rhode Island student Keri Dyer fought through thickets of brush and briers and through knee-deep wetlands to study the habitat needs of New England cottontails, but never once in her project did she actually see the subject of her research. She didn’t expect to.

KINGSTON, R.I. – January 3, 2013 – University of Rhode Island student Keri Dyer fought through thickets of brush and briers and through knee-deep wetlands to study the habitat needs of New England cottontails, but never once in her project did she actually see the subject of her research. She didn’t expect to.

“Available habitat for New England cottontails in southern New England has declined by 86 percent since the 1960s,” said Dyer, a resident of Smithfield studying wildlife and conservation biology at URI. “They like new growth forests, but due to fragmentation and maturing of habitat, there is minimal habitat available so populations are very very low.”

A 2010-11 survey of the region’s native rabbit found just one New England cottontail in all of Rhode Island, despite having more than 100 people searching for them.

Efforts to protect the cottontails have focused on finding and identifying their preferred habitat – shrubby areas with scattered small trees.

“The rabbits need a certain amount of shrub coverage to thrive,” she explained. “The average seemed to be about 60 percent shrub coverage, and just about the only places that have that coverage are new growth forests,” like abandoned farm fields or areas where forests had been cut down several years ago.

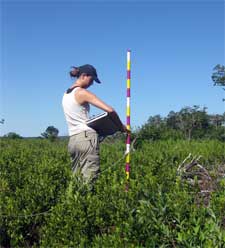

Working with URI graduate student Amy Gottfried and Professor Tom Husband, Dyer visited 78 such locations throughout Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut last summer. At each site, she laid out a 50-meter grid, counted and measured woody shrubs, assessed herbaceous cover, and calculated how much area was covered by trees.

Working with URI graduate student Amy Gottfried and Professor Tom Husband, Dyer visited 78 such locations throughout Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut last summer. At each site, she laid out a 50-meter grid, counted and measured woody shrubs, assessed herbaceous cover, and calculated how much area was covered by trees.

According to Dyer, protecting habitat is crucial to restoring healthy populations of New England cottontails, but scientists must also cope with the non-native Eastern cottontail, which was introduced to the area in the early 1900s and seems to be outcompeting the native rabbit for resources.

“The two species look very similar, they have the same range, and the introduced species seems to be able to live in areas that are more developed and closer to people,” she said. “New England cottontails hide in the brush to avoid predators most of the day and only come out in the early morning and at dusk.”

Dyer’s research was conducted as part of the URI Coastal Fellows Program, a unique initiative designed to involve undergraduate students in addressing current environmental problems. Now in its 17th year, it is based at URI’s College of the Environment and Life Sciences. Students are paired with a mentor and research staff to help them gain skills relevant to their academic major and future occupations.

“I really liked learning field techniques, and I loved working outside, even when it was hot and raining,” Dyer said.

The cottontail project wasn’t Dyer’s first foray into wildlife research. In 2011 she analyzed the health of local salt marshes using a small baitfish as an indicator species. The project involved catching mummichogs and dissecting them in a lab.

“Mummichogs are hardy, so the health of the mummichog tells us about the health of the marsh,” said Dyer.

The URI student is already looking forward to conducting another research project next summer, perhaps even in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“I’ll work on whatever project they have and do whatever needs to be done. Just give me some bug spray,” she said.

The experience she gained from her first two research projects has convinced Dyer that a career in environmental research is in her future.

“I definitely want to do research with wildlife, and a career with Fish and Wildlife would be ideal,” she concluded. “I would especially like to work with birds of prey. But for now, I’ll let the wind take me and find a good place for me.”

Photo submitted by Keri Dyer