KINGSTON, R.I. – June 29, 2020 – Five days after Jay Sciola marks his work anniversary at the University of Rhode Island, he will celebrate his birthday. He will turn 87. That’s not a misprint.

Sciola, born Antonio but known as Jay since he was a boy growing up in South Kingstown, marks 70 years as a state employee on July 1. He is the longest-serving active state worker, and he is the senior employee at URI by 19 years.

A laborer, a plumber, a mason, a carpenter, a supervisor, Sciola has done whatever has been needed around the growing Kingston Campus for nearly 70 years, longer than most who work at URI have been alive. When asked about this accomplishment, he has an unvarnished reply.

“Don’t overblow this,” he says with a half chuckle. “It was a job.”

Sciola’s been around so long he predates URI, actually. When he started in September 1950, the University was still known as Rhode Island State College. He was here before the Memorial Union, which opened in 1954, before the Frank W. Keaney Gymnasium (1953), before the College of Pharmacy (1957).

Paul M. DePace, a URI veteran of 43 years as, first, director of the Physical Plant and now director of Capital Projects, says that when he first learned how long Sciola had worked at URI, he thought it would be quite an accomplishment if he could stay at URI long enough to see Sciola retire. He’s still waiting.

“Jay was not only knowledgeable in his trade, but knowledgeable in how things worked,” says DePace. “I came to know that I could not only count on him to understand plumbing, but how to work the system to get things done.”

Sciola was 17 when he came to Rhode Island State College looking for a job in 1950. He was a strong kid growing up in the Rocky Brook section of Peace Dale, the brawn to his older brother Clemente’s brains. He was no stranger to hard work. He lugged golf bags – sometimes bigger than him – at Point Judith Country Club, and worked a job at a state beach in the summer of 1950. But beach season was over.

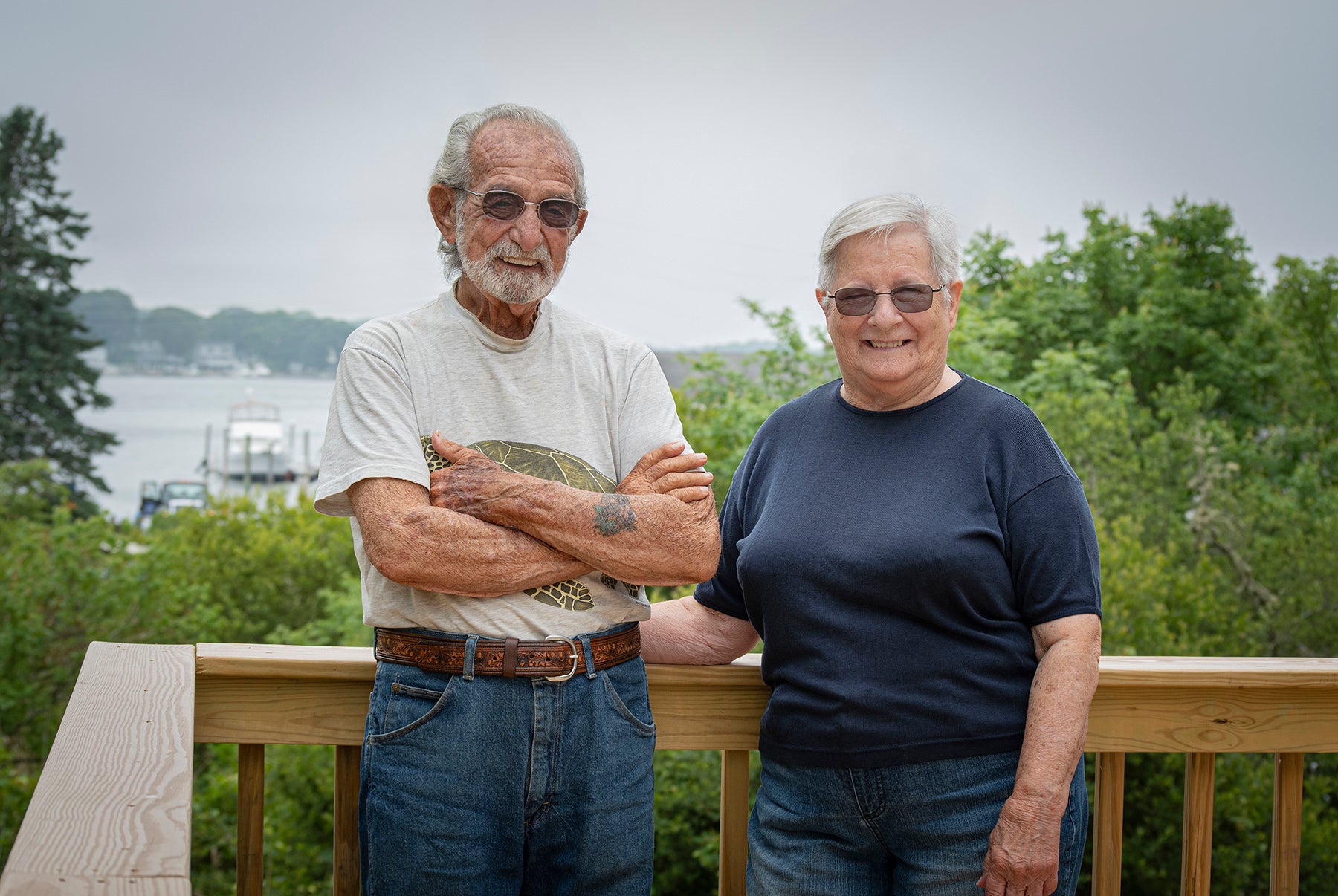

“It wasn’t a case back then of looking to work,” says Sciola, who lives in South Kingstown with his wife of 60 years, Barbara, and grandson, Julien. “You had to work to feed the family, your father needed help. I had two sisters and a brother. You didn’t have a choice. If you weren’t going to go to college, you were going to go to work. That’s why I went.”

Hired as a laborer in the plumbing shop, Sciola pretty much did everything on a maintenance crew of about 30 workers. Besides the Kingston Campus, the crew was in charge of maintenance for the Narragansett Bay Campus, East and Peckham farms, and later the W. Alton Jones Campus. The plumbing shop workers were responsible for the underground stormwater system and the sewer and water systems, but when needed, they helped the electricians, the masons, the carpenters.

“It was all physical stuff. I was the youngest guy in the crowd, so that kind of put a target on me,” he says. “Which was fine because I loved to work.”

Years later, during the Blizzard of ’78, little had changed. There were a dozen campus-wide power outages and a fire, says DePace. “In each instance, we needed people to work out and Jay was always there,” he says. “Not just in his trade, but whatever we needed. I really came to value that.”

In the early days, Sciola had a front-row seat to the birth and growth of a world-class university.

When he started, he recalls, the college was only a fraction of its size. The bulk of the campus was centered around the Quadrangle, ringed by Quinn, Ranger, Edwards, Washburn, East and Lippitt halls. To the east on Upper College Road were the fraternities. To the west was Roosevelt Hall, the only residence hall other than several Quonset huts housing female students and married servicemen. Basketball was still played in Rodman Hall, and the Union was housed in a Quonset hut.

The student body was just about 2,200 students in 1950, with most enrolled in the College of Arts and Sciences, established just two years before. The other colleges were agriculture, business administration, engineering, and home economics, which included the new School of Nursing.

“It’s really unbelievable what we had in the beginning compared to what we have now,” he says. “We have over 200 buildings we’re responsible for at four locations.”

Approaching 87, Sciola’s job in the plumbing shop may not be as strenuous as it once was. But even as he’s gotten older, he’s missed few days – until recently. With the COVID-19 pandemic and the governor’s stay-at-home orders, Sciola has been home on sick leave since mid-March. It’s by far the longest stretch he’s been away from the job since spending four years in the U.S. Air Force in the early 1950s.

That was also the only time he ever considered leaving his job at URI, he says.

In 1952, Sciola signed up looking to serve in the Korean War. His older brother, Clemente, known as Clinton, was in the Air Force, serving on Okinawa as a radar technician and servicing aircraft headed to Korea. Stationed at various bases in the U.S., Jay, a crew chief, never got that close. “Even though I put in for every transfer that was going in any direction,” he says.

He was discharged in Laredo, Texas, in 1956 and latched on with a crop-dusting crew as part of the ground crew. Making good money for the mid-1950s, he says, he thought about staying on as the crew moved north to the upper Midwest.

“But then my dad contracted cancer and my brother was going to URI and working as a butcher in the First National store at night,” says Jay. “And they needed my help here, physical and financial. I don’t know even if those events hadn’t occurred if I would have stayed in Texas.”

About four years after returning to URI, he and Barbara were married. They settled in a house they built in Wakefield, with a view of Billington Cove, and had three children, Becky, Raphe, and Jodi. Over the years, the family traveled a lot, trips all around New England, annual drives down to Florida to visit his mother, sister and her husband, and to Montreal to visit family “too many times” because Jay loved the city.

Living in South County, he’s spent his free time golfing, helping his cousin work his lobster boat, and working his own skiff catching blue shell crab, dredging for scallops, and quahogging. “It’s really a beautiful place to live,” he says. “It really has become the hotspot.”

Over the years, he’s worked side jobs doing plumbing and heating, partly to put away money for retirement. When he first went to work at URI, state employees weren’t in Social Security, he says. When he got a chance to sign up, he passed. He was a young man with plans of building a house, and the 7 percent from his paycheck seemed a lot and the future a long way off, he explains.

Numerous efforts to get into the system failed, so retirement got pushed off. And he’s not ready to say when that day will come.

Asked what it takes to work the same job for 70 years, he answers, in the same no-nonsense way.

“I enjoyed the work I was doing. I became a licensed plumber, and I liked the people I worked with. I liked the direction that the University was going in. I knew someday it would be a highly accredited university. And it is.”