How Brad Wetherbee Became URI’s Shark Guy

Brad Wetherbee has studied shark evolution, migration patterns, and habitats for more than 30 years. He is also a dedicated teacher who creates opportunities for his students to learn about sharks through fieldwork and hands-on learning.

By Meredith Haas ’07, M.O. ’22

Ten years from now, students in Professor Brad Wetherbee’s class will remember they swam with whale sharks. Not the research methods or their notes. They’ll remember they swam with the largest shark and the largest of any fish alive today, he says.

“Swimming with whale sharks is on the bucket list for a lot of people. This class is probably the only place where you can experience that as a student,” Wetherbee says, discussing an August 2022 trip to Mexico he led with 12 undergraduates from the University of Rhode Island as part of a field research methods class he teaches. “Whale sharks are huge plankton/filter feeders, so they’re not dangerous, but you can’t catch them and handle them on a boat. So, we go to Mexico, where we can observe and study them in their habitat.”

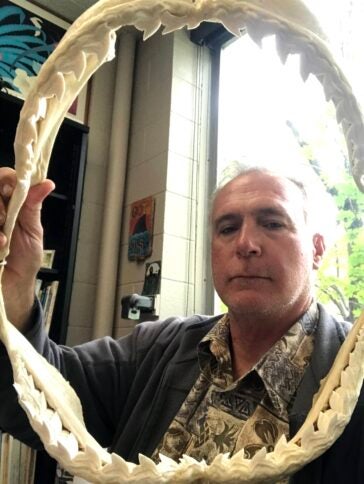

Wetherbee, an assistant professor of biology at URI, is known as the “shark guy” around campus—and around the state of Rhode Island. He has spent more than three decades studying shark evolution, migration patterns, and habitats, with a focus on conservation. His office is a testament to that research: Upon entry, you are greeted by an 18-inch tiger shark jaw with perfectly notched, serrated teeth. This is just one of a dozen specimens among an orchestrated chaos of memorabilia from his field research and travels. His office also features pictures of family, vast collections of books, and stacks upon stacks of papers—some that need to be graded and some—current articles on shark research—he means to read.

Wetherbee favors Hawaiian shirts and wears an expression best described as inscrutable. But get him talking about sharks and its clear he loves his work.

“There are a lot of students who say, ‘I just want to do what you do right now,’ and I say ‘Yeah, well, I spent a lot of time getting to where I am now.’”

A self-described quiet and shy kid, Wetherbee, now 63, says his journey to becoming a beloved professor and respected shark expert wasn’t one of pure intent. In fact, growing up, he didn’t have any particular interest in sharks. Rather, his journey was a series of forked roads.

“My dad used to quote Yogi Berra: ‘When you come to a fork in the road, take it,’” Wetherbee says, explaining that it’s not about which direction you choose as long you have a direction. “You’ve got to go somewhere.”

Wetherbee’s father was a fish biologist for the state of Oregon and would often take him into the field, where he learned about the fish living in the rivers and alpine lakes.

“I liked going to work with him a lot when I was a little kid,” Wetherbee says. “We’d drive up to the mountains, to these high lakes, and hike and go snorkeling.”

Although instilled with an appreciation for wildlife and nature, and more knowledge about biology than most people his age, Wetherbee was like many first-year college students who don’t know what they want to do or who they want to be.

“After a year, I thought, ‘What do I like more than biology? Probably nothing,’” he says. By the time he graduated, he realized he wanted to continue his studies because he had only scratched the surface. “I got to the point where I kind of understood things, but not that well. I realized there was way more to learn, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

Both of his parents and many of his friends went to Oregon State University, where Wetherbee says he probably would’ve gone to study birds. Instead, he took a year off traveling. While visiting a friend in Hawaii, he discovered Gunnar Thorson’s Life in the Sea. Published in 1971, Thorson used vivid illustrations to provide a broad overview of marine life.

“There wasn’t much in the field of marine biology back then,” explains Wetherbee as he pulls out a copy of Thorson’s book from his bookshelf. “I thought that if I could sit there and read this book for pleasure, then of course marine biology was what I was going to do.”

His revelation would ultimately land him in Florida at the University of Miami. All he knew when he got there was that he wanted to work with vertebrates. He talked to several professors studying fish behavior and turtle physiology, but it wasn’t until he talked to “this guy” studying sharks that his interest was really piqued.

“He said, ‘I’ve got so many things for you to do. You’re going to be out in the middle of the night tracking and catching sharks in a boat.’ He tried to make it sound like it was hard, but it seemed very exciting,’” Wetherbee says, adding that he was also intimidated. “I thought, ‘This guy is in National Geographic. I’m not going to be able to work with him.’”

“That guy” was Samuel Gruber, a world-renowned shark biologist and founder of the American Elasmobranch Society—the world’s largest association of shark and ray scientists. Under Gruber’s mentorship, Wetherbee took his first steps into shark research.

“I liked it right away, and I realized there was a lot less known about sharks than most other fish,” says Wetherbee, explaining that the knowledge gap existed in part because sharks didn’t hold any monetary value and were hard to study. “There was a huge black hole of things people didn’t know about sharks. I found that attractive because I thought I could work on this stuff my entire life and never run out of things to do.”

At first, he wasn’t sure if he was doing a good job or whether he’d be a good scientist. He recalls another graduate student asking him a bunch of questions about sharks that he didn’t have the answers for. “I realized this person, who studied coral or something, knew more about sharks than I did. And I didn’t like that. So, I made it a priority to read everything I could. I developed somewhat of an encyclopedic knowledge about sharks,” he says with a wry smile, pointing to one of the stacks of research papers on his desk. “I don’t have as much time now to go through all of them.”

The knowledge he amassed helped to build his confidence throughout graduate school. He found that despite his naturally shy and quiet nature, he was good at talking in front of people.

“Before, people would have thought I’d be the last person to get up in front of 300 students and give a lecture because I was very quiet,” Wetherbee says. “But part of research is communicating your findings. I wasn’t necessarily that good, but I talked rather than just reciting memorized information. So, I realized I could do research and I could teach. That’s how I decided I wanted to go get a Ph.D.”

Wetherbee would soon find himself enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Hawaii studying deep-sea sharks. To obtain samples of sharks to study, he worked as a technician on a five-week orange roughy trawl off the coast of New Zealand that would often catch deep-sea species as bycatch. When he was done with his work for the day, he would spend his nights studying the physiology of anything found in the nets.

“I didn’t know much about deep-sea sharks, but one of the most interesting things I learned during that experience was that they’re neutrally buoyant. Most sharks are 5% heavier than water, so if they don’t swim, they’ll sink. But, because deep-sea sharks have these large livers with a lot of low-density oil, they float and barely have to swim, so they can conserve energy,” he explains.

Wetherbee also worked as a research assistant at the University of Hawaii, tracking fish and baby hammerhead sharks with acoustic transmitters. That led to his participation on a team tracking tiger sharks in response to the state’s call for a shark culling after Hawaii’s first fatal attack in 33 years. The team’s efforts showed the vast distance tiger sharks travel, quelling any belief that a cull would be effective in killing the shark responsible for the attack.

“It was like a scene out of Jaws. They could go out and kill a shark but the likelihood of it being the culprit was very low,” says Wetherbee, noting that this experience changed the focus of his career. “I became hooked on that area of research because it could make a positive contribution towards wise management of the population.”

He brought this interest to Rhode Island as a postdoc at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Narragansett Laboratory.

“I guess it’s a prestigious postdoc,” he says with a shrug. “But they wanted me to work with dead sharks people caught in fishing tournaments. I said I wanted to track sharks instead, so I found funding to track sandbar sharks in Delaware Bay. It was exactly what I wanted to do.”

This eventually led to his work with the Guy Harvey Research Institute at Nova Southeastern University, where he studied and tracked the movements of North Atlantic shortfin mako sharks, which have been on the verge of collapse due to longline fisheries targeting blue sharks and swordfish, according to a Pew Research Center report.

“His work under Guy Harvey [produced] a really critical and large spatial data set of shark distributions,” says Eric Schneider, a marine biologist for Rhode Island’s Department of Environmental Management, who worked with Wetherbee to better understand where mako sharks spend most of their time and where they are most vulnerable. “Over the years, colleagues would say, ‘You should reach out to Brad. He’s a good scientist. You should see if he wants to partner with you.’”

Their work helped fisheries manage mako populations and led to changes in fishing regulations for the species.

Now known for tracking and studying the movement patterns of mako sharks, Wetherbee has been in Rhode Island 22 years, teaching at URI for almost as long and bringing experiential opportunities to high school and college students interested in learning about sharks.

“I really like both research and teaching. I wouldn’t want to do just one,” Wetherbee says, noting that sometimes the emphasis on research can eclipse the value of teaching. “It’s a noble profession to educate. A lot of students want to learn, and I like interacting with them.”

In addition to offering a weeklong summer shark camp for high school students, Wetherbee leads directed field research courses to give his undergraduate and graduate students opportunities to learn outside the classroom.

“Some of them have never been on the ocean or on a boat,” he says. One, Colby Kresge ’21, “had never been out of the country, and last summer we went to the Cayman Islands, Mexico, Tasmania, and South Africa. It expanded his world 300%.”

“Fieldwork was an important part for me in considering graduate school,” says Kresge, now a graduate student studying with Wetherbee. “The other part was that Dr. Wetherbee wanted to take a chance on me. Before then, I hadn’t felt seen in school and I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to do. I quickly took a liking to his research and to the opportunities he provided for students. We got to handle and release these beautiful mako and blue sharks. As an inexperienced fisher and marine studies student, I was fascinated.”

Seeing the students change from these experiences is why Wetherbee says he puts in the effort he does. “I do it because if I was in that situation, I would want someone to give me an opportunity. Sometimes it sparks an interest, and they go study sharks. Or they go do something else. But it’s helping them take the fork in the road, and I like that more than anything else.”

And maybe they’ll remember how they got to swim with whale sharks, too.

Great article on professor Brad Wetherbee! This is the exact kind of teacher we need to get students excited about working to understand sharks and the reason they are critically important to the health of our failing oceans. I am truly gratified to know that there are individuals like Brad Wetherbee teaching such important skills to our young scientists.

Thank you for providing such a rich, inspiring and informative magazine this week from URI. Makes me very proud to be an alumni from there.

Wonderful article.

Really well written article. Helps fill my knowledge gap!

Grateful alumni. Ira lew

Really well written and inspiring article for anyone, student or just a marine fan, about someone who took his own fork in the road.

Another example of the talented faculty at URI and dedication to teaching and research. What an inspiring story – both personal and professional. Job well done, Dr. Wetherbee.