KINGSTON, R.I. – April 3, 2023 – A recent, widely reported study by researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center is the largest study to date to describe, in detail, whether the retina, a part of the eye, and the brain have related protein changes in Alzheimer’s disease.

The study, reported on CNN last week, looked at donated tissue from the retina and brains of 86 older adults, some with Alzheimer’s disease and some who were healthy controls. It’s the largest group of retinal samples ever studied, according to the researchers.

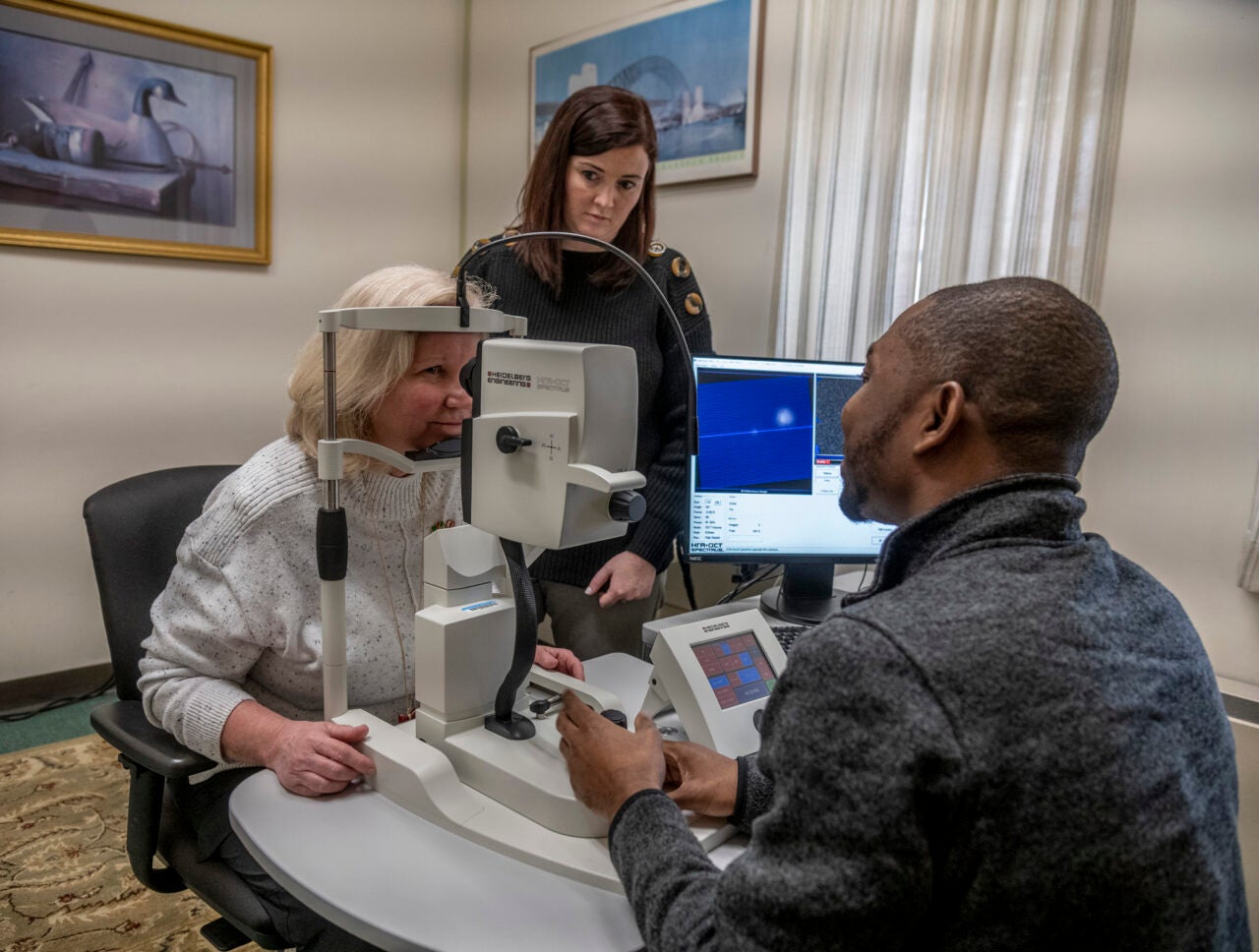

University of Rhode Island researcher Jessica Alber is the principal investigator of a new study that investigates whether a routine eye exam could be used as an early screening tool for Alzheimer’s. The study, Atlas of Retinal Imaging in Alzheimer’s Study (ARIAS 2), is funded through a five-year, $10.3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health.

We spoke with Alber, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy and George & Anne Ryan Institute for Neuroscience, about the new Cedars-Sinai study and how it complements her own exciting work.

A new study published by researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center found that the same changes in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease also can be seen in the eyes. Why is this important news?

This study looked at the brain tissue and retinal tissue from deceased patients who had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The researchers found that changes in certain proteins in the retina correlated with changes in the brain — namely amyloid-beta and tau proteins, which are the two key proteins associated with AD. This is important because they were able to see a detailed pathology of what is happening in the retina in this disease.

How does this relate to your own work?

This research is consistent with our own findings in a different population. We study people who are high-risk but haven’t been diagnosed with MCI or AD and don’t have cognitive symptoms. We are imaging their retinas and brains to understand if these techniques could be used as a screening tool during an eye exam or blood draw, or both, to potentially detect the types of changes in the brain that these researchers found. The study [at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center] took the important step of working directly on tissue in symptomatic patients in order to study the pathology. So, our work complements each other.

Why is it so critical to detect Alzheimer’s disease earlier?

Early detection of any disease leads to therapies. Over the last 10 years in AD research, there has been a shift to preventive medicine, to screening and catching it early. Two therapies approved in the past two years treat the earliest stages of AD and MCI, so this shift toward preventive medicine is directly responsible for driving innovation. These are the first in a line of new therapeutics that are coming along, and the eventual goal is to administer them before people experience symptoms.

Similar to cancer, being able to detect early and see what’s happening in the brain is really important. We can’t put everyone through a position emission tomography (PET) scan or lumbar puncture, but if we can do something that is administered in point-of-care settings, like an eye exam, then that is really going to help.

What are the next steps for your study, ARIAS 2?

We are working on startup activities right now — approvals, protocols, manuals, training — and hope to begin recruiting this summer. We’ll be recruiting around 180 participants, mainly adults between the ages of 65 and 80 who do not have any form of cognitive impairment. Once they are enrolled, we will follow them for three years.

It is encouraging to see this latest research on retinal tissue, which is an important piece of the puzzle to developing something clinically useful. I feel hopeful that we are advancing toward eventually being able to detect and treat Alzheimer’s disease before people begin experiencing devastating cognitive decline.