The URI College of Pharmacy and the Heber W. Youngken Jr. Medicinal Garden work hand in hand, training students to look for new medical uses for plants.

You may know that echinacea wards off colds, or that garlic reduces blood pressure. But you might not know that here at URI’s College of Pharmacy, the medicinal garden and greenhouse help students understand the plant/medicine connection and how to look for new medicinal uses. The College of Pharmacy’s founding dean, Heber W. Youngken Jr., planted the original garden in 1957 near Fogarty Hall. In 2013, the garden was expanded and moved next to Avedisian Hall with glass frieze panels and a living art installation.

Today it’s one of the largest and most established in the region, with more than 200 medicinal plants that help treat diseases ranging from anxiety to heart disease to cancer.

“URI is one of only a handful of colleges of pharmacy affiliated with a medicinal garden in the U.S.,” says Navindra Seeram, a professor in the Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “We are well-known for our pharmacognosy leadership. In fact, the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy is planning to start a medicinal garden and they’re looking to us for guidance.”

The garden is a unique resource that is an important part of URI’s prominence in natural products research as well as a resource for students and faculty.

The garden is a unique resource that is an important part of URI’s prominence in natural products research as well as a resource for students and faculty.

“We can’t be a leader unless our students are well-versed in medicinal plants and the molecules they possess; the garden helps us in our teaching and training. It also brings prestige to our college and our research. When we produce and publish research, it demonstrates the quality of our natural products group’s work, and we’re very proud of that,” says David Rowley, chair of the Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

The garden is used in pharmacy classes such as Medicinal Plants (BPS 533) and Herbal Medicines and Functional Food (BPS 203), as well as for a graduate course on natural products. It also serves as a home base for the Pharmacognosy Club, which is open to students from all disciplines who are interested in medicinal plants. Rowley calls the garden an organic continuum of the college–a place to meet colleagues, eat lunch, host functions, or just sit, think, and de-stress.

Take a tour with garden coordinator Elizabeth Leibovitz and you’ll find her enthusiasm is contagious as she points out different plant species and their uses: Goji berry to treat inflammation, cinnamon to settle gastrointestinal upset, and foxglove, which is used to make the heart medicine digitalis.

Leibovitz explains that plants are used in three levels of medicine, the first being nutraceuticals, foods you eat for their benefits beyond basic nutrition, like pomegranate. Second is herbs for self care, including dietary supplements and home remedies, like ginger taken for nausea. Third, there are more clinical uses for plants, where are compounds are dried and isolated. She points out a pretty purple-flowered shrub. “The Madagascar periwinkle, for example, is very popular in landscape use, but it contains vincristine and vinblastine, two of the most toxic substances on Earth, which are used in chemotherapy.”

Seventy percent of FDA-approved drugs come from natural sources or have been inspired by natural products. That’s where Matthew Bertin, assistant professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences, comes in. His class, Techniques in Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Biology (BPS 451), focuses on the medicinal plants in the garden, which Liebovitz collects and dries. Each student lab group chooses a plant and works with it for nearly the entire semester. Because the garden is on campus, students can analyze the raw plant rather than relying on someone else’s data.

Students use high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and mass spectrometry to identify plant compounds and their properties. It’s the same high-tech analytical equipment you’d find in an industrial lab.

“It’s a really unique job, giving students a living platform for learning.”

–Elizabeth Leibovitz

“The industry needs folks who can perform analytical techniques. You may find a product from a plant, but there’s an analytical procedure you have to conduct to figure out elements such as potency and effectiveness, or if it’s not perfect, how to optimize it. The garden helps bring this learning to life. Having hands-on knowledge of these systems helps hone students’ skills and makes them more marketable,” says Bertin.

James Lotti ’19 worked with Bertin to analyze the chemical components of the Korean balloon flower, Platycodon grandiflorus. “We performed the analytical techniques and ran an assay for antioxidant bioactivity on the various fractions of the extract,” says Lotti. “We then compiled the results from these techniques into a publication-style lab report. The experience taught me a lot about the potential pharmaceuticals from natural products.”

Students rely on the garden to learn about traditional and modern plant medicines.

Students in the medicinal plants class rely on the garden to learn about traditional and modern natural plant medicines, as well as other organisms that potentially contain bioactive components with therapeutic applications. Kelly McManus ’19 says she learned more about plant uses through an herbal recipe project in that class.

“We took plants from the garden and created things that can be taken for a chosen indication,” she says. “I made gummy bears with elderberry and other supporting herbs to boost the immune system and prevent or treat the common cold. We were able to see the end product of many herbs used in different ways for medicinal purposes.” Other projects in the class yielded lip balms, teas, face masks, tinctures, and more.

Beyond the classroom, there is a huge appetite for nutraceuticals and herbal supplements. URI students well-versed in plant analysis can travel many different career paths, says Bertin. “In addition to graduate school, they could work at Merck or Pfizer, or in nutraceuticals, or even in the craft beer industry, which uses hops and engages with chemistry and plants. Having the garden here helps us facilitate those opportunities for students.”

At the graduate level, students and faculty are taking research several steps further, and Seeram’s work with maple compounds has put URI at the forefront of pharmacognosy.

“We are undoubtedly the world’s leader in maple research.We have been funded by the USDA twice, and that speaks to our ability to lead research on this unique botanical.”

–Navindra Seeram

“When you look at other botanicals, everyone is researching them. But the red and sugar maples only grow in the northeastern U.S. and Canada, and URI is the first to study their bioactive compounds. We are undoubtedly the world’s leader in maple research based on the amount of peer-reviewed publications we have on the different species of maple and their derived food products. We have been funded by the USDA twice, and that speaks to our ability to lead research on this unique botanical,” Seeram explains.

What’s next? Future plans for the garden include a Native American plant collection, where Leibovitz hopes to establish a local medicinal plant collection based on plants the Narragansetts and other local tribes used as medicine.

Good for What Ails You

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus)

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus)

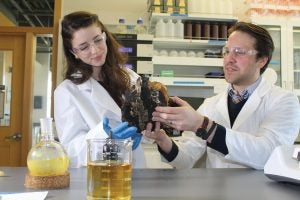

Graduate student Riley Kirk is studying this fungus for its antidiabetic properties, which prevent the production of advanced glycation end products that are partially responsible for diabetes’ negative effects. It has been used as a tea and tincture for at least 400 years. Since it only reproduces in the wild every 30 years, overharvesting has become a pressing issue, and Kirk is currently studying how to reproduce the fruiting body reliably in the laboratory.

Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

Traditionally, its dried fruit, rind, and fruit pulp were used as remedies for upset stomachs and diarrhea. More recently, Professor Seeram’s extensive research found possible positive effects on the brain, improving functions such as memory and cognition. He discovered how pomegranate’s polyphenols were biotransformed by gut microflora to produce urolithins, potentially active compounds for treating Alzheimer’s, thus opening the door to a new line of research.

Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

This plant has several benefits: It is antibiotic, astringent, and antifungal, as well as hypotensive, which means that it lowers blood pressure. Interestingly, it is now being used as an herbal antibiotic for Lyme disease, another tool in medicine’s arsenal as strains of the disease become antibiotic-resistant. It also has a range of traditional uses for sores, burns, ringworm, and acne.

Red Maple (Acer rubrum) and Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum)

Red Maple (Acer rubrum) and Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum)

In leading-edge research, Professor Seeram and his team have isolated more than 67 compounds in maple sap and syrup. That includes Quebecol, a polyphenol that could have anti-inflammatory properties and could offer new treatments for diabetes and Alzheimer’s. They’ve also isolated compounds in maple leaves that might prevent wrinkles and licensed it to Verdure Sciences for possible cosmetic uses.

Turmeric (Curcuma longa)

Turmeric (Curcuma longa)

In the same plant family as ginger, turmeric has been used extensively in Ayurvedic medicine (a traditional healing system from India) for indigestion and anti-inflammatory conditions. Today it is primarily used to help prevent colds and to prevent inflammation in the body. It also helps reduce bloating and stimulates bile flow.

Green Tea (Camellia sinensis)

Green Tea (Camellia sinensis)

An extract from green tea was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2006 as the first prescription botanical drug. Named Veregen, the drug’s active ingredient is Polyphenon E, a proprietary mixture of phytochemicals extracted from green tea in water. It is used to treat genital warts from HPV. Green tea also has many uses in traditional Chinese medicine for weight loss, skin ailments, and as a diuretic.

– Diane M. Sterrett