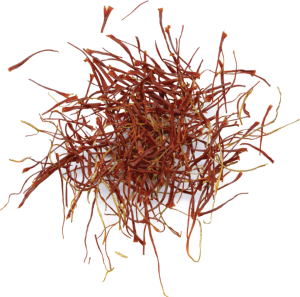

Saffron flowers bring spring to URI’s agronomy fields in October. Below right, the stigma of the saffron flower is harvested and dried to produce saffron, the world’s most expensive spice, which sells for about $5,000 per pound, wholesale. Demand for saffron in the U.S. is growing as more people from the Middle East and South Asia move here, and as appreciation grows for cuisines from those regions.

By Todd McLeish

An awakening of sorts is underway—at URI and across the globe. There’s growing recognition that the 20th century’s industrial approach to farming and food production is unhealthy for people, animals, soil, and the environment, and is environmentally and economically unsustainable. So what’s to be done? At URI, where agriculture is central to our history and mission as a land grant university, our faculty, students, and alumni are rediscovering our agricultural roots, taking a new, interdisciplinary approach to practical agriculture, and leading the way for a new generation of farmers and food producers.

In late October, a section of the University’s agronomy field is blooming with gorgeous purple saffron flowers. Although 90 percent of the global harvest of saffron—the world’s most expensive spice—comes from Iran, plant sciences professor Rebecca Brown has demonstrated that the Ocean State has the potential to claim a share of the market as demand grows in the United States.

“It’s tolerant of arid conditions, which is why it’s mostly grown in the poor, dry soils of southeastern Iran,” she says. “But until now, no one had tried to grow it in Southern New England’s moist, rich soils.”

With the help of postdoctoral fellow Rahmatallah Gheshm, who grew the spice in Iran for 27 years, last year’s campus saffron yield per acre was about triple that of Iran’s.

“It’s an attractive crop because you don’t need sophisticated farm equipment or technology to grow it,” she says. “It’s a lot less work to grow than vegetables, though it’s more labor intensive to harvest, which is why saffron is so expensive. It also doesn’t have insect or disease problems here, and you don’t have to water it. All of that is attractive to farmers.”

The saffron experiment is just one of URI’s many sustainable agriculture initiatives, which include numerous research projects, new faculty members, an academic major, and several campus measures designed to develop agricultural practices, products, and policies that reduce the environmental impact of food production while also considering economic sustainability and social justice for farming communities. The efforts attest to URI’s long history in agricultural research and education, and its commitment to leading a new generation of growers in an effort to create a sustainable system of food production.

How Can We Grow More Food in Less Space?

John Taylor’s initial polyculture studies focused on amaranth, a leafy green vegetable popular among African, Asian, and Caribbean cultures, and bitter melon, a warty, cucumber-shaped fruit with medicinal values favored in India and Southeast Asia. He is growing the two, along with a sweet potato variety grown for its leaves.

Plant sciences and entomology assistant professor John Taylor is looking for ways to produce more food in smaller plots by using different nutrient inputs and tillage strategies and by cultivating several crops in the same space in a practice called polyculture.

“In polyculture, you’re growing multiple species together to get more production from a unit of area compared to growing those crops in monoculture,” he says. “It’s a way to maximize the use of space. In Chinese-origin household gardens, they sometimes double production because they have a vine crop growing vertically on a trellis with a leafy ground layer below. It helps the household be more food secure.”

He is also teaming with the Southside Community Land Trust in Providence to evaluate the use of urban-adapted high tunnel systems, temporary greenhouses that help extend the growing season. By pairing raised beds in the tunnel with native flower beds that capture rain dripping off the tunnel, he is helping urban residents intensify production in small spaces.

“If we’re going to meet the goal of producing 50 percent of the region’s food needs by 2060,” as proposed in a report prepared in 2014 by Food Solutions New England, “then a lot of our food is going to have to come from small-scale production in urban backyards and vacant lots,” says Taylor, the first of several new professors hired as part of the sustainable agriculture program. He is finding that the yield from his urban farming experiments is much higher than production from conventional farms in Rhode Island.

An experienced farmer with degrees in horticulture and entomology, URI Cooperative Extension researcher Andrew Radin does outreach and consultation with the local farming community. Here, he shows local farmers a trellis system for growing tomatoes.

Cooperative Extension researcher Andrew Radin is also working to make the best use of high tunnels. “It’s like we brought a patch of North Carolina coastal growing conditions to Rhode Island,” he says. “It enhances productivity and makes things grow and ripen faster.” He is testing ways to improve production of tomatoes—the number one crop in high tunnels—by evaluating container mixes, calibrating nutrient requirements, and monitoring the occurrence of plant diseases and insect pests.

Envisioning the Future of Food Production

Sustainable agriculture research at URI doesn’t focus just on crops in the soil. Department of Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Sciences faculty members Marta Gomez-Chiarri, Austin Humphries, and Coleen Suckling are conducting studies of sustainability in the aquaculture and fishing industries, and Katherine Petersson, also in Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Sciences, is studying sustainable methods for controlling parasites in sheep.

And that’s just the food production side of the issue. Still other faculty are examining the topic from the perspective of economic sustainability, health, nutrition, culture, and communication.

Such diverse ways of thinking about sustainable agriculture made it ripe for the establishment of a new interdisciplinary major. Launched in 2016, the major in sustainable agriculture and food systems emerged as a result of requests from students for a course of study that combined food production with classes in business, health sciences, nutrition, policy, economics, hunger studies, and more.

“It also came about because employers and alumni said they want to hire people who have a broad education about food security, sustainability, and climate change and have diverse skills,” says Gomez-Chiarri, professor of aquaculture and coordinator of the sustainable agriculture major. “We had a lot of faculty doing sustainability in many departments, so we just had to package it in a way to provide the right guidance to students. The interdisciplinary nature of the program—requiring broad knowledge in the social sciences and the natural sciences—also means it’s a program that can easily be done as a double major with another discipline.

“More than anything, this major is about training students to have a vision of the future for what they want food systems to become and to make them understand the challenges of sustainability and getting big companies to buy into it,” she adds.

Students in the program choose one of three focus areas: food production, food and society, or nutrition and food. They are required to complete a capstone project and an internship, many of which are conducted at commercial farms or the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. Graduates might end up working in small- or large-scale food production on land or sea, finding innovative and safe ways to distribute and market food, or developing and enforcing policies that ensure food security and safety.

The first student to enroll in the program was Shayna Krasnoff ’17, who is now in the Peace Corps in Uganda, where she is an agribusiness advisor, training farmers in record-keeping, financial management, and related topics. She credits the major with providing her with the opportunity to explore what she described as “a budding interest” in sustainable agriculture.

“I’m passionate about supporting small-holder, regional farmers, both domestically and internationally, and helping them to stay ahead of trends in the food system and stay competitive in the market,” she says. “Through my Peace Corps service, I have seen the need for the development of supply chains that enable small farmers to easily meet the demand from buyers and receive fair market price for their produce.”

Where Theory Meets Practice

Jayne Merner Senecal ’02, with her father, Michael Senecal, who started Earth Care Farm in 1977. Jayne now manages the farm, which produces Merner’s Gold, a compost prized by local farmers and gardeners for boosting soil health.

URI alumni were employed in the sustainable agriculture field long before the academic major was established. Jayne Merner Senecal ’02 grew up in the industry. In 1977, her father started Earth Care Farm in Charlestown, Rhode Island, to produce farm compost, and now Senecal manages the farm, which uses sustainable practices so the land remains healthy for future generations. The compost she produces—known around Rhode Island as Merner’s Gold—increases the biological activity, drought tolerance, and nutrient density of the soil to which it is added.

“Lots and lots of carbon can be captured and stored in the soil through the simple process of building soil health by adding compost,” she says.

Most of the efforts to make agriculture more sustainable in Rhode Island are guided by Ken Ayars ’83, M.S. ’86, chief of the state Division of Agriculture, who works with partners to develop policies and programs to perpetuate local farming.

“That means, among many things, focusing on local sustainable food systems, connectivity between farmers and consumers, ecologically balanced farming, and all that is necessary to keep agriculture viable within Rhode Island and New England,” he says, noting that the growing interest in sustainable agriculture emerged from the region’s reliance on imported food, the increasing awareness of the ecological benefits provided by healthy farmland, and a growing desire to know where our food comes from.

Many alumni are joining the effort.

An Enlightened Food System

Matty Gregg ’09 owns Forty North Oyster Farms on Barnegat Bay in New Jersey, where he is helping to bring oysters back to the Mid-Atlantic coastal ecosystem.

In Cranston, Rhode Island, Corey Confreda ’14 is helping to make his family’s farm—one of the largest in the state—more sustainable by installing swales—shallow channels around growing areas to capture water and reduce fertilizer runoff—and by planting a cover crop between the rows to capture even more water, among other strategies. “We take farming sustainability seriously,” he said. “We try to implement new methods each year to reduce our impact on the environment.”

Matty Gregg ’09 owns Forty North Oyster Farms in New Jersey, where his shellfish operation filters the water in Barnegat Bay, provides nursery habitat for fish and crabs, and offers places for marine life to hide from predators. Along with his URI roommate Scott Lennox ’06, he also established the Barnegat Oyster Collective, a multi-farm organization that accounts for half of all farmed oysters in New Jersey and was featured in the award-winning documentary The Oyster Farmers.

“Economic sustainability is equally important to any viable business,” says Gregg, who was named a Small Business Innovator of the Year in 2017 by The Asbury Park Press. “Our strategic geographical location between Philadelphia and New York allows us to sell in those markets with a smaller carbon footprint. Most of that carbon [produced by transporting our oysters to market] is negated through carbon sequestration, a product of growing oysters en masse.” Oysters, which use carbon to make their shells, permanently remove carbon from the ocean and the atmosphere. Adds Gregg, “Every dollar we make is reinvested in growing more oysters and removing more carbon.”

In Rhode Island, Perry Raso ’02, M.S. ’06, owner of Matunuck Oyster Farm, was a finalist last year for the first New England Leopold Conservation Award for business owners who inspire others with their dedication to ethical land, water, and wildlife habitat management. Raso preaches not only a farm-to-table philosophy, but also pond-to-plate, as he supplies his oysters to his restaurant, Matunuck Oyster Bar, and grows much of the produce served there.

“As farmers, it’s no longer our job just to come up with innovative ways to grow our product,” he said in a recent speech at Providence’s Business Innovation Factory. “We also must engage in dialogue, education, and even conflict in order to meet our goals and in order to create a more resilient and self-reliant food production system.”

URI’s sustainable agriculture program is doing just that. By reflecting on the University’s founding as an agricultural college and recognizing the growing importance of creating a more enlightened food system for the future, it is educating a new breed of agriculturist and developing improved methods of food production to ensure food security for all. •

From the turf fields to the dining halls, URI is reaching out to showcase its agricultural expertise in a variety of ways, beyond our academic programs and faculty research.

In January, URI’s Business Engagement Center hosted the fourth annual Food System Summit, a gathering of hundreds of government, academic, and business leaders for discussions about how to better support the state’s increasingly important food economy. This year’s event featured conversations about how climate change is affecting the regional food supply.

According to BEC executive director Katharine Flynn, the first Food System Summit generated the idea of establishing a Food Center on campus, a resource center where farmers, growers, producers, distributors, servers, retailers, and others can easily access URI’s agricultural resources, food expertise, researchers, and business support programs. It will also provide students with unique opportunities to network with the sustainable agriculture industry and gain practical experience in the food sector.

The Food Center will be housed in the former turfgrass research building on Plains Road beyond the athletic fields and will contain conference rooms, office space, the Cooperative Extension’s Plant Protection Clinic (which helps community members identify pest insects and diseases on their plants), and a vegetable washing station where food grown on campus can be washed to meet food safety standards.

The University’s newest agricultural initiative is the creation of an Agricultural Innovation Campus on 50 acres at Peckham Farm, to include more than 25 acres of greenhouses and a 15,000-square-foot Agriculture Innovation Center, which will be URI’s hub for agricultural innovation, entrepreneurism, internships, and education. The campus will be developed in partnership with Rhode Island Mushroom Co.; American Ag Energy Inc.; Verinomics, Inc.; and VoloAgri Inc.; with startup funding allocated from a state bond approved by voters in 2016.

URI Dining Services is also doing its part to contribute to the University’s sustainable agriculture efforts. It’s partnering with local farms, fishers, and vendors to make “eat local” more than just a catchphrase, and its food waste is converted to compost through a partnership with the Compost Plant, a Providence business focused on diverting organic waste from landfills to high-quality compost. URI’s Dining Services is even growing herbs, salad greens, and tomatoes in the dining halls to reduce procurement time and product costs.