URI’s History of Student-Led Civil Rights Activism

The 2020 “moment” of racial reckoning is the latest iteration of what is, in truth, not a moment, but a longstanding struggle for racial justice in the United States. At URI, student-led protests have been some of the most powerful catalysts for change.

By Grace Kelly

“The appalling silence of the good people is as serious as the vitriolic words of the bad people,” said the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. from the podium.

Five-thousand students, professors, and staff sat in Keaney Gymnasium on a mild October afternoon in 1966, soaking up the words of the civil rights activist.

“It would be a great benefit to the students today to understand how we have arrived where we are—at what young people call ‘the moment.’”

—Frank Forleo ’74

King’s words—as well as the words and actions of others—inspired change. Over the years, URI students, staff, and faculty spoke out against injustice, protested inequality, and honored those who fought the true fight. Buildings were occupied, activists gathered, and organizations formed.

“All or most of the progress that has been made on campus has come, if not immediately, in the years subsequent to student protests,” says Abu Bakr ’73, M.S. ’84, M.B.A. ’88.

Frank Forleo ’74 was assistant director for Talent Development from 1975 until his retirement in 2016. His wife, Sharon Forleo ’72, M.A. ’94, also served Talent Development as associate director. The Forleos were the recipients of the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2019 URI Diversity and Inclusive Excellence Awards for their 40+ years of service. President David M. Dooley praised their dedication, saying, “The cumulative impact of your love for the students of the University of Rhode Island, particularly those students who, for very good reasons, felt marginalized, ignored underappreciated and disrespected, is extraordinary.”

Africana studies, the Multicultural Student Services Center, the Black Student Union, the creation of the chief diversity officer position, and resources to address racism and bring about equity on campus all have their roots in the student protests of 1971, 1992, and 1998.

“It’s such a pivotal part of our history, but not necessarily part of the narrative that we tell about URI,” says Mary Grace Almandrez, chief diversity officer and associate vice president. “We all know about Rhody Ram, we know the fight song—there are certain parts of our narrative that we continue to perpetuate, but not necessarily that activist history.”

“I always wish that there was a way for students to understand the long history of the struggle,” says Frank Forleo ’74.

“It would be a great benefit to the students today to understand how we have arrived where we are—at what young people call ‘the moment.’”

1971

In 1971, students took over the administration building, protesting the lack of diversity at URI and cuts to funding for the Talent Development program. The protest led to several important changes, including securing funding for Talent Development for subsequent years.

1971: The Push for Recognition and Respect

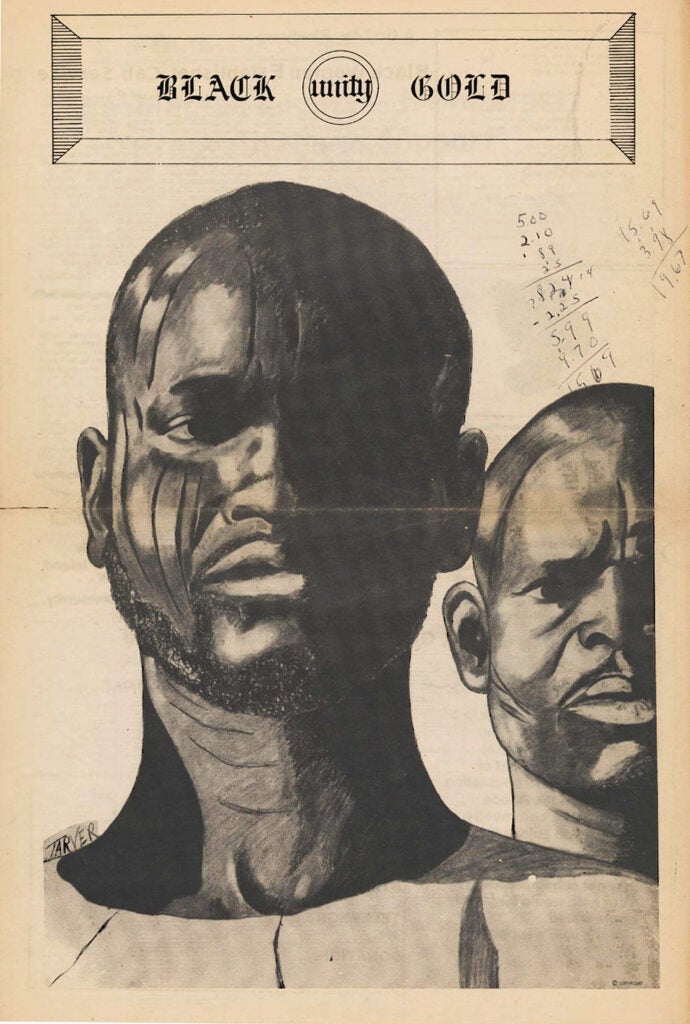

Valerie J. Southern ’75, M.C.P. ’80, is the president of VJS-TC, providing expert consultation in planning, management, engineering, and design of transportation systems. Before establishing her practice, she held various municipal, state, and federal transportation planning and policy positions, including serving as the deputy secretary for transportation planning and capital programming for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. While a student at URI, she started and served as editor-in-chief of the influential student newspaper, Black Gold.

When Valerie Southern ’75, M.C.P. ’80, first arrived at URI in 1970, she was stunned at her treatment.

“When I arrived and started participating in my classes, which I was used to doing, I realized that there was a difference,” she says, “not because they didn’t know who I was, but just because I was Black.”

Southern grew up in Jamestown, Rhode Island, the daughter of a Naval serviceman, attending St. Catherine Academy in Newport, where she was encouraged to participate in class.

But things were different for her at URI.

Classmate Forleo explains: “When I started at URI, it was lily-white. There were some student-athletes of color, and there were a smattering of African-American students, but the numbers were very small.”

After a hiatus when he fought in Vietnam, Forleo returned to URI to some small improvements. “By the time I came back in ’69, things had changed a little because the Talent Development (TD) program was created in ’68. But the group was still pretty small.”

“They weren’t used to Black students, and there were hardly any Black faculty, hardly any,” she says.

And in 1970, Southern was part of that small population, around .001 percent.

“I realized that professors were ignoring me. I would raise my hand, say, ‘I have an idea,’ and they’d be like, ‘Yeah right, hold on,’ and all the other students would get their say,” she says.

“It was just signs—some subtle, some very blatant—that we weren’t considered worthy of the experience that the state university was offering.”

So, in 1971, the Black students took matters into their own hands.

“We decided one evening to take steps to be seen and heard.”

—Valerie Southern ’75, M.C.P. ’80

“We got together and decided we needed to try to communicate to the University that we were feeling neglected, as though we weren’t respected—that the institutional racism was actually encouraged as opposed to examined,” says Southern. “So, we decided one evening to take steps to be seen and heard.”

They requested a meeting with then-President Werner Baum; when this request was ignored, they decided to take a more dramatic approach.

“We went into the [Carlotti] administration building and told everybody to leave, we’re going to lock the doors. They realized we were serious; they all left, and we chained the doors,” says Southern.

The 50-some Black students then hammered out a list of demands. “We, the black students at the University of Rhode Island, because of an increased lack of respect from the racist administration and the Student Senate (Tax Committee), plus a lack of Black representation, hereby declare a takeover,” they wrote.

“We demand that the freshman enrollment for fall ’71 contain 300 black students,” demand 4 read, while demand 13 required the University to “appoint a committee approved by the Afro-American Society to develop a Black studies Program.”

During the first week of May, 1971, they occupied Carlotti for days, giving speeches on the balcony, watching as a large crowd grew on the Quad in front of them, and gratefully accepting food from friends to keep their takeover energized.

Wednesday evenings at URI were normally quiet. “About the biggest thing on campus is an intramural softball game,” quipped a May 7, 1971, issue of The Good Five Cent Cigar.

Students occupying the administration building address a crowd on the Quadrangle. In addition to securing funding for the Talent Development program, the student protesters succeeded in establishing a Black studies program and a Black student organization at URI.

But the evening of Wednesday, May 5, was different. Southern remembers it vividly.

“Suddenly, the police showed up and they broke the glass and stormed in, grabbed us and threw us outside. I thought they were going to kill us, I mean I literally thought, ‘This is it, my life is over, but it’s for a good cause,’” Southern says. “I closed my eyes and just kind of hugged myself; I could feel rough hands picking me up, and I was like, ‘They’re probably going to beat me up or kill me,’ and the next thing I knew, I was lying on the grass outside.”

The occupation of Carlotti was over, and Southern was unharmed, but the experience has stayed with her to this day. “It was very, very traumatic,” she says. “For the rest of my life, I participated in marches and protests, but that was the one that took my mind away.”

The takeover was not in vain.

“The end result is, we got a Black studies program, we got an officially established Black student organization—and they gave us a van so we could do community work in the South Kingstown community,” Southern says. “It was a result of just speaking up.”

Southern also started a successful student paper called Black Gold.

“Black Gold was designed expressly to give students a voice,” says Bakr. “And to also express their literary and creative sides. It was an outlet for students to not only be able to read, but to contribute to.”

Bakr and Southern were also involved in planning the annual Black Cultural Weekend. “It was like a festival and the people that passed through—the Temptations, Alice Coltrane, various poets, intellectuals, it was just fantastic,” Southern says. “Through hard work, we were able to bring notables of American Black culture to URI and it was really just wonderful.”

1992

In 1992, President Robert L. Carothers (seated at center) and Vice President for Student Affairs John McCray (standing behind Carothers to his left) met with students who took over Taft Hall to protest a truncated Malcolm X quote carved into the library facade. Two Hundred students participated in the takeover, which was led by the newly formed Black Student Leadership Group (BSLG). The students successfully negotiated important advances, including reconstruction of the Multicultural Student Services Center, establishing a chief diversity officer position, creating the library’s Malcolm X Reading Room, and initiating an Africana studies major.

1992: Why Haven’t Things Changed More?

Karoline Oliveira ’94, M.S. ’03 , is the interim executive director in the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and special advisor to the president of Life University. Prior to that, she served URI as an academic advisor and transitions coordinator for Talent Development, part-time faculty member in human development and family studies, and assistant director and acting director of the Multicultural Student Services Center.

While the 1970s were a pivotal decade for race relations at URI, students some 20 years later found there was still much to be done.

Karoline Oliveira ’94, M.S. ’03, fondly remembers her first experience on the URI campus, the summer before her first year.

“I was a Talent Development student and, like the majority of the students on campus who were students of color, I came through the TD program,” she says.

The TD program started in 1968, bringing students from diverse backgrounds to the state university. The summer program was a way for TD students to prepare for the fall and get to know the campus.

“You have this amazing experience where you’re connected with students you can relate to. We came from similar backgrounds, many of us from the inner city of Providence. We felt like we belonged,” she says.

But then came the fall.

“And then you begin to experience isolation, microaggressions, and the world all of a sudden becomes real.”

— Karoline Oliveira ’94, M.S. ’03

“In the summer you had this time of friend-making and navigating the campus—an amazing experience, and then fall comes and you realize, ‘Wow, there aren’t that many of us here,’” Oliveira says. “And then you begin to experience isolation, microaggressions, and the world all of a sudden becomes real.”

A string of incidents compounded this sense of “otherness” and disrespect, including mistreatment by the URI police and the misquote of Malcolm X on the library.

“The [Black students] were being isolated and unfairly watched by the police,” says Forleo, who was the assistant director of Talent Development at the time.

The lid blew when a Malcolm X quote was chiseled onto the façade of the library, but was a truncated version of the original quote. The inscription on the library read, “My alma mater was books, a good library. I could spend my life reading, just satisfying my curiosity.”

But the original quote was much more damning.

“All or most of the progress that has been made on campus has come, if not immediately, in the years subsequent to student protests,”

—Abu Bakr ’73, M.S. ’84, M.B.A. ’88

“I told the Englishmen that my alma mater was books, a good library. Every time I catch a plane, I have with me a book that I want to read. And that’s a lot of books. If I weren’t out there every day battling the white man, I could spend the rest of my life reading, just satisfying my curiosity.”

“That was really an issue for the students,” says Forleo. “And the other thing besides misquoting Malcolm X was the quote from Thomas Jefferson on the other side if the library. It really angered the students that a slave owner was being quoted in stone and Malcolm X was being misquoted in stone.”

Abu Bakr ’73, M.S. ’84, M.B.A. ’88, transferred to URI from Duke in 1970 as a scholar-athlete. As an undergraduate, he served as a counselor for the Talent Development program and, upon graduation, as its summer director. He played on URI’s men’s basketball team, serving as captain for two years and earning distinction as one of URI’s top all-time career rebounders. After a successful basketball career in Europe, Bakr returned to URI to complete two master’s degrees. He served URI as an administrator for 35 years—in many capacities, including executive assistant to the president, and interim associate vice president for community, equity and diversity and chief diversity officer. Bakr retired from URI in 2013.

Coupled with the crumbling, condemned building where the Black student group Uhuru Sasa held its meetings, and other racist incidents, the students took action.

“We really had had enough,” says Oliveira, who was a member of the Black Student Leadership Group (BSLG).

“A group of around 30 students made a determination to take over Taft Hall, along with another 300 people who were involved when they finally took over the hall and renamed it Malcolm X Hall and issued the 14 demands,” says Forleo. “The demands were all about changing the numbers of students of color at the University, having more facilities and support structures for students of color, and curricular change, which was still a big issue, because African-American studies had not yet become a major in those years between 1971 and 1992. The students asked, ‘Why haven’t things changed more?’”

Two days after the takeover of Taft, then-President Robert Carothers met with the students to hear their grievances and listen to their demands, a far cry from the reception students had received in 1971.

“This was historic,” says Forleo. “I mean, it’s quite extraordinary. Carothers supported some of the demands. The TD program grew, African-American studies became a major, other curricular things were offered—there was change.”

A multicultural center was also built in the center of campus, creating a safe and accessible meeting space for students of color.

For Oliveira, this was a powerful moment that reminded her of what her father had always told her: “You stand for something or you fall for anything.”

“Being in that building, for me, I felt so empowered that no matter what happened, even if I was kicked out of school, I was standing up for what I believed in,” she says.

1998

In 1998, a cartoon published in The Good Five Cent Cigar set off protests led by Black student group Brothers United for Action. The controversy exposed ongoing racial tensions at URI.

1998: Still Fighting Racism with Growing Solidarity

In 1998, another protest against injustice was led by the Brothers United for Action (BUA) after the publication of a racist cartoon in The Good Five Cent Cigar.

“There were only six years between the Black Student Leadership Group [takeover of Taft Hall] and the BUA protests. That was not a very wide gap before another major movement occurred,” says Forleo. He still vividly remembers the BUA-organized march from Taft Hall to the Memorial Union, a massive show of solidarity.

“They had an enormous following of students of all races and ethnicities,” Forleo says. “When the BUA stepped off for their march … by the time the first members of BUA got to the newspaper office in the Memorial Union, there were still people in line coming from Taft. It was one of the biggest demonstrations I had ever seen at the University.”

2020: The Moment

Today, the fight to bring racial justice and equity to URI continues.

“I believe that URI has made some strides,” says Oliveira.

“Some students are just learning about racism and microaggression, some know a little, and some are deeply rooted in this work.”

—Maya Moran ’21

Examples include the fact that URI now has a chief diversity officer, a post currently held by Mary Grace Almandrez. The University is undertaking a campus climate survey to help inform the next University diversity action plan. Another example is the successful College of the Environment and Life Sciences Seeds of Success Program, run by another former student activist, Michelle Fontes ’96, M.A. ’11.

Current URI student Maya Moran ’21 is working hard to make sure URI keeps the momentum moving forward. She is part of a group of students working with URI’s Office of Community, Equity and Diversity on a social justice series called Diversity Dialogues, which addresses issues of bias, microaggressions, and social identity.

Maya Moran ’21 is a psychology major and leadership studies minor and an undergraduate scholar in residence for URI’s Office of Community, Equity and Diversity. She is a co-creator of URI’s Diversity Dialogues project and vice president of the student organization D.R.I.V.E. (Diversifying. Recruiting. Inspiring. Volunteering. Educating.), which works with URI’s Office of Admission to increase diversity at URI.

Moran, who came from a diverse high school, says her initial experience as a student of color on a largely white campus included feeling like she was sometimes put in the awkward position of being an authority on race. “As if I were the spokesperson for all Black persons on Earth,” she says, adding, “We recognize that students are in different phases of awareness. Some are just learning about racism and microaggression, some know a little about these things, and some are deeply rooted in this work.”

For many of the activists involved in movements past, the racial reckoning happening in 2020 reminds them that the battle isn’t over. King’s words from his speech at URI more than 50 years ago still ring true: “We have gone a long way, but we still have a long, long way to go.”

Reflecting on the past and seeing the Black Lives Matter movement today gives Southern, Bakr, Forleo, and Oliveira hope.

“I was born in 1951. I saw and participated in civil rights activities and movements, and I have never seen the level of engagement and involvement by folks to advance a critical issue like today,” says Bakr. “To have that kind of movement take on the energy that it has, not only in this country, but in untold numbers of places internationally,” he pauses. “It’s totally unprecedented, totally unprecedented.” •

The Rev. Arthur L. Hardge and the Origins of Talent Development

The story of civil rights and the fight for racial justice at URI is incomplete without mention of Talent Development (TD) and the Rev. Arthur L. Hardge. “Rev. Hardge was an extraordinary man,” says Frank Forleo ’74, “A preacher, a storyteller, a leader.”

Hardge was a freedom rider with Martin Luther King Jr. He came to URI in 1969 as founding director of the TD program, to give underprivileged kids access to the state university.

“If you think about this time in context, Dr. King was assassinated and the civil rights movement was roaring through,” says Valerie Southern ’75, M.C.P. ’80. “At that time, the University was desperately behind, which is why Rev. Hardge started the program.”

The program that began with 13 students has grown to admit approximately 600 each year. And a large part of this growth is due to Rev. Hardge, the other founding staff of TD, and the belief they had in their students.

“They asked me to become summer director. I was young and didn’t necessarily think I was ready for that,” says Abu Bakr ’73, M.S. ’84, M.B.A. ’88, laughing. “But folks at TD were about giving people opportunities and allowing you to develop your talents. So that was my beginning, at age 23 or 24, of actually being in a director role. That’s what TD and Arthur Hardge gave me.” •

Photos courtesy URI Special Collections; courtesy Abu Bakr; Nora Lewis; Valerie Southern; courtesy Karoline Oliveira; courtesy Frank Forleo

I still remember the night of May 5 when the State Police came in. Not mentioned was there were as I recall 14 sent to the hospital that night. The State Police were wielding batons to beat their way through the students (supporting the Black students inside) who were blocking the path to the front door. I was one of the lucky ones I guess as I was on the left side of the door to Carlotti though yes it was still traumatic. But looking back no one in administration was listening and the students caused some good trouble that helped to wake URI up.

1998 Brothers United for Action (BUA) member…TD was our “home away from home” and encouraged us to stand in our truth!! URI’s Talent Development Program generated quality student leadership and we are now in roles throughout this country, clearing a path for this new generation of leaders!! (Thank you Rev. Dr. Hardge, Mr. Dimaio, Frank & Sharon Forleo, Ed Givens, Gerald Williams, BSLG and the many others of that URI era who shaped my professional trajectory!). “TD for Life!!!”

I arrived at URI Fall of ‘71 from NJ. Separated from May by those few months and a few hundred miles, I was not aware of the action until many months later. In Sept ‘71 this history was not being communicated to the larger community. No wonder progress was slow.

I recently received my Fall 2020 copy of the URI Magazine. The concept of memorializing TD in chronological order in a magazine such as this is an excellent idea. However, an accurate portrayal of the events that took place in the early years of the program is essential. As a member of that pivotal 1969 summer class (when Reverend Hardge and Mr. Leo Dimaio first joined forces). I was there for the next four years, graduating in 1973. I actively participated in all of the events that took place in 1971 described in the Magazine article written by Grace Kelly, however there are several glaring omissions and inaccuracies that need to be addressed. I knew all of the students involved and have a very clear recollection of the events that took place and those who participated in the 1971 student takeover of the Administration Building. However, to be sure that my memory hasn’t faded I contacted several of the students who were a part of TD, and were actively involved in the events that transpired.

One very significant point that needs to be included in any discussion of the events that took place at the Administration Building in 1971 is what Mr. Dimaio did when the State Police in full riot gear smashed down the door to the Registrar’s office that we were barricaded behind. I remember it well because it was terrifying. We were all lying on the floor with our arms interlocked and just when the police hit the door with a battering ram (or whatever they used) a photographer’s flash bulb went off. The room we were in was darkened and the effect was like a shotgun blast coming through the door – very scary. Anyway, the first person to enter the room was Mr. Dimaio, scurrying over the file cabinets and desks we had used for the barricade, shouting to the State Police Captain by name – “Don’t lay a hand on any one of my students in this room!!” As a result, not one of us was struck by the police that poured into the room wielding those long batons. It was total chaos but the TD students came out of it totally unscathed. Unlike the white students who supported our cause and were surrounding the outside of the building in a show of solidarity. Several of them got beaten up pretty badly.

My point in writing this is twofold. One – it is important that the facts surrounding this significant event in TD’s history are accurate, and two, with the passing of Mr. D. we need to be sure that his legacy reflects just how much he loved and protected his students from the very beginning. He was a unique individual who had a hugely positive impact on so many TD students – myself included, and his contributions should never be forgotten. Reverend Hardge use to frequently say “ that he and Leo Dimaio were joined at the hip, there was no one without the other”.

Daniel Price, Jr. ‘73