“I’m a proponent of getting your hands wet.”

Studying marine invasive species is complicated. To begin with, not all invasive species are bad for the areas they invade. Others damage or destroy the habitats they migrate to. These URI scientists are working to monitor, understand, and manage these species.

By Marybeth Reilly-McGreen

Millions have come by boat, tucked away in holds, shedding babies through ballast water. Swimming, scuttling, drifting, they deploy under cover of night or in broad daylight. It makes no difference. Covert operations aren’t necessary. And while there will be combat and casualties, maybe even annihilation, the campaign is waged quietly, often underfoot and, while not necessarily out of sight, nonetheless undetected by most.

Save for scientists such as Carol Thornber, Niels-Viggo Hobbs, Ph.D ’16, and Lindsay Green-Gavrielidis, who’ve made it their work to research invasive species and to train new generations of scientists in monitoring and mitigating them. Because the effects of invasive species can range from nuisance to deadly.

Invasive species are nonindigenous plants or animals whose arrival often adversely affects habitats–economically or ecologically. Management of invasive species varies. In some cases, physical or mechanical control, i.e., removing the invasive species from the habitat through traps or barriers or, in the case of plants, mowing, is possible. In some instances, chemical (pesticides) and biological controls (introducing predators, parasites, or pathogens) have been employed. Still another option is cultural management: manipulation of the habitat that makes it less hospitable to the invader.

Asian Shore Crab

Sound troubling? It can be. Books on the subject bear ominous titles reminiscent of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds or virtually anything written by homegrown horror author H.P. Lovecraft. Examples: Killer Algae: The True Tale of a Biological Invasion; The Aliens Among Us: How Invasive Species are Transforming the Planet – And Ourselves; Inheritors of the Earth: How Nature is Thriving in an Age of Extinction; and A Plague of Rats and Rubber Vines: The Growing Threat of Species Invasions.

Once they arrive, the invaders’ strategy follows a predictable, four-pronged plan: eat, reproduce, fight, endure. Trouble is, things are often out of hand by the time human beings catch on. Case in point: the red Asian seaweed Grateloupia turuturu that was first discovered in Narragansett Bay in 1996. Twelve years after this species was introduced through ballast water from trans-Atlantic ships, it had spread across more than 400 miles of New England coastline from Maine south. It is a nuisance for fishers, gumming up lobster traps and pots, and it blankets beaches. It also smells when dried. Not great for a state whose primary industry is tourism.

And that’s just one invasive species. Scientists estimate at least 25 new fish and invertebrate species have arrived in New England over the past couple of decades. Some have substantial ecological impact, says Hobbs. Scientists like Hobbs are quick to note, though, that invasive species aren’t all bad. They’ll tell you the term “invasive” is generally pejorative and, so, a seriously problematic word to use when classifying a species new to town. “Invasive” is likely both incorrect and very troublesome, Hobbs says.

It’s a sunny day in June. Hobbs and a group of students are in Newport, drawing up submerged slate plates tethered to docks and weighted with bricks to see what’s growing underneath, on, and around them. Docks are considered disturbed habitats, and boats are vectors for invasive species. A marina, then, is the first line for the introduction and propagation of an invasion.

A side conversation about an invasive jellyfish has Hobbs excited. There have been reports of a new-to-the-area type of jellyfish that has been attaching itself to eelgrass. Hobbs warns those present not to touch the jellyfish should they see them, as the jellyfish produce hallucinogenic effects–and “not in a pleasant way,” Hobbs quips.

“An invasive species of crab may push out native species, but also be a huge food source for commercially important fish.”

Back to the invasive species at hand. Hobbs is looking at a dark, bushy growth. It’s actually a group of organisms, colonial creatures, with the scientific name bryozoa. Hobbs notes that three years ago, they wouldn’t have encountered this, but it’s proved a hardy creature (remember that four-pronged plan: reproduces faster, better able to adapt, fast grower, not a picky eater). “Pretty much everything on this plate is invasive,” Hobbs says, looking at its occupants. “Ninety-nine percent of what we’re seeing is invasive species.”

In 2018, Hobbs became the first winner of the part-time faculty excellence award given by URI’s Office of the Provost. Hobbs, an adjunct instructor in the College of the Environment and Life Sciences, began teaching in 2003. He is an expert on invertebrates and marine communities in New England and is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Environmental Protection Agency. He studies crustaceans and has “heavily dabbled” in other species.

Asian Shore Crab

Hobbs notes the various creatures present on the slate to his students, who fill out pre-printed data sheets. “They’re a crash course on how to ID this stuff,” says Megan Major ’20, an undergraduate studying animal and veterinary sciences and wildlife conservation. Hobbs and his students check the plates every month. Some plates are left in the water for the whole season.

Up close, the plate’s residents collectively resemble a forgotten sandwich in a bagged lunch that has been sitting in a backpack all summer. Think slime in varying shades of rust, upon which sit squishy colonies of beetle-sized tunicates, or sea squirts, aptly named as they squirt seawater when pressed. “They’re actually closely related to us,” Hobbs says.

Hobbs picks up a bug-ish looking invertebrate from the slate and holds it in his hand–a tiny, many-legged crustacean you’d freak out to find in your bathing suit. “Isopods are adorable,” one student enthuses. “They’re so cute.”

“You have to admire what a species is capable of,” Hobbs says.

The conversation turns to how invasive species can be a boon for the environment. That’s why some would prefer the term “introduced,” saving “invasive” for those species causing ecological or economic damage. An invasive species of crab, for instance, may push out native species, but also be a huge food source for commercially important fish.

“Some species have so much value that people look past it,” Hobbs says. “Once an invasive species is introduced, though, it’s hard to eradicate it.”

One way to mitigate an invasive species’ impact: Eat it.

To say Lindsay Green-Gavrielidis studies seaweed is certainly true, but that just doesn’t begin to cover it. A seaweed enthusiast, she’ll tell you it’s a foundation species, providing habitat and structure for innumerable organisms. It is the base of many food webs. It serves its ecosystem through the extraction of excess nutrients from coastal waters.

And it’s great in lemon cake.

Green-Gavrielidis has her Ph.D. in plant biology and is at URI as a postdoctoral researcher. She studies sustainable aquaculture, the ecology of seaweed blooms, and the impact of introduced non-native species on native faunas and floras, among other things. She and Hobbs regularly dive 24 sites around the state, monitoring seaweed activity.

“I always wanted to be a marine biologist,” Green-Gavrielidis says. “I wanted to study dolphins and whales.”

“Seaweed blooms can smother other things living in an area and are encouraged by excess nutrients in the coastal environment.”

Green-Gavrielidis grew up in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, nowhere near the ocean. “My mother said my first word was ‘whale,’” she recalls. As a girl, she sat and read encyclopedias and typed up little profiles of whales. College introduced Green-Gavrielidis to other compelling things that lived in the ocean, such as seaweed blooms and excess nitrogen.

Seaweed blooms can smother other things living in an area. Microbial decay reduces available oxygen. Seaweed blooms are encouraged by excess nutrients in the coastal environment, Green-Gavrielidis says.

Asian red seaweed

“We’re putting too much nitrogen into the water,” she says. Like Hobbs, Green-Gavrielidis is hesitant to categorize a species as good or bad for the environment. “We don’t know enough to determine whether something is of benefit or not. That takes time and research,” she says.

Green-Gavrielidis is working with local oyster fishers on kelp farming. She’s studying whether this type of brown seaweed might be a food source as well as examining quantitative data on changes in the local habitat over the past 30 years. It is a great field for students to get into, she says. And URI’s proximity to the ocean makes for unparalleled learning opportunities.

“I’m a proponent of getting your hands wet and observing the things that you study in their natural environment,” Green-Gavrielidis says. “It gives us a good sense of what’s happening in essential habitats.

“Narragansett Bay is one of the best-studied estuaries in the country. It’s easily accessible, well-populated, and has a good collection of vigorous research universities in the area, as well.”

Green-Gavrielidis is also interested in seaweed as a food source. The invasive species Grateloupia turuturu, for instance, is a commercially important food source in East Asia, its native habitat. “Marine life factors into toothpaste, ice cream, and powdery non-dairy creamer. It’s a clarifier in beer brewing,” she says. “The vast majority of seaweeds are edible.”

Ready to Try Cooking with Seaweed?

Lindsay Green-Gavrielidis recommends these websites for ordering seaweed. They are, she says, “mostly Maine-based, because their industry is bigger.” Order sea lettuce, then try her favorite recipe for lemon cake with sea lettuce.

Lemon Cake with Sea Lettuce

from Seaweeds: Edible, Available, and Sustainable, by Ole Mouritsen.

Serves 4

Milder varieties of seaweeds, such as dulse and sea lettuce, can be used for baking, both in breads and in cakes. The seaweeds impart a fine-tuned salty taste and at the same time add a colorful touch—red from dulse and green from sea lettuce.

Lindsay’s conversions from grams to cups/tablespoons and from Celcius to Fahrenheit are noted below in parentheses.

2 tbsp flakes of dried sea lettuce or dulse

120 g white flour (1 cup)

120 g butter (8 tpsp/1 stick)

2 eggs

120 g icing (or confectioner’s) sugar (1 cup)

2 organic lemons

2 tsp baking powder

Sugar

Grate the zest from one of the lemons and mix it with the butter which has been melted with the icing sugar. Add the seaweed flakes, flour, egg yolks, and baking powder and mix everything together. Beat the egg whites and fold them into the mixture. Pour into a greased ring pan and bake for 20–25 minutes at 200°C (400°F). Squeeze the juice from the lemons and bring to a boil with sugar to taste. When the cake is baked, turn it out of the pan and drizzle the sweetened lemon juice over it.

When Carol Thornber was six years old and vacationing in Oregon, she picked up a book about whales and dolphins at the public library. The New Jersey native, now a professor of natural resources science and associate dean of research in the College of the Environment and Life Sciences, fell in love with the ocean and its creatures in that moment.

As an undergraduate studying biology at Stanford University, she learned how to scuba dive in Monterey Bay. “And I saw all this life there: fish, seaweeds, crabs scuttling around–the whole bit.”

She gravitated to marine biology and ecology as she studied the rocky shores and tide pools of California. “There were lots of scientific studies done on crabs but little was known on the basic biology of some species of seaweed.”

Further investigation raised questions. “Seaweeds don’t live in isolation,” Thornber says. “As I’ve gone along in my career, I’ve seen things start to change and wondered why. Species disappear or new species come into the mix.”

In graduate school, Thornber studied invasive seaweeds that had become established in Southern California. “If you lie down on a floating dock, there’s all sorts of stuff there, primarily because of boat traffic.”

“As I’ve gone along in my career, I’ve seen things start to change and wondered why. Species disappear or new species come into the mix.”

Invasive seaweeds are a tricky thing to manage. Harvesting some types actually triggers reproduction. Eradicating other types is an expensive and disruptive process. Thornber maintains a lab and has an active research program. She is particularly interested in another species of red seaweed, Dasysiphonia japonica, which reproduces with disruption.

“It’s a good invader because it can fragment easily. A piece breaks off and starts to grow,” Thornber says. “This species is appearing on both sides of Cape Cod. South of the Cape the water is warmer than the north because of currents. This one quickly spread around.

“We see huge piles of it washing up on beaches. It’s an eyesore for coastal communities: little red puffballs in the water,” she notes. It’s become a dominant seaweed on the Eastern Seaboard.

So what’s to be done? This is not a field of quick fixes or simple answers. In monitoring the spread of invasive species, scientists can make recommendations ranging from containment to eradication, as well as prevention of future invasions. What is certain is that international trade and travel are not going to cease–so these issues will amplify over time.

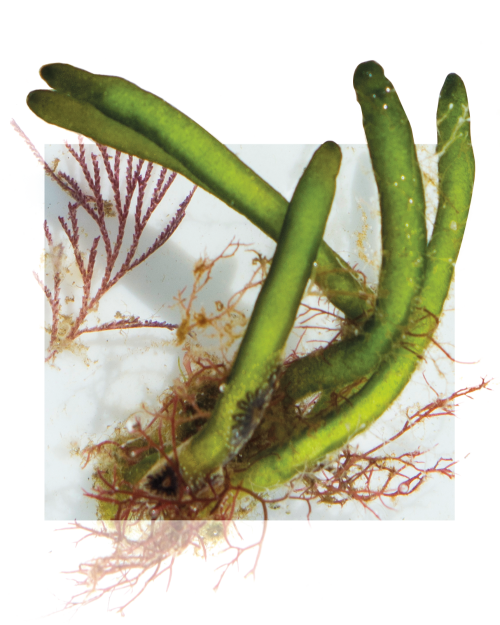

Green sea finger

And, not all introduced species survive in their new habitats. The Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis, for instance, which has done millions of dollars’ worth of damage on the West Coast, started showing up in New York. It didn’t fare well, though, and ended up failing to establish itself. And a species of European shrimp that showed up in Narragansett Bay appears to have recently disappeared in Salem Sound, where it was first introduced. Nature’s version of game over.

“It’s important for us to understand our natural environment because species are changing due to human action,” Thornber says. “We track these populations and see what happens to them.

“Sometimes species just disappear,” Thornber adds. “That kind of ebb and flow happens in nature.”

Homo sapiens: Take note. •

Is green sea finger (codium fragile) edible?

Dear Anna,

Lindsay Green-Gavrielidis shares the following response to your question:

I’ve never eaten Codium myself but it is edible. It’s listed in Irish Seaweed Kitchen by Prannie Rhatigan as a good source of iron and trace elements. I also found this recipe online: https://www.diannedelaveaux.com/codium-fragile-recipe.

Always good to get questions and comments from readers. Thank you!

Barbara Caron

Editor-in-Chief

University of Rhode Island Magazine