By Arnie “Tokyo” Rosenthal ’73

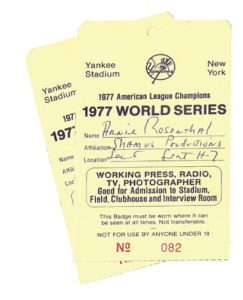

Assigned to cover a Yankees game for a local cable channel in 1977, Tokyo Rosenthal was excited to go to a game for free. He discovered that with his press pass, he’d been handed the keys to the Yankees kingdom. He would return to the stadium again and again for almost a decade, weaving an incredible story and capturing baseball history on film.

In the summer of 1958, I entered Yankee Stadium for the first time. I was

6 years old. My dad, a “Bronx Boy,” dressed me in a mini-Yankees uniform, which I didn’t take off for days. Seeing the stadium in color for the first time (we had a black-and-white TV) was overwhelming. I’d never seen anything that green before—and haven’t since.

Ten years later, on Memorial Day 1968, I was back at Yankee Stadium for a doubleheader. That day, Mickey Mantle played what many consider his last great game. I was invited by my friend, Jerry LaMonica, to sit in the press box. His uncle was the stadium’s ticket manager. Jerry and I made the long trek by bus and subway from Long Island up to the Bronx. Mantle hit two homers, two doubles, and a single, as he went five-for-five in the first game. Manager Ralph Houk gave Mickey Game 2 off.

Above: That’s me with Roger Maris (left) and Mickey Mantle on opening day at Yankee Stadium, 1978. I looked down the tunnel next to the dugout and there they were. I was instantly 10 years old again, the age I was in 1961 when they both ran after Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record. With total disregard for the circumstances, I told a newfound photographer friend that I was going to stand between Mickey and Roger and he had to shoot a picture. Mickey gave me a harsh look when I asked if he’d pose with me, and basically looked away. I’m down a step from them so I look like Woody Allen with my idols.

As James Earl Jones said in Field Of Dreams, “Baseball has marked the time.” And as the next decade passed, it marked my time, as well. The Mets went to the World Series twice, and the Yankees had been in a playoff drought of biblical proportions.

It was 1977. I had finished college and was getting my master’s degree in visual and communications arts. A new phenomenon—cable TV—was sweeping the nation. Public access television allowed amateur producers and directors to turn pro overnight. I was honing my videography skills at Manhattan Cable and any other video facility that would have me when I was asked to direct a weekly talk and news show called Sports ’77, hosted by a college kid named Bobby Leeds. One day, Bobby called and asked me to join a crew taping interviews on the field at Yankee Stadium. “Meet me at the press gate,” he said.

I thought it would be a one-time opportunity, and I was going to make it the best night of my life! A lifelong memorabilia collector, I intended to bring home anything that wasn’t nailed down. I shoved loose baseballs into my lens case. Paul Blair broke his bat during batting practice and tossed it aside; soon it was under my arm.

After batting practice, we left the field and assembled at the press box— land of unlimited free hot dogs, Carvel, soda, and, arguably, the best seats in the house. We were parked in the auxiliary press box—a euphemism for the least important press. But as I sat down, directly to my left and separated only by a plate glass window was “The Boss,” George Steinbrenner, in his private box. If the view was good enough for him, it certainly was for me, too.

I don’t remember the ride home that night; I’m fairly certain I floated back to Long Beach, New York, where I was living that summer in a rented cottage. I was thinking about how to describe the entire event to my father. And how I would tell my grandchildren about the time I went on the field at Yankee Stadium. After all, when would I ever get to do this again?

Ten days later, Bobby Leeds called again and asked if I’d bring the crew. He would be out of town and a substitute host would conduct the interviews. What he told me next would change my daily routine for years to come: how to get free press passes for the crew.

“For me, this was like knowing how to part the Red Sea. Could it possibly be this easy?

He said to call Anne Mileo, assistant to the head of media relations, tell her I was with Sports ’77, and that I would like to bring a crew to the game for interviews. For me, this was like knowing how to part the Red Sea. Could it possibly be this easy? Would she want to know more about the show? Who we wanted to interview? My blood type?

But it was the shortest phone call in my soon-to-be-long broadcasting career. Before I could finish my request, she cut me off and said there would be four passes at the gate. I imagined getting to the gate, finding no passes, and begging to speak to Anne Mileo, who would be out ill that night. But it worked, smooth as silk, and we were on the field again.

I wasn’t as boisterous this time and I don’t remember pilfering anything. I thought this would be my swan song, as I knew Bobby would soon return to school and the show would be canceled. But, I started to think, could the show live on, if only in the minds of myself and Ms. Mileo?

I began to ask myself if anyone actually watched Sports ’77. Or, more importantly, did any members of the Yankees watch it? Even more importantly, did Anne Mileo watch it? I began to hatch a plan.

What if I only wanted two passes this time? I could say our budget was tight and we were just shooting some stills to go along with the stories. It sounded plausible. What’s the worst that could happen? She could say no. Or call my bluff. Or she could say, “There will be two passes waiting for you at the press gate.”

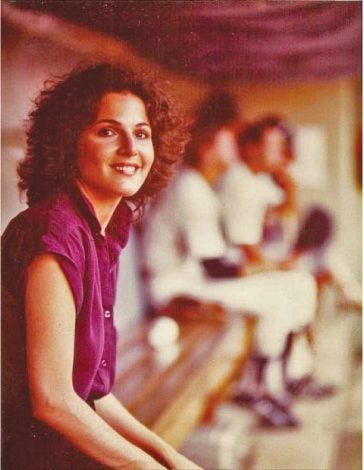

With my girlfriend in tow as the still photographer (she had a Nikkormat camera and some knowledge of how to shoot it), we picked up the two passes at the press gate.

My girlfriend—and future wife—Carrie Klein, was—and is—very attractive, and I worried she might create a stir with the players. Meanwhile, her instructions were to get pictures of me talking to the players. I looked professional with Carrie along playing the role of photographer. I was also spot-on about the players making a fuss over her.

“Can I get you some coffee?”

“Would you like some water?”

“Do you come here often?”

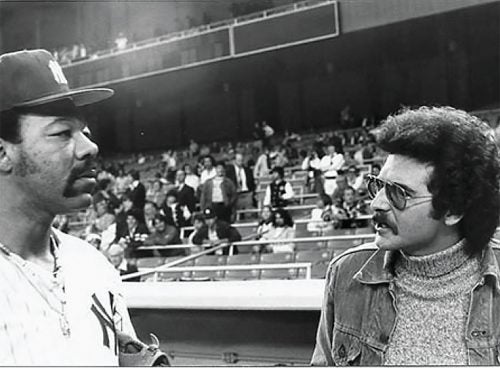

Suddenly I felt threatened; all these well-built guys in skin-tight polyester were hitting on my girlfriend. And what could I do about it? But once batting practice ended, their chance to fuss over her was over, and the rest of the evening went well. By night’s end, I had photos of myself with Yogi Berra, Graig Nettles, and Reggie Jackson—among others.

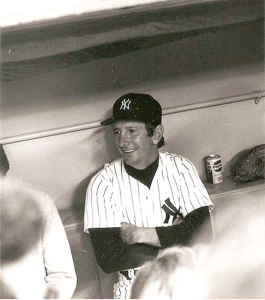

Enjoying Graig Nettle’s pre-game sarcasm.

In the dugout. Photo by Carrie Klein.

Carrie was flattered and having fun on the field, but she was bored silly in the press box. I don’t think we stayed until the end of the game, but the free Carvel kept her there for a spell.

Now, I thought, I had to get my father in on this. He had brought me to my first game, taught me Yankees history, and sat with me through the pennant-less drought of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

I had noticed that, except for the fuss Carrie attracted, no one was paying much attention to me. My very distinguished-looking father would be a striking figure on the field. He actually looked a lot like Steinbrenner. What if we got busted? But I calculated the risk and decided we could pull it off.

After explaining to Dad how it worked, I had the usual conversation with Anne, picked up my father in front of his factory on Madison Avenue, and headed north to the ballpark. Dad was dressed in a three-piece suit.

We drove around the Bronx for a bit, my father showing me his old haunts—where he played stick ball, where he once fell, and the famous building he lived in on the Grand Concourse with the fishes on the front wall. Then we parked at the ballpark and proceeded to the press gate.

Our passes were waiting for us. I whispered to Dad to just follow me. We made a sharp right down the old steel steps to the right of the press gate, and walked two flights down to the tunnel below the stands. Another right and 10 yards later we were at the crossroads.

To the right was the clubhouse, or locker room, which was still virgin territory for me. To the left was the tunnel to the dugout and the entrance to the field. We went left.

My dad found a spot behind the batting cage and took in the pitches one by one, amazed at the velocity from such a close vantage point. He attracted little or no attention. I was a four-time press box veteran; I figured everyone recognized me by now as a member of the working press—and famous producer of Sports ’77.

Nettles hit a walk-off homer to end the tied game, and we escaped to the car, two excited kids who had just gotten away with something special. I didn’t know then that my father only had four more years on this planet, so looking back, the night meant even more than I knew. It was, in fact, the last baseball game we ever attended together. But it wouldn’t be my last, not by a long shot.

The same year, I landed a job at a rehabilitation center producing “before-and-after” tapes of the center’s clients. I was also the in-house AV provider—slide shows, movie presentations, audio, etc. But they also wanted me to be a photographer and they had what, at that time, was a state-of-the-art Nikon with an assortment of lenses.

I figured I could learn how to shoot this camera on the fly, so I told them I knew how to use it. Fact was I had no clue. The only thing I could do was load the film—barely.

Reggie Jackson in the Yankee Clubhouse immediately following his 3-home-run game and the Yankee victory in Game 6 of the 1977 World Series.

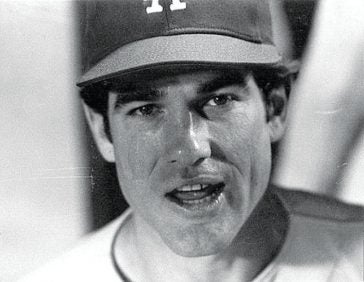

Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, prior to game one, 1977 World Series.

The Yankees made the 1977 playoffs. A quick call to Anne Mileo and 48 hours later I was sitting in the press box for the American League playoffs between the Yankees and the Kansas City Royals. Next to me was a Nikon camera just itching for me to learn how to use it. I was practicing a little, but I still didn’t really know what an F-stop was, nor did I know anything about depth of field, film speed, flash, strobe, or wide-angle. But I felt very legitimate with the camera around my neck and a case full of lenses.

The playoff games were televised nationally. Howard Cosell, Mel Allen, and Joe DiMaggio were there. I was beside myself. But I had a job to do: Shoot pictures—and see how they came out.

The five-game series would end with the Yankees winning Game 5 in Kansas City, so the locker room celebration pictures I aspired to shoot would have to wait. But I took pictures of the two games in New York. Some were sharp, in focus, well-lit. Others were blurry, poorly lit, blank, and poorly framed.

The Yankees would be playing Los Angeles in the World Series, so I was determined to get better at this fast. I also knew that eventually I would have to shoot something at my real job, which I desperately needed to hold on to.

To get the World Series press credential, it was the same easy process, except this time I picked up the pass at a midtown hotel.

On the field before the game, there were lots of celebrities. The easiest pre-game target was Dodgers’ manager Tommy LaSorda. He was so animated, and I managed to get some close-ups of him.

The Yanks split the first two games in New York, took two out of three in Los Angeles, and came home to close the show. I decided that, should they win, I’d make my locker room debut and get shots of the celebration. But I had no idea that I’d witness one of the greatest performances in World Series history as Reggie Jackson hit three home runs on three swings and the Yankees were world champions.

By the top of the ninth, I made my way to the locker room. I didn’t want to miss the champagne spray, and I was determined to witness and shoot the awarding of the World Series trophy. There was a line outside the clubhouse; the press wasn’t allowed in until the entire team was back.

When the team barreled down the tunnel and into the clubhouse, the champagne began to flow and spray. New York Mayor Abraham Beame awarded the trophy to George Steinbrenner, and the press was all over Reggie. My best shot of the festivities was one of Thurman Munson celebrating with coach Dick Howser, both doused in the bubbly.

The season was over, and my Yankee photographer career might have ended there, too. But I was already thinking about next season. So before the uniforms were dry, I called my favorite Yankee employee. The conversation went something like this:

Close play at home, 1978 World Series. Davey Lopes, Reggie Smith, and Thurman Munson. Note Smith helping the umpire make the call.

Arnie: “Hi Anne, it’s Arnie from Sports ’77. I just wanted to thank you for all the support.”

Anne: “My pleasure, Arnie. I trust you got everything you needed?”

Arnie: “Sure did. By the way, I hate to always bother you, so is there any way I could get a full-time pass for next year?”

Anne: “Shouldn’t be a problem. Just send me a letter requesting it during spring training down in Florida.”

1978, here I come!

I was back in the press box for the Yankees’ dramatic 1978 season, which ended with another Yankees World Series win against the Dodgers. I kept the job at the rehab center, and they even sent me to Nikon School for a crash course. I went back to the press box every year until 1984.

In late 1985, I found myself president of a national sports cable TV network. Now, I could legitimately have a press pass to any sports event in the world. Ironic, huh?

Yankee owner and “Boss,” George Steinbrenner, receives the World Series trophy, He is flanked by NYC Mayor, Abe Beame, and then-Representative, soon-to-be Mayor, Ed Koch. This is in the Yankee locker room, 1977.

Thurman Munson celebrates the 1977 World Series victory. That’s coach Dick Howser with a towel on his head in the foreground on the right. Future Braves manager Bobby Cox (he was Yankees first base coach in 1977) is on Munson’s left.

We had a steady stream of guests in our studios for live interviews. One day, boxing promoter Don King came by. Being a major fight fan and former amateur boxer, I visited the green room to introduce myself. After exchanging pleasantries with “DK,” I was introduced to his publicist, Joe Safety. His name was familiar. He said he’d been in Major League Baseball for years and had most recently been the head of media relations for the Yankees.

“My Yankees photos moved with me and Carrie from one NYC apartment to another, and then across the country and back. Most have been waiting to be seen for more than 35 years.”

I asked Joe if he ran the press box during his time with the Yanks. He said yes. I said I was sure he ran a tight ship, one in which no one who didn’t belong there ever got in.

He looked at me quizzically and nodded yes. And then I told him the whole story: Anne Mileo, the letters, the passes—everything. It was all very cleansing.

Joe asked for an outside line (if you’re old enough, you might remember those) and called Anne Mileo, who had recently retired. He repeated the story to her. She remembered me, the show—everything. They both found the whole story outrageously funny.

I don’t want my dishonesty, resourcefulness, or exploitative nature to shed any bad light on those I misled. They were all really nice people who I unwittingly took advantage of.

My Yankees photos moved with me and Carrie from one NYC apartment to another, and then across the country and back. Most have been waiting to be seen for more than 35 years.

I hope you enjoy them as much as I cherish letting them loose on the world. •

Editor’s note: This story is edited and excerpted from Rosenthal’s book, A Fauxtographer’s Yankee Stadium Memoir, which is available from Amazon Kindle. Rosenthal is a writer and musician who lives in North Carolina. His most recent book is Our Last Seder.

Photos: courtesy Arnie “Tokyo” Rosenthal.