KINGSTON, R.I. – Nov. 12, 2019 – University of Rhode Island biology major Devyn Barraza knows the problems pollutants have caused in Narragansett Bay – toxic algae blooms that have killed fish, runoff that has closed beaches – and the crucial need for water monitoring.

Last summer, Barraza ’20 got a chance to play a role in a program that will lead to better monitoring of the bay as a recipient of the University’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF).

Her research is part of a Rhode Island Consortium for Coastal Ecology Assessment Innovation & Modeling (RI C-AIM) program that is developing microfluidic sensors that will be stationed in the bay. Barraza is working on a team – led by Engineering Professor Vinka Oyanedel-Craver and doctoral candidate Kayla Kurtz – that is developing methods to prevent biofilm from fouling those sensors. A naturally forming collection of microorganisms, biofilm is one of the biggest challenges to long-term water monitoring.

“Biofilm is like a layer of living film. Plaque on your teeth is a biofilm,” says Barraza, of Plainville Massachusetts. “The importance of the work is that it ties into the larger picture of Narragansett Bay restoration and monitoring. Also, there’s been little research on biofilm in this region, so studying it can provide novel data and information for many fields, such as industrial, medical, and commercial.”

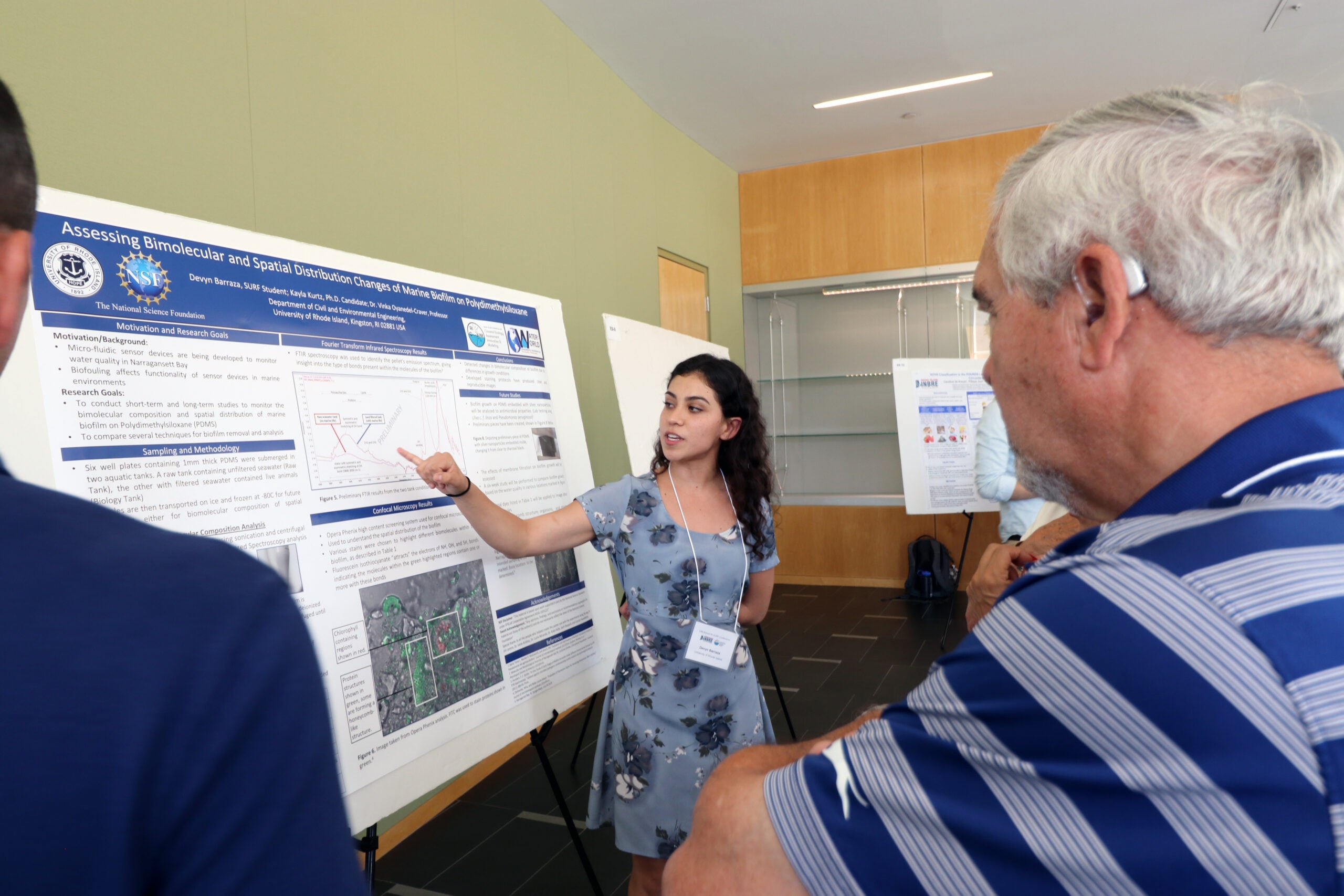

Barraza presented her research at the recent URI’s 2019 Showcase of Undergraduate Research, Scholarly, and Creative Works, and took top honors for her poster in the STEM category. She also represented the SURF program and presented her poster at the annual National Science Foundation Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research conference in Columbia, South Carolina.

Microorganisms weren’t Barraza’s primary focus when she first came to URI. A biological sciences major, she had planned on attending medical school after graduation. But during her sophomore year, she got her first glimpse at the importance of marine microorganisms in the biology class The Invisible Living Ocean, taught by Professors Tatiana Rynearson and Chris Lane.

“The class was very detailed about marine microorganisms – bacteria, fungi, phytoplankton – and the ocean in general,” she says. “How these systems work together and the important role these invisible creatures play. I was learning a lot of interesting things, and it got me intrigued in the whole field.”

Barraza switched her major to biology, added classes in marine biology and microbiology, and pursued a minor in writing and rhetoric, hoping to combine interests in communications and research. “I originally was thinking I wanted to focus on helping people, so I thought I’d be a doctor,” she says. “Then I started thinking I could do the most help by helping the environment that we all live in.”

Last spring, she took part in the URI Graduate School of Oceanography’s long-running plankton survey, which has been collecting weekly samples from Narragansett Bay since the 1950s. Another student on the plankton survey told Barraza about an opportunity to work over the summer in the Water for the World engineering lab, taking part in biofilm research. She jumped at the chance.

“The knowledge I have gained from this program is irreplaceable and I have loved everything about it,” says Barraza. “It has encouraged and solidified my passion for research, and it has allowed me to take all the information I’ve learned the past three years and apply it to real-life experimental investigation techniques and protocol development.”

Biofouling caused by biofilm is a wide-scale problem, says Kurtz, Barraza’s SURF mentor and a doctoral candidate in civil and environmental engineering. With advancements in technology, water sensors, such as those being developed by C-AIM, remain in the water for long periods and are more susceptible to biofouling that can cause faulty readings and other challenges, Kurtz says. (URI’s team is collaborating on the research with scientists at Bryant and Salve Regina universities.)

To come up with a strategy to prevent biofouling, the team’s research last summer focused on understanding the biomolecular composition and spatial distribution of biofilm as it formed on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a material similar to that being considered for use in the microfluidic sensors. For testing, biofilm was grown on six, 1mm-thick PDMS plates that were submerged in two tank environments – an unfiltered seawater tank and a tank with filtered seawater and marine life. Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, changes were detected in the molecular composition of the biofilm due to the different tank environments. Also, spatial distribution of the biofilm was inspected using dyes to stain molecules in the biofilm, such as proteins and lipids.

“We’ve been able to start determining what is in the biofilm,” says Barraza. “The end goal would be to come up with a way to prevent it from forming. That would be the best, but we’re uncertain if that is possible. So, we’re looking more at ways to reduce biofilm formation, maintain the sensors or find a solution that can quickly remove the biofilm.”

Barraza is the first biology undergraduate to work on the project, and Kurtz says she has brought a different perspective to the research, opening avenues for collaboration and innovation. “It’s been great having her bring her fundamental biology experience to the table,” Kurtz says. “It’s also great to have someone who loves to work in the lab. I sometimes get updates from her at 10 o’clock on Friday nights. She’s just very passionate about the work.”

As the research progresses, silver and gold nanoparticles will be studied to test their effect on preventing growth of the biofilm. Researchers will also compare biofilm growth in different parts of Narragansett Bay, says Barraza, who’s continuing her research thanks to an extension of her fellowship.