KINGSTON, R.I. – January 4, 2022 – There has been increased emphasis on the resilience of drinking water in recent years due to concerns over extreme events affecting water quality.

Joseph Goodwill, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Rhode Island, has been conducting research on water treatment methods that move beyond resilience and actually improve the quality of water during difficult times.

“I thought of an antifragile approach to water treatment in which our water systems could include technology that will improve performance under volatility,” said Goodwill. “It’s different than resilience. Resilience is when you experience volatility or stress and you either bend, but don’t break, or you break, but then recover quickly. Something that is antifragile gets better under that same volatility or stress.”

Goodwill’s research earned him a Royal Society of Chemistry Emerging Investigator Award, which highlights up-and-coming researchers who have been identified as having the potential to influence future directions in water research and technology. As a nominee, Goodwill was invited to submit a manuscript for peer review. His paper, “Moving Beyond Resilience by Considering Antifragility in Potable Water Systems,” was accepted and published in the Royal Society of Chemistry’s journal Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology.

According to Goodwill, antifragility is a versatile approach that could apply to many different systems.

“It’s a paradigm that could apply to all sorts of water treatment technologies or water system designs,” said Goodwill. “We are exploring one or two specific aspects of it at URI, but the hope is professors and researchers at institutions anywhere in the world might grab hold of this idea and find ways to apply it to their local systems.”

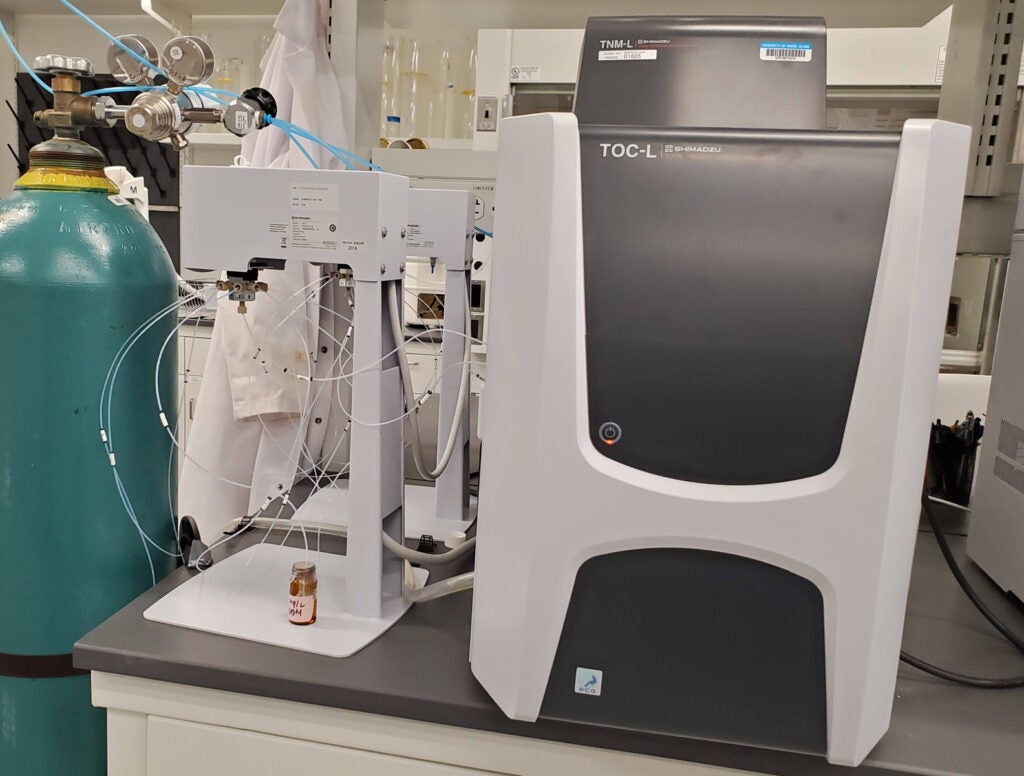

Two examples of emerging antifragile treatment processes Goodwill and the students in his lab are researching are the use of ferrate preoxidation and manganese oxides.

“I’m excited about the preliminary data we are generating on manganese oxides as a possible way to incorporate antifragility into a water system,” said Goodwill. “Manganese, which accounts for a significant portion of the Earth’s crust, is generally tolerated really well by humans. It’s not something typically used in water treatment, but I’m hopeful that by combining manganese oxide with oxidants it might be a unique way to do advanced oxidation.”

An unexpected real-world experiment

Goodwill’s ideas of using antifragility to improve water conditions were affirmed by research his group conducted with the Providence Water Supply Board.

“My students and I were tracking disinfection byproducts at one of the water storage tanks in Providence,” said Goodwill. “We were measuring trihalomethane, which is a compound present in all water that is chlorinated. When the city shut down due to the shelter-in-place order that was declared near the start of the pandemic, the water age went up temporarily. The formation of trihalomethane is a function of time, among other factors, so as time goes on, these chemicals become more abundant. We were doing this real-world experiment where we were seeing the impact a global pandemic had on this very specific component of our water system.”

Fortunately, Providence Water was equipped to handle this unexpected occurrence.

“Providence had the tools in place to deal with this, so we tracked the utilization of these tools,” said Goodwill. “They installed a trihalomethane-stripping aeration system in the tank just prior to the black swan event of the COVID-19 pandemic. We generated data in real-time on how a novel virus affected the levels of trihalomethane in a water storage tank. It was an interesting example of how a water system performs under stress.”

Aeration within the storage tank decreased the level of trihalomethane to well below the maximum contaminant limit. The use of aeration represented a form of resilience for Providence Water.

If a community isn’t aware of excessive levels of harmful chemicals in its drinking water or prepared to treat those chemicals as Providence was, it could present an opportunity to take one of Goodwill’s antifragility approaches. Goodwill’s research strikes the balance between addressing current real-world problems and anticipating future challenges.

“I try to keep one eye on what practitioners are doing right now,” said Goodwill. “As the land grant university in Rhode Island, I think one of our charges is to support our neighbors and help them with their problems. But I also like to keep one eye on the long-term future of water problems, which is one of my jobs as a professor.”