Why? Because hip-hop is art. And poetry. And music. And rhetoric. Because hip-hop is political science. And cultural anthropology. And linguistic anthropology. And philosophy. Because hip-hop is business. Big business. Because hip-hop is oral tradition. And zeitgeist. Because hip-hop is life. And death. And, for some, even salvation.

By Marybeth Reilly-McGreen

Derek Lacy ’19 raps about DEATH

“I lost my mom, Lori, to cancer when I was 15. One day my mom complained her back hurt. Next thing, she had a tumor. And then she was dead at 50,” he says. “At 18, I was just beginning to understand it. At 19, I started to make music.”

For Lacy, now 21, his mother’s unintentional legacy is a keen awareness of his mortality and a mad need to succeed as a rapper. “It’s made me go all-in. I got a lot of plays on this one song I recorded, so I reached out to [rap star] Mick Jenkins, and he tweeted about it, and it got 10,000 hits. I’m confident. I mean, back pain and life is over?! As bad as it is, death is also a motivating thing.”

In his childhood years, the music and lyrics of rappers like Eminem and Mac Miller spoke to Lacy. “I was most interested in the words. Rap validated me. Validated my emotions.”

Lacy says Mac Miller’s mixtape, Faces, kept him going when things went dark. “I can’t even explain how important it was to me. He helped me stay alive.”

Lacy’s desire to make a career of rap and hip-hop led him to study psychology and creative writing; poetry, in particular. “My lane is the prettiest words I can find and the grittiest emotion I can bring,” says Lacy.

News of Mac Miller’s death in September of an apparent drug overdose at the age of 26 left Lacy shocked, but determined as ever to pursue his dream of becoming a rap artist. Miller will be remembered as an artist who had the respect of everyone in the business, Lacy says. “He contributed to the hip-hop culture without stealing from it. I still listen to him every day and what I’ve learned from him is that you’ve got to start early and you don’t need all these connects [sic] to get started,” he says. “He taught me I can do this myself.”

The hip-hop industry generates $10 billion a year, and its reach extends far beyond music. Hip-hop is a culture with a language and symbols (think graffiti art) and an aesthetic. There are norms and values. There is a mythology and a reality—with the requisite heroes and villains. And increasingly there is recognition of its contributions by the cultural elite. This year, the Smithsonian will release the Smithsonian Anthology of Hip-Hop and Rap, comprising nine CDs with 120 tracks and a 300-page book of essays and photographs. In July, the Kennedy Center announced that it would award a special prize to the Tony, Pulitzer, and Grammy award-winning hip-hop musical, Hamilton. Last April, hip-hop artist Kendrick Lamar won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for music, the first nonclassical or jazz musician to receive the award. Also in 2017, a single painting by graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for $110.5 million at auction.

Need more convincing?

The PBS series Poetry inAmerica dubbed rap the most popular form of contemporary poetry in the world today. Scholars such as Adam Bradley, author of Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop, take it further, asserting that rap is the “most widely disseminated poetry in the history of the world.”

In the history of the world.

At URI, faculty are introducing critical study of hip-hop to their students through the lenses of philosophy and art. Alumni are making careers in the field, and students like Lacy are finding ways to integrate their love of hip-hop culture into their educations.

Because hip-hop matters, says MC and entrepreneur Theo Martins Jr. ’09. “It’s the driving force of innovation and ideas in popular culture. Hip-hop is solely based on being the first and the freshest, the ‘here’s what’s hot,’ and when you have that as the driving force for your ideology, you are in a constant state of discovery, looking and looking.

“It’s like poetic space exploration,”

Martins says.

Hip-hop is getting to the TRUTH

James Haile III, assistant professor of philosophy, has a lot of research interests: continental philosophy (especially aesthetics), philosophy of literature, philosophy of place, Africana philosophy and philosophy of race, the intersection of 20th century American and African-American literature and existentialism, writers Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, and Jean-Paul Sartre, black aesthetics, and especially the contemporary genre aesthetics of hip-hop. Oh, and Kendrick Lamar.

Haile recently wrote an article on Lamar’s album, good kid, m.A.A.d city, for the Journal of Speculative Philosophy titled, “good kid, m.A.A.d city: Kendrick Lamar’s Auto-ethnographic Method,” in which he argues that the artist “offers a new way of thinking about hip-hop as a whole, not simply as a capitalistic enterprise or as a ‘black news’ channel, but as a distinct method for collecting data and understanding the experiences and existence of black people.”

What artists like Lamar and graffiti artist Basquiat are doing, Haile says, is blowing up an idea and creating from the fragments. Kendrick Lamar takes the West Coast narrative and gives you those elements in different pieces. It sounds chaotic,” Haile says, likening Lamar to Miles Davis.

“The more you listen, the more you understand that Lamar plays around with voice as a way of shifting perspectives. He plays around with cadence like Wright’s Black Boy,” Haile says. “Richard Wright’s Black Boy is a collection of ideas. Lamar is a collection of ideas.”

In the shattering of ideas, Wright and Lamar are doing the work of philosophers. It is work Haile knows intimately. He is writing a book on Black art to be published by Northwestern University Press. “The history of philosophy is one of blowing stuff up,” Haile says. “But we don’t do that anymore. We don’t say, ‘Let’s blow up the conceptual framework, the idea.’ We fear being out on the ledge alone.” Haile’s book is about the destruction of thought. “It’s a book about Black art, which is, in itself, Black art. It doesn’t read like a straightforward narrative. It’s constantly moving—a moving target.”

So, how does a philosophy professor use popular music to convey such weighty ideas as the destruction of thought or the nature of being to 18-year-olds? He meets them where they live. He talks about the title track of good kid, m.A.A.d city: “Sing about me.” He notes that Lamar alters his voice to tell others’ stories in their voices, creating a conversation in which he channels all parts.

“Kendrick Lamar is switching pronouns in a single sentence! Shifting perspective,” Haile says. “Rather than speaking for those who do not have a voice, Lamar blends their voices as his own without subsuming their voice,” Haile writes in “good kid, m.A.A.d city: Kendrick Lamar’s Auto-ethnographic Method.” “When one is listening and hears Lamar, one is also hearing all the other voices that are not his.”

So to study Lamar is to contemplate the very nature of identity?

Haile grins. “Lamar gets us out of the politics of our identities and more to something significantly true.”

Hip-Hop is finding a VOICE

Hip-hop artists so revere words that they profane them. They add and subtract letters from them at will. They stretch and pull them like gum wound round the finger. They take two words and mash them together. They take one word and split it like an atom. And the fallout is music—and more: insight into the human condition, the outpouring of a soul expressing love, lust, anger, frustration, hatred, unity, pride, virtue, and vice: it’s all there. Hip-hop has been criticized for its misogyny, homophobia, racist language, and glorification of violence. But is it so different from any other art form? Hasn’t the artist always sought to mirror back to society its triumphs and its failures? Hasn’t art always been about giving voice to thought?

Africa Costarica Smith ’18 loves words. She writes a haiku a day as a kind of personal check-in. “I’ll write in my journal, just write out what I see, and then condense it. My parents are house-hunting right now. I wrote a whole thing about a house being condemned. I ended it with “empty of everything being full,” Smith says. “So I’ll start a poem from that line.”

Smith, a spoken-word artist and former member of URI’s Slam Poetry Club, intends to make a career in university administration. Art is her outlet. “My parents grew up in New York City and Brooklyn,” Smith says. “Music, hip-hop, has always been a part of my family’s life. My dad had a boom box and an Afro and was into freestyling. My parents used music as a connector. There wasn’t a day music wasn’t played in my house.” Smith’s dad has a beat machine. “He’d be riding the rhythm. It got him out of bed in the morning,” Smith says.

Smith, who competed in slam poetry contests at URI, says the allure of rap and hip-hop is its accessibility. Still true to its urban roots, hip-hop is narrative in the tradition of the epic poem, speaking to universal truths, meant for mass consumption. This is the language of youth speaking their truth.

“Hip-hop and rap give people a chance to tell their story,” Smith says. “And the more woke you are, the harder it is to sleep. The more woke you become, the more aware you are of injustice in the world.”

As an undergraduate, Smith sometimes found herself the only nonwhite person in a classroom. Writing and performing proved a release from the unease she sometimes felt. “Poetry helps me put it all into perspective. Then I can reflect and feel better about things. In the black community, we don’t talk about mental health. Rap and poetry address personal and societal issues,” she says.

“People can find themselves in someone else’s story and not feel so alone in this world.”

Hip-hop is taking a STAND

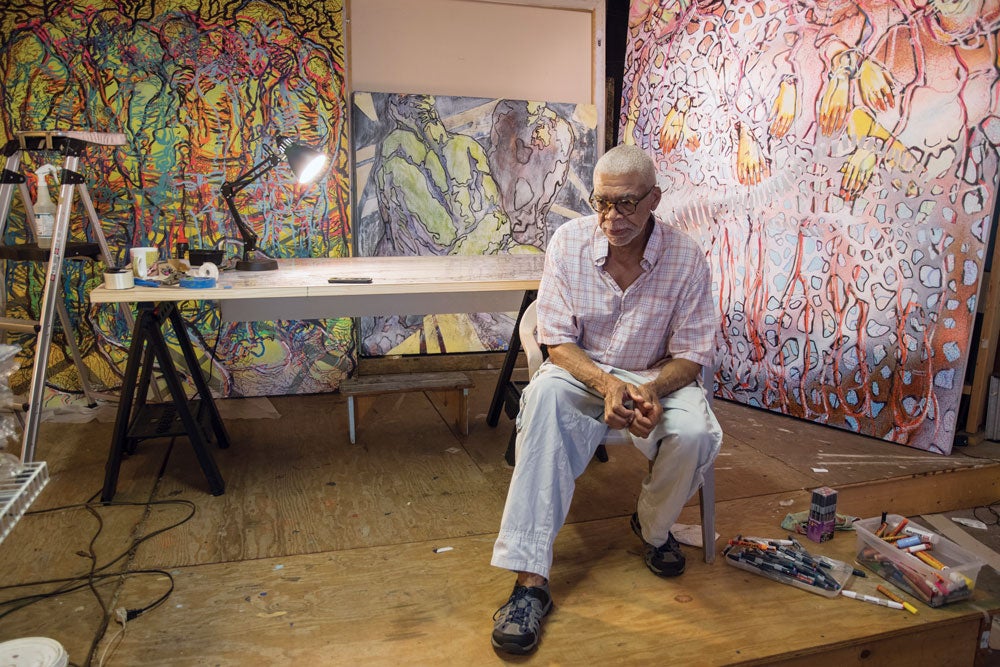

Bob Dilworth, professor of art, teaches painting, drawing, design,

and African-American art history in the Department of Art and Art History, in addition to chairing Africana Studies. Standing amid his larger-than-life paintings in his Providence studio, he says that he considered naming his next show “Black Lives Matter.”

“The idea for this series of paintings, for the new work I’m doing, is to focus on lives affected by shootings and killings of young kids in the streets,” Dilworth says. “There are families affected. We never hear from the moms, the dads, the aunts and uncles. We never hear how they feel.”

Then Dilworth watched a get-out-the-vote ad featuring former first lady Michelle Obama. In it, she exhorted everyone to vote. Not just Democrats, but all people. It moved him. “I thought, how wonderful! Her concern isn’t about black or white or yellow or green. It’s about everyone voting. She saw it on a higher level, and everyone’s getting the call,” Dilworth says. “It’s a call that we need to stop, take pause.”

“The way the world has to change is through acceptance and through love,” Dilworth says. So now the show’s working title is “Black Love Matters: The Aesthetics of Repair.” “The suggestion is that something needs addressing,” Dilworth says. “We need to create a new space for repairing what’s wrong.”

Art as activism plays well on the grand canvases Dilworth creates using acrylics and spray paint, Sharpie markers and fabric. It’s an involved process. Dilworth photographs and interviews the subjects of his paintings. Then he makes stencils on grids that are reproduced on the canvases. Square by square, his drawing grows until figures tower and a stepladder is needed.

While his is not graffiti art, per se, Dilworth’s paintings echo the energy, movement, and emotion of graffiti art. Standing in front of a painting in its infancy—several life-sized female figures in black outline rendered over Montana Gold acrylic paint—Dilworth ruminates on art’s provocative nature.

“Part of what’s happening is artists of color have had to create a visual expression of what’s happening in the country today, and how to counteract or address the issue is through art,” he says. “Art has always been a way to comment, to give some expression to what’s going on. Art reflects life, reflects people who are trying to understand a rapidly changing society, a rapidly changing world. And they’re expressing it in novels and poetry and painting and song,” Dilworth says. “Art helps other people to understand what’s going on in their world. Artists can create, through metaphor, a window into what’s going on in the world.”

Teaching students about hip-hop artists like Basquiat, Banksy, and Keith Haring exposes them to the idea that they, too, can contribute a verse. “Basquiat had a unique perspective on life. Basquiat, Romare Bearden—these are the people you study. The ones that have that unique vision,” Dilworth says. “Sometimes it takes someone who’s way out in left field to help us so that we can see the world in the unique way they’re looking at it.”

Hip-hop is taking your SHOT

URI alums and rappers Duval “Masta Ace” Clear ’88 and Sage Francis ’99 stepped into the world of hip-hop after graduation. Both recommend that path, in that order.

“The main reason I went to URI was to get on the radio,” Francis says. “I grew up listening to WRIU’s hip-hop shows, back when DJ Curty Cut had a show. I ended up visiting the station and rapping on it whenever the DJs would allow me to. I became a fixture to the point where I was actually given a show before I was even a student at URI. It was fun as hell and it helped us whip up a legitimate hip-hop scene in Rhode Island.”

Francis is the founder of Strange Famous Records, an independent label he established in 1996 because, according to his website, he decided to stop waiting around for a label to discover him. His advice to up-and-coming college rappers comes in the form of a question: “Why are you on a campus if you’re an up-and-coming rapper?” His answer and his advice: “You’re not. So have a fallback plan. Get that degree.”

Thirty-year hip-hop veteran Masta Ace offers similar advice. He counsels those who would follow his path to be equal parts artist and pragmatist. “I tell young people that all things are possible. Look within and find that strength, that drive, that desire—and go for it. But make sure music is not your plan A,” he says. “When I was starting out, one in 1,000 made it, got a deal, put a record out. Now, these kids are up against the world. The odds are much worse now. My marketing degree from URI was my plan A.

“You don’t want to wake up at 35, sleeping on your mom’s couch, eating your mom’s food, with a baby here and one on the way.” Ace says. “It’s almost cliché. You don’t want that. Make music your plan B.”

Hip-Hop is keeping it REAL

Poet, essayist, and master’s degree candidate Reza Clifton ’03 is a

former WRIU DJ who introduced the campus to female rappers and musicians through the radio show Voices of Women. “The reason hip-hop will continue is because it still represents the voice and mood of the culture of the oppressed,” Clifton says. Hip-hop is a genre where you don’t need to have formal music training; you don’t have to be able to play the violin or the piano.

“Hip-hop was conceived of and grew in an underfunded city at a time when cuts to music programs were happening in schools,” Clifton continues. “Hip-hop was like The Little Engine That Could— pressing on whether there was funding or not. It is a message of self-determination that underlies the founding of hip-hop.”

Derek Lacy ’19 also raps about life. He is fully funding his education with an inheritance he got from his grandfather. He’ll be the first of his family to graduate from college. If he could, he’d have his future as a rapper start today. “It’s the streaming age, and rap is a young man’s game,” Lacy says. “I gotta really get myself together here. I just want to make people feel something.” To hear him is to believe he just might. •

Interesting feature article! Coincidentally, URI ‘14 Engineering Grad and Hockey Captain, Sean O’Neil just contributed to a hip hop album that just debuted #1 on Billboard. Sean’s guitar is featured in Metro Boomin’s, “No More” on the just released, All Heroes Don’t Wear Capes Album. Sean’s experiences and collaboration with Metro Boomin are a tremendous example of how people from very diverse backgrounds can come together and unify through Music. Sean’s younger brother Ryan, URI ‘21 is currently enrolled in the School of Engineering as well. Go Rams!