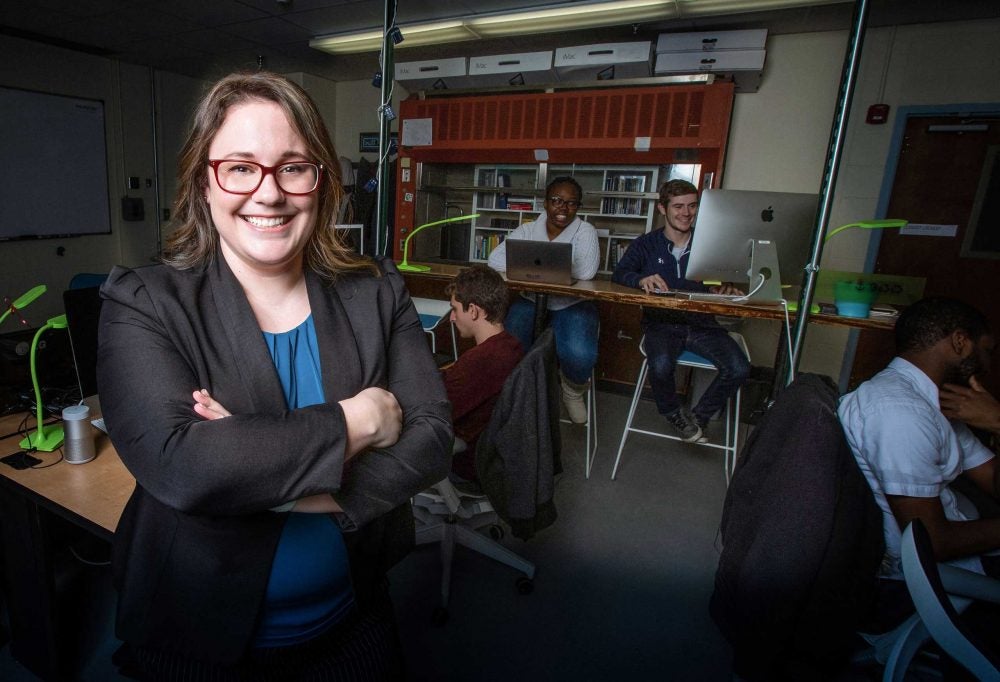

Professor Gretchen Macht and student researchers in the Sustainable Innovative Solutions Lab.

Assistant Professor of Engineering Gretchen Macht will tell you, you can throw all the money in the world at a piece of technology, but if people don’t use it, it’s pretty much worthless.

A member of the College of Engineering’s Mechanical, Industrial and Systems Engineering faculty—and a teamwork enthusiast—Macht is director of URI’s Sustainable Innovative Solutions (SIS) Lab which studies how people engage with sustainability by way of technology.

Research and experience have taught Macht that the key to building a sustainable future is to create systems informed by the human factor, which, at its core, is how we think and work.

“Systems are anything people interact with—a school is a system in that you have a building and staff and faculty working to provide students knowledge,” Macht says. “The economy is a system. Teams are systems.”

Macht and her team of seven undergraduate and nine graduate researchers apply human systems engineering and ergonomics to global-scale sustainability issues concerning solar energy, electric cars, voting systems, team dynamics, and breast-pump technology. SIS Lab researchers study the ways people interact with the systems and technologies that drive efforts in sustainability.

“Sustainability is a systems problem, and it’s a human problem,” Macht says.

The SIS Lab

The lab where Macht’s team works is its own model of sustainability—with ergonomically designed chairs, carpet squares that can be deconstructed and repurposed, and work stations made from repurposed, naturally fallen lumber. There is a bank of clocks set to different time zones and a map with pushpins marking the homes of every researcher who’s worked there. It’s a friendly, inviting space—which is a very good thing because Macht’s team spends quite a bit of time there.

The study of big issues takes a serious time commitment. Not that there’s any complaining from the team—who are there after hours on the Friday before spring break. Graduate student James Houghton doesn’t mind. “The more I can give to Dr. Macht, the more she gives to me,” Houghton says. “She motivates us to want to do good work and bring it back to her.”

“They do it all,” Macht volleys back.

But what do they do exactly? Take solar power, for instance. There are nearly two million solar energy systems installed across the country, and that number is expected to double in the next four years. Macht and her team study how embracing solar energy might influence human behavior and consider what is necessary to ensure its mass adoption.

‘We measure what we value’

“A significant barrier to entry with solar is that people can’t afford it or do not own their roofs, so how are socioeconomic strata and income influencing social behavior?” Macht says. “How do we measure the ways that people react to solar panels? How can we understand the community level of solar?

“We measure what we value, and we value what we measure. So, how can we start creating a holistic understanding of that in solar energy?” Macht says.

Sometimes seeking answers requires the investment of more than time and thinking. One SIS research team is investigating issues around electric vehicles: people’s charging and driving behaviors, the relationship of where public charging stations should be located, and the individual ergonomics of eco-driving, for example. Macht has enlisted more than 75 people to drive her electric car to better understand how people drive them.

“We know there are aggressive and cautious drivers,” Macht says. “What does that mean in terms of the energy they’re consuming? What does that mean for infrastructure models? The more questions asked, the better the integration might be between system, community, and individuals.

“I view sustainability as a holistic system, ” she adds. “It’s more than just environmental—it’s economical and social, and they all must be aligned.”