URI’s fifth annual Research and Scholarship Photo Contest attracted a stunning collection of photos from URI students, staff, and faculty.

The contest provides a unique opportunity for URI’s researchers and scholars to convey their ideas and work, as well as their unique perspectives, through the photographs and digital images they capture.

The annual contest is co-sponsored and coordinated by University of Rhode Island Magazine; the URI Division of Research and Economic Development magazine, Momentum: Research & Innovation; and the Rhode Island Sea Grant/URI Coastal Institute magazine, 41°N: Rhode Island’s Ocean and Coastal Magazine. A panel of judges, which includes URI alumni and staff, selects the winning images.

This year, for the first time, all our winning photos were from URI students—both undergraduate and graduate students, and all our winning photos were from work being done in the same college, the College of the Environment and Life Sciences.

The stunning photos reinforce that time-tested adage: “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

Winning photographers are listed below, with descriptions of their photos.

FIRST PLACE

Water Collection of a Honeybee

Casey Johnson, graduate student in plant sciences and entomology

“In the heat of summer, honeybees can often be found collecting water from puddles, gutters, and other unsavory sources,” says Johnson, who is a graduate student in Professor Steven Alm’s lab at the URI Agricultural Experiment Station at East Farm in Kingston, R.I. She continues, “We noticed that our honeybees were drinking water from sphagnum moss in the pots of pitcher plants, which led us to investigate the water-collecting behavior of honeybees on four local moss species. Here, a water forager honeybee rests on one of our observational moss setups, drinking water that she will bring back to her hive.”

SECOND PLACE

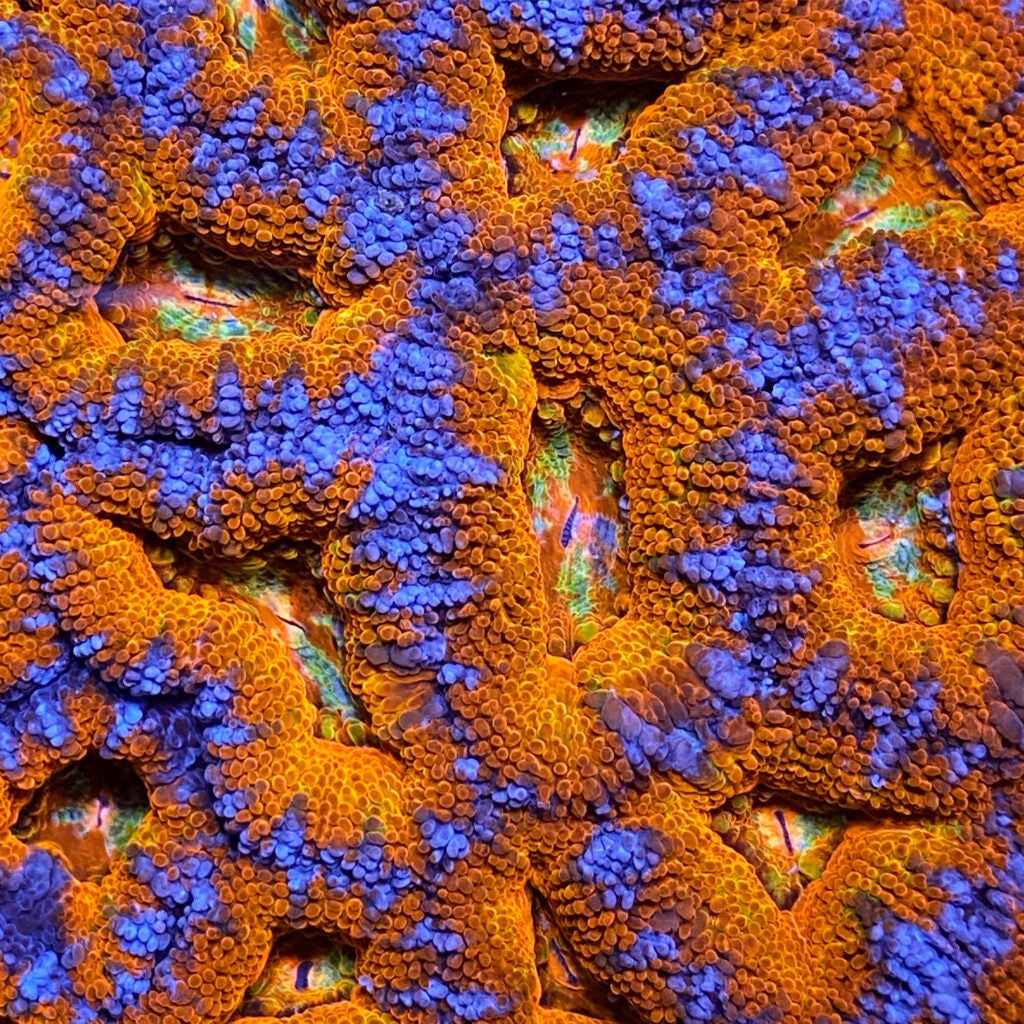

Jam-Packed Micromussa

Michael Corso ’24, aquaculture and fisheries science major

“This Micromussa lordhowensis coral colony was shot at Love the Reef, a marine animal distributor/coral aquaculture facility in Wilmington, Mass., where I work,” says Corso, who aspires to preserve tropical marine species. He continues, “In the wild, this species is found in the South Pacific and along Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. The bioluminescent colors emanate from the coral’s symbiont algae, zooxanthella. Rising ocean temperatures and acidification can prevent the corals from holding onto the algae they depend upon, resulting in coral bleaching. Land-based sustainable aquaculture efforts may be the last chance coral species like these have at surviving in our future environment.”

THIRD PLACE

Piping Plover Chick

Branden Costa, graduate student in environmental science and management, focused on conservation biology

Costa observed this juvenile piping plover foraging after a rainstorm on Washburn Island (Mass.). “These birds,” says Costa, who studies migratory bird behavior and population dynamics “are vulnerable to many threats before and after hatching, including predation, desiccation, human disturbances, and storm surges. They begin foraging for themselves mere hours after hatching and remain flightless for 25–30 days as they develop flight feathers for end-of-season migration. This chick was the last surviving member of its brood. The others were ‘taken’ by two off-leash domestic dogs. This chick demonstrates the unwavering resilience piping plovers must exhibit to survive.”

HONORABLE MENTION

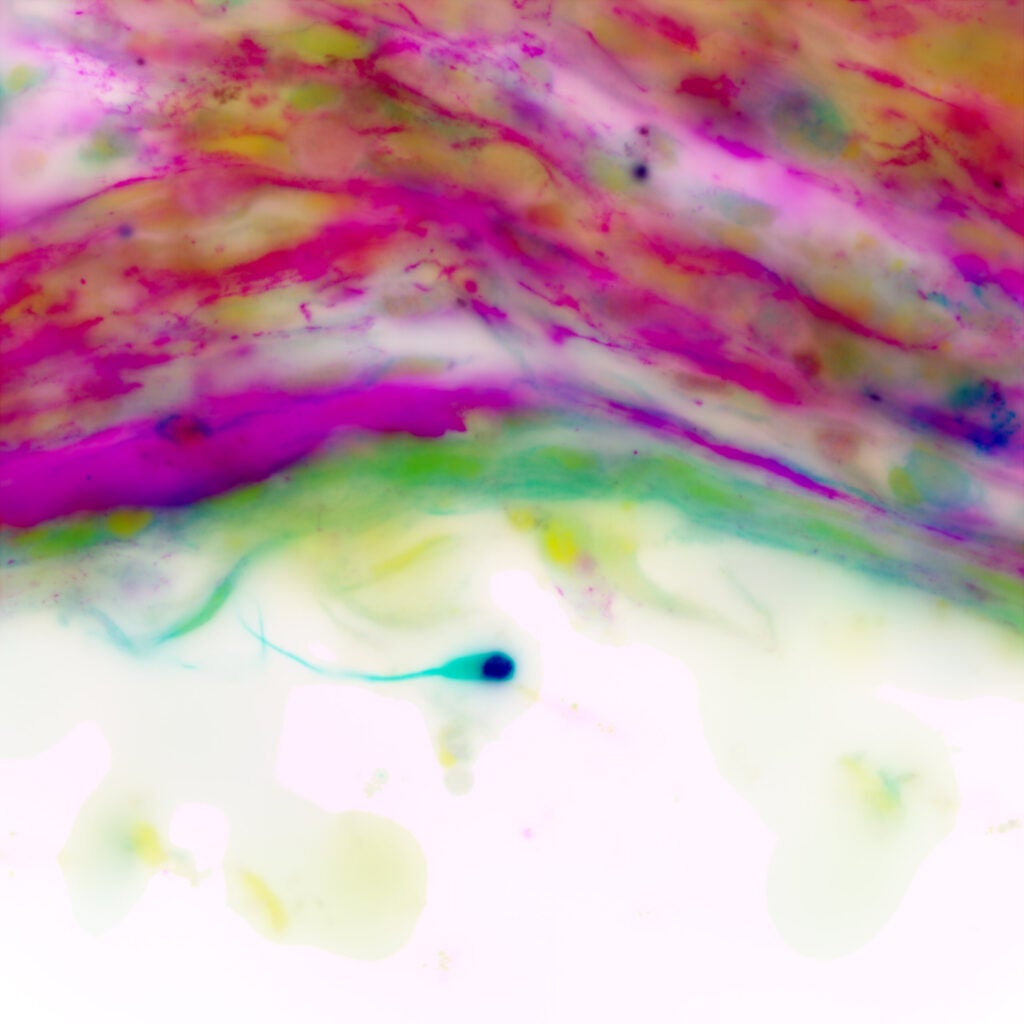

Last Nerve

Michelle Gregoire, doctoral student in cell and molecular biology

Nerves relay sensory or motor information in the body and are made up of nerve cells, or neurons,” says Gregoire. “In Professor Claudia Fallini’s lab, where I do my research, we study cellular pathologies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia (ALS/FTD). We differentiate the neurons we study from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), derived from patient skin or blood cells. Using immunofluorescence and our Leica DMi8 Widefield Fluorescence microscope, we visualized this stunning motor neuron. During the differentiation process, not all the stem cells differentiated into neurons, instead forming a mass of cells, visible here above the lone neuron.”

HONORABLE MENTION

Radiotagged Diamondback Terrapin Hatchling, Spring 2021

Carolyn Decker, graduate student in natural resources science

“This nine-month-old, rare salt marsh turtle is about the size of a poker chip and has just emerged from the secret sandy burrow where he spent his first winter,” says Decker. “For my master’s thesis, I documented the movements and habitat use of this species. This individual turtle helped us better understand the differing needs of hatchling and adult terrapins. My observations helped us to make wildlife management and conservation recommendations to protect the animals at all ages. This photo shows the tiny radio transmitter that was glued to the terrapin’s shell so researchers could track his movements.”

HONORABLE MENTION

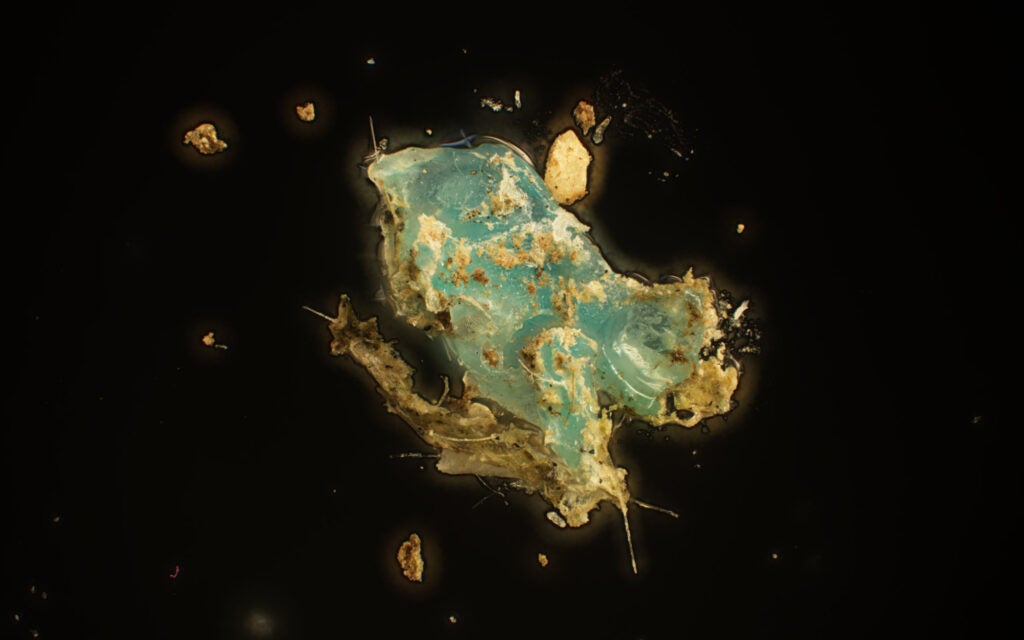

Microplastic Particle from Narragansett Bay

Sarah Davis, doctoral student in biological and environmental sciences

“This strangely beautiful image of a 1 mm microplastic particle was captured with an Olympus BX63 automated light microscope,” says Davis, who works with Professors Coleen Suckling and Andrew Davies on a Rhode Island Sea Grant project investigating microplastic particles in Narragansett Bay. “For this project,” she says, “we trawl a plankton net behind a URI vessel. The net collects material floating on and just below the water’s surface; the material collected is processed and analyzed in the lab. By studying the concentration and characteristics of microplastics in our local environment, we can help inform decisions about mitigating pollution at the source.”