This year, URI’s Class of 1970 celebrates its 50th reunion. In early May 1970, just a month before URI’s graduation exercises, student strikes on college campuses across the United States, including at URI, were organized to protest the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. At Kent State University, the National Guard shot and killed four students during a protest. What was it like to be a college student during that complicated and uniquely transformative era? Class of 1970 alumni share their stories.

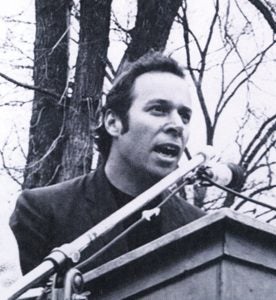

Dennis Lynch ’70 gave the student Commencement address in 1970. His address was insightful and powerful. He summarized the changes that defined the years from September 1966—when most of the Class of 1970 arrived at URI as first-year students—to June 7, 1970, when their graduation ceremonies took place.

“In these four years,” Lynch said, “things have changed. Our music has changed, our style of dress has changed, our lifestyle has changed, but more importantly, our minds have changed. These four years past have been the most blinding array of rapid evolution since this tiny sphere in the universe first began forming.”

Members of the Class of 1970 point out that it wasn’t always all about protests and resistance; there were still friendships, exams, football games, walks at the beach, romances, books, and all the other things URI alumni typically point to as hallmarks of their time here. But it was, by all accounts, a time of shockingly fast-paced social and cultural transformation.

Lynch’s characterization rings true today for members of the Class of 1970, who recall those years in the stories that follow.

From Order to Tumult

In 1966, we lived in a world defined by boundaries—parental and societal. We grew up watching TV shows like Donna Reed and Father Knows Best that reflected family life and the morals and values of the time. When I entered URI that year, we didn’t question authority and we complied with rules. Weeknight curfew was 10 p.m. No men were allowed in the female dorms—but if your dad was helping you carry in luggage, you yelled, “Man on the floor!”

But life began to change. As seniors, we had no curfew; men frequented our dorms. The scent of marijuana escaped from closed doors. Vietnam and Kent State changed us. We weren’t followers anymore. We went on strike.

In 1966, the campus was our orderly world. In 1970, the tumultuous world was our campus.

— Marilyn Conti Zartarian ’70

Best/Worst of Times

It was the best of times. Finally free from the cultural restraints of first- and second-generation parents, we were able to explore academic, social, and multicultural opportunities. When we began at URI, we had to wear skirts to the dining halls and even classes. By the time we left, we were wearing jeans or Army surplus clothes

every day.

It was also the worst of times. Rallies against the war were regular occurrences on the Quad. Friendships were strained, young men left for Canada; some left for war. Names of those killed were relayed in hushed tones. No one was without an opinion. Finally, the University was shut down just prior to graduation. Sadness, black armbands, and anger permeated among the smiles of our parents. We were ambivalent about our futures.

— Janice DiLorenzo ’70

Voice of Change

They called us “Baby Boomers” because of the uptick in births following World War II. Most of us had relatives who had fought in the war. For many, the war formed the basis of our beliefs about our government. During the 1960s, students generally went with the flow. It was a period of perceived “student apathy.” Gradually, students began to question some of the nation’s policies. There was a developing concern about social responsibility. The “silent majority” was in contrast to vocal activists. The voice of reason became clouded by the voice of change. Not everybody understood everything. The correctness of our role in Vietnam was still a point for discussion.

URI could never be confused with Berkeley, but Kent State and the Cambodian invasion changed many minds and yielded a focus. URI’s participation in the student strike (unthinkable just a few years earlier) was a result of that focus.

— Allen Divoll ’70

"Our music has changed, our style of dress has changed, our lifestyle has changed, but more importantly, our minds have changed."Dennis Lynch ’70

Becoming Activists

Those days between 1966 and 1970 held many changes. As college students, we seemed destined to participate. In the beginning of my sophomore year as a member of the Student Senate, I was asked to represent URI at the Associated Student Governments’ Conference in San Francisco. The conference was held during Thanksgiving break and the planners thought Thanksgiving dinner for students from across the country should be held at the Playboy Club. During the next two years, conversations and awareness changed. Activism nationwide concerning civil rights, women’s rights, and the Vietnam War became part of campus life and many of the old rules were questioned. We would not be going back to the Playboy Club in the years to come.

—Dianne “Dede” Davis Berg ’70

Closing it Down to Open it Up

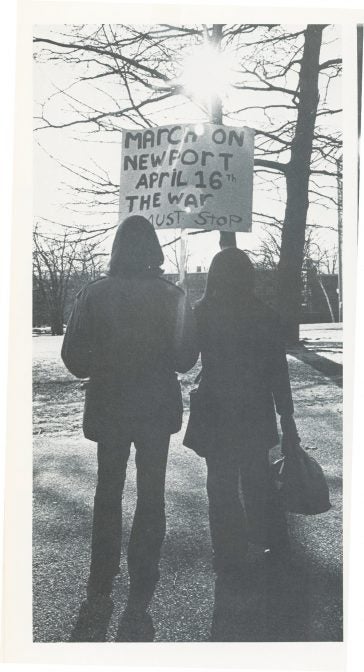

The University of Rhode Island had never exactly been known as a hotbed of radical politics. But on the morning of Friday, May 1, 1970, readers opened the campus newspaper, The Beacon, to find clear evidence that Bob Dylan’s 1964 anthem, “The Times They Are a-Changin,” still rang true.

“49,024 Have Died in Vietnam,” the top headline reported. The only other headline on the page read, “Student Senate Supports Strike.”

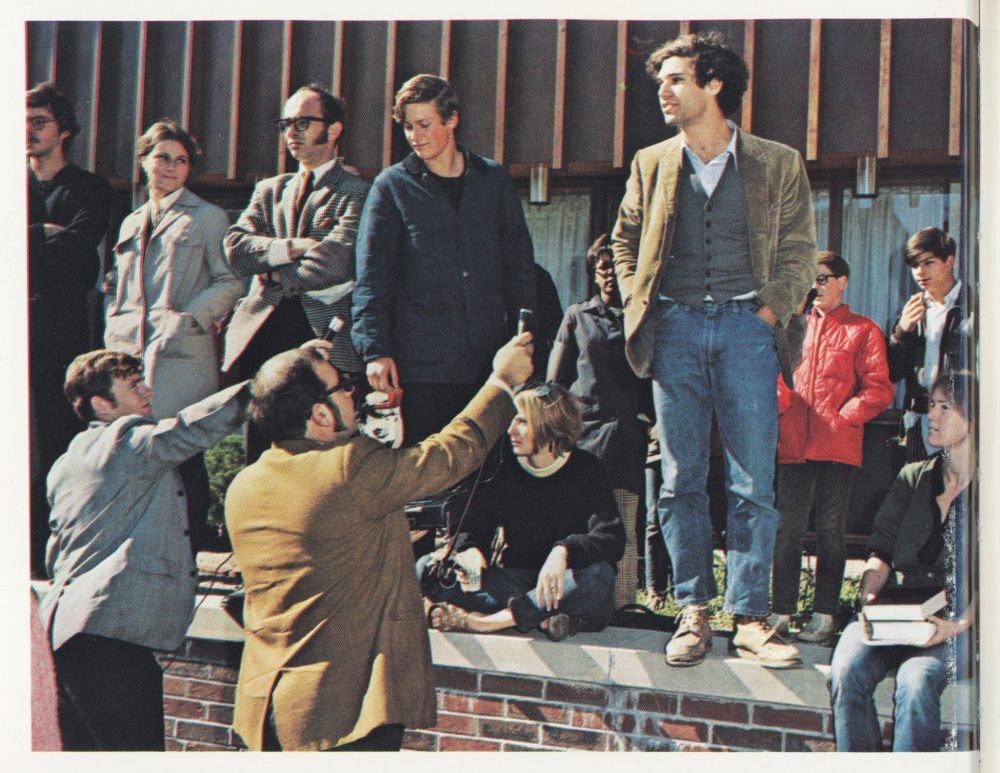

That day, students and faculty held an emergency rally on the URI Quad to call for a stoppage of classes the following Monday. The immediate purpose was to protest President Nixon sending troops into Cambodia and the death of four students on the pastoral grounds of the Kent State campus. URI joined a group of 175 universities and colleges from across the U.S., becoming one of the first schools in New England to join the strike.

On Tuesday, May 5, an overflow crowd, primarily students, packed Edwards Auditorium and almost all endorsed the strike. We adopted the slogan, “Close it down to open it up,” referring to our aspirations for the URI strike: opening our minds and hearts and broadening our perspectives through workshops and discussions on a variety of topics, such as how biological warfare affects civilian populations and the health of our planetary home.

The faculty senate concluded, after some heated discussion, that no student would be penalized for taking part in the strike—or not. Students were permitted to complete the spring term in the way they believed would be most beneficial personally and to the broader community. The principles of equality and freedom of choice prevailed.

—Art Stein, Professor Emeritus of Political Science

Professor Stein started teaching at URI in 1965. His former political science colleague, Professor Emeritus Al Killilea, says, “Art is a gentle and thoughtful man,” who, in the turbulent late 1960s and beyond, earned the respect of colleagues and students alike.

In 1999, Stein was one of the co-founders of URI’s Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies, and his committed approach to active social justice has continued unabated over the past half-century.

Transformed Forever

As a URI freshman in September 1966, I recall Labor Day weekend being filled with excitement. My parents moved me into Peck Hall with just two suitcases, which held my clothing, sheets, towels, and toiletries.

Freshmen were required to wear beanies to distinguish us from upperclassmen. This rule, like many others, was just accepted. We could wear what we wanted to classes and daytime meals, but girls had to wear skirts or dresses for evening meals. Interestingly, our skirts were so short, our fingertips could touch the hems. Pants would have been more conservative. But we complied without question.

There was a curfew, after which the dorm doors were locked. There was one pay phone per floor, and anyone walking by was responsible for answering calls and finding the person needed. There was one TV in the downstairs rec room for the entire dorm, and boys were allowed to visit only in that space.

By our graduation in 1970, we were no longer the same students. We became protesters, and defied authority on many levels. The repercussions of the Vietnam War and Kent State had transformed us forever. And beanies were never part of freshman orientation again.

—Victoria Salcone Cataldo ’70

Rally in Washington, D.C.

November 15, 1969—the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. Five or six of us piled into a car and took off to attend this massive rally in Washington, D.C. We made a stop at my home in New Jersey where my parents graciously fed us and allowed us to crash for a few hours before we caught the bus to D.C.

It was a bright, clear, chilly November morning. The bus parked and we joined the crowds in front of the Washington Monument. I was overwhelmed. I’d never experienced such a mass of humanity. But I was also exhilarated—here we were, thousands of us, young and old, peacefully united in a common cause. It’s estimated that a quarter of a million people attended. Peter, Paul and Mary and Pete Seeger sang. Senators George McGovern and Charles Goodell, and Coretta Scott King spoke.

Later in the afternoon, a couple of us were resting near the National Archives when all hell broke loose. A small faction of protestors got violent and the police lobbed tear gas into the crowd. A wall of humanity surged toward us and we ran in any direction we could to get out of the fray. That finished us, and we made our way back to the bus. Luckily, we were all there. Eyes and lungs burning, we boarded the bus, then got back in the car and trucked on back to URI. We got back in the early hours of the morning, exhausted and happy.

Did we make a difference? No. Not at all. President Nixon vowed that the protests would not sway his decisions about the war. Later that month, he gave his famous (infamous?) speech praising the “silent majority” who, he claimed, supported the war. But for me it was, and will remain, a high point. For the first time in my young life, I stood up to my parents and the establishment and fought for what I believed in.

—Frederick “Rick” Strickhart ’70

War Changed Everything

Like a tsunami, the anti-war movement engulfed American campuses. In the spring of 1966, I visited URI to inspect my future campus. It was graduation weekend, and President Lyndon Johnson was receiving an honorary degree. Professor Elton Rayack, protesting the Vietnam War, was escorted off the podium by two University officials. Professor Rayack later became my advisor.

Until 1968, I believed in the inherent good will of government. The war changed everything and the government mistrust we felt engulfed most U.S. campuses like a virus. When the strike occurred in the spring of 1970, the protests effectively ended the last couple weeks of school. I was co-captain of the track team and was preparing for the Penn Relays. I remember Coach Tom Russell telling me that “none of the other athletes reported for practice.” I explained to Coach Russell the reasoning for the strike and told him I couldn’t let the anger I felt politically interfere with my relationships or responsibilities. My beliefs over the years have not changed.

We were the Baby Boomers, born to parents of the “Greatest Generation.” Our URI experience taught us to question the misuse of authority and power. Today’s political turmoil reflects past times. Protest, alienation, upheaval—perhaps there is nothing new. I often reflect on what Yogi Berra so eloquently stated: “It’s like déjà vu all over again.” •

—Bob Bolderson ’70

Wow, this was a wonderful article to read and brought me immediately back to some of the best years of my life at URI. Thank you for this poignant article. In 1970 I was a freshman at URI completely unprepared for what I saw, heard and experienced on campus.I entered URI as a young boy from Middletown, RI and before I graduated in 1973 I was transformed emotionally, intellectually, spiritually. Today I’m a healthcare administrator and a university professor in Worcester, MA ( Clark University) and I try to explain, upon occasion, what it was like to live on campus ( Phi Sigma Kappa)during that tumultuous time in history; its quite impossible to relay the visceral sense of what we all lived through from 69 – 73. It was remarkable and I would not want to give back a second of it. Thank you Rhody for what you did to help shape my perspective on the world.

What a marvelous article. I was especially pleased to read the comments of 2 of my Student Senate colleagues, Al Divoll and Dede Davis

Those were times that changed everyone’s life, which is just what is happening now with covid-19.

May everyone stay healthy and safe

I entered URI in September, 1966, as a member of the Class of ’70. Due to a change in majors, I didn’t graduate, until January 1971. I was a member of the Track Team, coached by Tom Russell. I was also a Co-Captain in 1970.

Those photos of the protests brought back vivid memories. Yes, the war was an ominous, black cloud on the horizon. I remember how distraught many of us felt with Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia.

Although I protested the war policies, my lifelong dream was to fly. I had always planned to learn to fly in the military. I was torn. I felt that the military was being misused. Like almost all of us, members of my family fought in WW2. My Dad was an 18 year-old kid, when he stormed Utah Beach, in Normandy, France, as an Army Medic, in June 1944. The horrors he saw are difficult to believe.

War was never glorified by my family members, who had served in actual combat.

I still wanted to serve and learn to fly. I went on to become a Naval Aviator. I never flew in Vietnam, but flew as a Cold Warrior from 1971 to 1981. This led to a 31 year, flying career, culminating as an airline captain, which had always been my goal.

It wasn’t always easy to see the total truth, clearly, through all the noise and emotion,in that scary spring of 1970. In spite of all the turbulence and fear, there was still joy, love, friendship, and tremendous personal growth to experience at URI. I made my share of mistakes, but I learned from them. MY college career at URI created many wonderful memories, that will last a lifetime! GO RAMS!

Well stated about Our college careers at URI, Brother Kelly !!

Thank you for your Service and Dedication!

Be safe and Stay Well in these ‘unsettling times’!!?

Always,

Peter A. Forte

This article brings back so many memories. As freshmen in 1966, we were required to wear freshman beanies to identify us as newcomers. We had to wear a jacket and tie to dinner in the dining halls. The Vietnam war was central to our thinking as males. I was reclassified 1A in the draft, 23 times. I had to constantly go to the draft board and prove I was still enrolled as a student. I was ordered to a pre-induction physical three times and came with 1 day of being drafted twice. In our senior year, the students went on strike. I can remember my friends being at the entrance of Kelly Hall and asking me to join them. I figured it would cost me graduation, but I joined. Classes were cancelled and I did graduate.

Now I am back at URI as a lecturer. The Coronavirus shut down is so reminiscent of the experience 50 years ago. I can only hope that today’s graduates will go on to have as wonderful a 50-year experience as I did.