By Ann Hood

Here is what we need to do. All of us. Right now. We need to stare out the window. Or go outside and lie on the grass and look up at the sky.

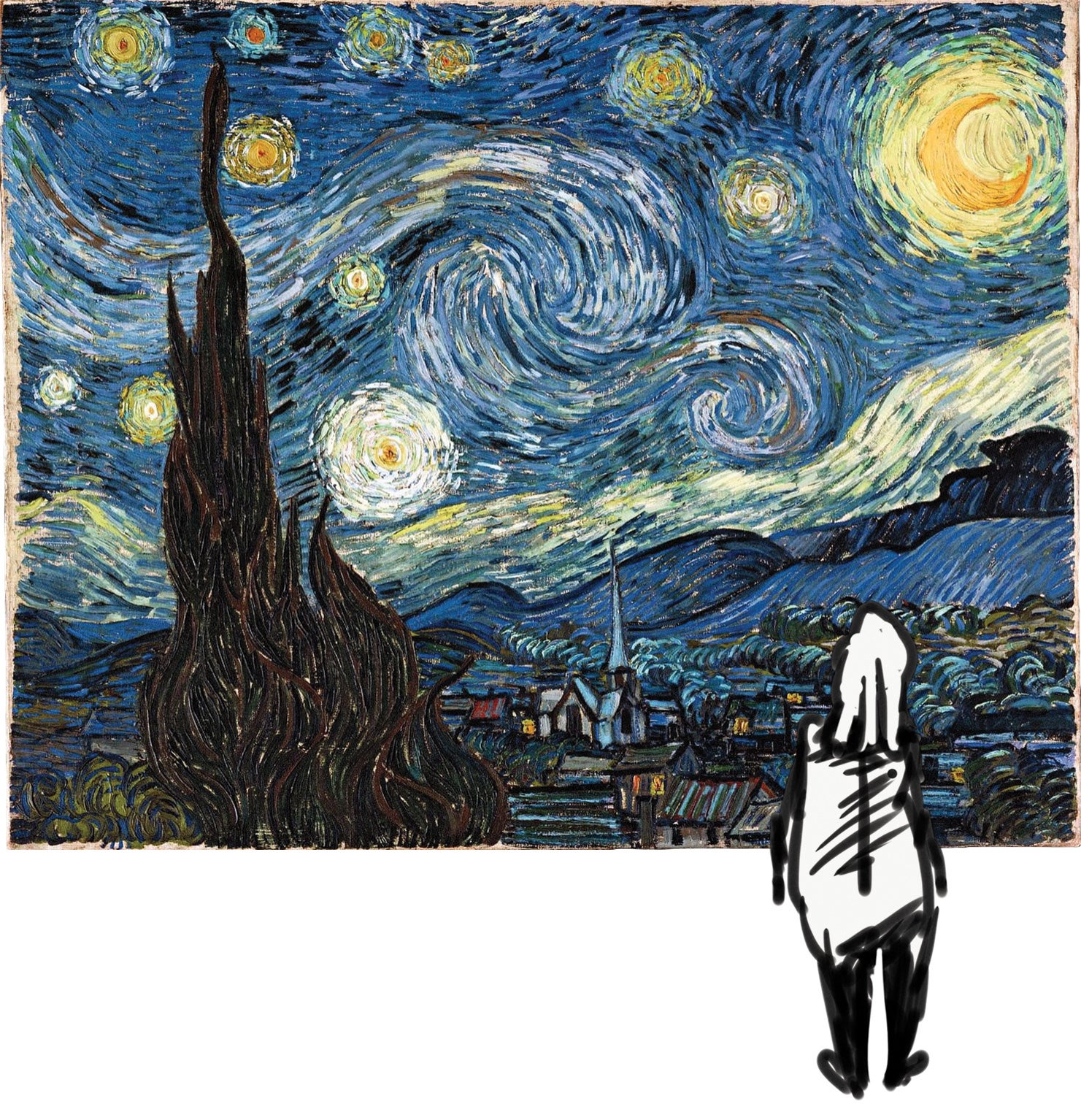

Perhaps you are rolling your eyes at this suggestion, wondering what good that will do us. Perhaps you have dismissed the idea already and are back to your to-do list or your applications or your phone or your project or any of the myriad things we fill every one of our precious minutes with. But let me tell you what can come of staring out the window. Very early one morning in 1889, a man woke before sunrise and lay in his bed staring out the window. “The sight of the stars,” he wrote in a letter to his brother, “always makes me dream.” That man was Vincent van Gogh, and staring out that window at those stars led him to paint perhaps his most famous painting, The Starry Night.

When I was 9 years old and singing along with the Lovin’ Spoonful on WPRO—And you can be sure that if you’re feelin’ right, a daydream will last along into the night—I had nothing to do but memorize the multiplication tables, read the Nancy Drew books in order, learn all the state capitals, and daydream. This was 1966, long before kids were overscheduled and fast-tracked. I didn’t do after-school activities (actually there weren’t any in my school), play on a traveling sports team, learn an instrument, or get enriched in any way other than through reading and using my imagination.

In high school—West Warwick High School, class of 1974—I acted in school plays and wrote for the newspaper and worked on the yearbook and had a job for Jordan Marsh that required weekly trips to Boston and weekends spent at the Warwick Mall handing out samples of Bonne Belle cosmetics and standing in the department store window in the latest fashions without moving for several hours at a time. As much as I am a fan of daydreaming, I am also a fan of being busy. Daydreaming for a thousand years, as John Sebastian continued in the song “Daydream,” does not get problems solved or children raised or legal cases settled or books written. About writing her award-winning short stories, Eudora Welty said, “Daydreaming started me on the way.”

It is this perfect balance of working hard, even very hard, and giving ourselves permission to daydream that we all need to strive for. “You know what I worry about?” Judy Blume, author of young-adult novels like Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret and Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing, said. “I worry that kids today don’t have enough time to just sit and daydream.” Even though Freud described daydreams as infantile and a way for us to escape real-life demands and responsibilities, I side with Judy Blume on the debate.

I arrived at the University of Rhode Island in the fall of 1974, that freshman who had practically run my high school and

suddenly found myself one of 10,000 undergraduates living in a coed dorm, confronted with offers of drugs, sex, and acts of

daring-do like climbing the tower on Route 138 in the dark, not to mention the slew of 8 a.m. classes followed by hours and hours of no obligations at all. I was 17 years old, and overwhelmed by it all, including having a roommate for the first time in my life. On my second morning at URI, I went to the bathroom at the end of the hall to take a shower. When I looked down, I saw the hairy legs and size-12 feet of the boy taking a shower in the stall next to mine, and I started to cry. It was all too much—Psych 101 with its 100 students in an auditorium, the stack of confusing course syllabi on my desk, the campus map—all of it was too much.

I finished my shower, went back to my room to grab the notebooks I favored back then—purple-lined pages—and practically ran down all four flights of stairs and outside, where I found a patch of grass beneath a tree. I sat down there. I didn’t even open my notebook, not right away. I just sat there and lost myself to daydreams. “Unlike any other form of thought,” Michael Pollan wrote in A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder, “daydreaming is its own reward.” It was for me that day.

I cannot remember where those daydreams took me, though surely far beyond Barlow dormitory and Psych 101 to some fuzzy future that involved Parisian garrets or glitzy Manhattan literary parties. But what I do remember is that after a little while beneath that tree, I opened my notebook and wrote a very bad poem that I probably thought was brilliant. Then I got up and walked back inside with the strength to face the day.

Although I can’t speak for the generations of college students that followed my own, I do know by having raised a son who is now 25 that the challenges facing them are even harder in many ways than the ones I faced in the mid-1970s. And one of the biggest of those challenges is being over-scheduled, with virtually every free minute after school taken up by activities geared toward achieving better grades, higher status, awards and internships, and fancier degrees. According to USA Today, studies show that over the last 30 years, children have seen their free time evaporate. They spend half as much time playing outdoors as kids did in the 1980s. And an American Psychological Association survey showed that 1 in 4 teens feels extreme levels of stress during the school year. Some researchers have even suggested that overscheduling and the growing pressures to succeed have caused a growing empathy gap. “Students entering college after the year 2000 had empathy levels 40 percent lower than students who came before them,” Vicki Abels wrote in that 2014 USA Today article, “Students Lack School-Life Balance.” She adds that a recent study at the University of Colorado found that students with unstructured time are far better at setting and accomplishing goals.

It may sound facile to believe that daydreaming can help counter these negative trends, yet Josh Golin, executive director of the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, says, “It’s important to let kids be a little bored and see what comes out of that boredom.” Golin advocates for the ultimate goal of a healthy mix of activity and unscheduled downtime. Alvin Rosenfeld, author of The Over-Scheduled Child, agrees. “Enrichment activities add a lot to kids’ lives,” he told The New York Times in 2013. “The problem is we’ve lost the ability to balance them with downtime.” Part of his solution? “Spend time with no goal in mind.”

After my own bumpy start to college, which included landing on academic probation after my first semester—a real blow to a straight-A student—I got busy. I won a seat on the Student Senate, became its Tax Committee chairperson, joined a sorority, took advanced Shakespeare classes, wrote notebooks full of bad poetry and short stories, went to plays and museums. But the busier I got, the more I made time for my favorite activity: daydreaming.

As much as I remember with great fondness listening to Dr. Warren Smith passionately discuss King Lear and Othello, I remember with equal fondness sitting on Narragansett Beach with my pals Kathy and Mary-Ann doing nothing at all. We talked about love and the big futures awaiting us. But we also stretched out on our blanket beneath a warm sun and just listened to the waves, our minds going in different directions, our dreams taking various shapes and journeys. I treasured, too, the long walk alone from Alpha Xi Delta on Fraternity Circle, all the way uphill to Independence Hall, a walk of almost a mile, with just my wandering thoughts for company. By the time I arrived at Dr. Smith’s class, I was ready to think and argue and discuss Shakespeare. From there I walked across the Quad to the Ram’s Den, where I always found a table of friends to join. How grown-up I felt when I bought a cup of coffee! How nourished I was to sit there for an hour or more deep in conversation. I would have to race off eventually, to a class or a meeting, fueled by not just intellectual stimulation but by camaraderie and the time to think my own thoughts in the most unstructured way possible—free-floating, free-associating, unconscious, necessary.

In his New Yorker article, “The Virtues of Daydreaming,” Jonah Lehrer writes about how psychologists and neuroscientists now believe that mind wandering is actually an essential cognitive tool. “It turns out,” Lehrer tells us, that when we daydream, “we begin exploring our own associations, contemplating counterfactuals and fictive scenarios that only exist inside our head.” And that’s good for us. “We think we’re wasting time,” Lehrer concludes, “but, actually, an intellectual fountain really is spurting.”

As I write this, I am in my apartment in Greenwich Village on a warm summer’s day. My husband is across the room at his desk working on his new book. I have a lunch meeting in an hour. During that hour I could read my students’ papers for an upcoming class. I could revise the new ending of my manuscript, or myriad other tasks and obligations. But instead, I will step outside into that sunshine and meander across town, just me and my thoughts. What a day for a daydream, indeed! How about you?