For these URI scientists, the ocean is their workplace, their playground, their sacred space. And their love of the sea is a net gain for science, engineering, and the environment. Maybe even humanity itself.

By Marybeth Reilly-McGreen

To hear Alexandra Moen ’15 describe it, seeing spider crabs molt is kind of like watching a Burning Man event underwater: It’s a large-scale spectacle. When spider crabs molt, they aggregate, climbing one atop another, creating mounds that can expand to nearly 100 meters long, according to BBC Earth’s Blue Planet II.

Moen witnessed the spectacle firsthand several years ago. While diving with her students in the waters off Taylor Point on the east side of Jamestown, Rhode Island, they came upon a molting. “What we saw was massive. Probably a 6-foot-tall ball of thousands of spider crabs,” she recalls. “They were shedding their exoskeletons for yards and yards. All visibility was taken up by spider crabs molting. It just blew my mind.”

It also provided Moen with a teachable moment beyond the scope of the day’s diving lesson.

“When you put yourself in an environment like that, you’re certainly connected with nature, and you develop a greater appreciation for protecting its resources,” Moen continues. “The connection we can create by bringing students directly into this underwater environment—I mean, there’s no better way to understand what’s going on.”

What exactly is going on?

“You see seasons underwater. You see this incredible fluctuation of productivity with life. In the winter, everything gets really quiet and you tend to have nicer visibility,” Moen says. “Come summer, nutrients in the water start getting a little heavier and your visibility goes down, but all of these things have grown and you start to see all these tiny, little baby fish darting out of the eelgrass in the shallows, and you’re like, ‘Ah, this is beautiful.’

“You also see balloons, empty chip bags, six-pack rings, and fishing line. It’s one of the greatest perks about my job that I can break that disassociation that we have—that what we do to the environment doesn’t matter,” Moen says. “I can show students that it does matter; I literally submerge them in an environment where they can see the effect of that thinking.

“The ocean is home to me. And as wild as it sounds, I’ve never been so certain about something in my life.”

—Alexandra Moen, URI Diving Safety Officer

“You just have to make the connection.”

In the book, Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do, author and scientist Wallace J. Nichols argues that people like Moen who’ve experienced “blue mind”—an at-homeness in the environment, in general, and the ocean, in particular—should share that experience with others—for the good of humankind and the planet.

“Our deepest, most primordial emotions drive virtually every decision we make, from what we buy to the candidates we elect,” Nichols writes. “We need to tell a story that helps people explore and understand the profound and ancient emotional and sensual connections that lead to a deeper relationship with water.

“The Blue Mind story seeks to reconnect people to nature in ways that make them feel good, and shows them how water can help them become better versions of themselves.”

Nowadays, Moen’s blue mind finds its expression in surfing as well as diving.

“What attracted me to the sport more than anything was how hard it looked. What better way to be both at home and to be challenged than surfing?” Moen says. “I am learning things every single time I paddle out. My god, does it humble me.

“But, I am a strong believer in the benefit of experiencing all of these things. In a world where everyday tasks are becoming simplified and less challenging, we are losing what it means to be part of something bigger than ourselves,” Moen continues. “Something we cannot control or simplify. For me that is nature, and, more specifically, surfing. It has helped me become more confident and proud of myself.

Pride, amazement, wonder, joy, happiness, peace, respect, awe, protectiveness: Such are the feelings and emotions URI professors and staff speak of when talking about their beloved ocean and the influence it exerts in their work—and lives—in ways big, small, and surprising.

Richard C. “Rick” Rhodes III figures he’s been surfing for 50 years, three to four days a week. “As frequently as there are waves,” he says.

How much does Rhodes love the ocean? Sit a spell. And fair warning: Surfing stories are like fish stories. With each telling they grow more epic.

Rhodes had just returned from a work trip to Morocco, where he’d surfed intense waves. “I returned to winter in Rhode Island and these puny, little waves about head-high in Matunuck,” Rhodes recalls. “A wave caught me right in the back and I started falling down. The wind caught my board and it hit my head.”

Rhodes blacked out. When he came to, he saw a trail of black in the water. Blood. Other surfers were yelling, asking if he was OK. Rhodes assured them he was fine and began paddling in. When he got into the car and caught a look at himself in the mirror, he was stunned. “I looked like I’d been in an axe fight.”

“Change starts with having a personal environmental ethic, and that ethic is to do no harm. Take care of what you have.”

—Richard C. Rhodes III, Executive Director, Northeastern Regional Association of State Agricultural Experiment Station Directors and former Associate Dean, Research, College of the Environment and Life Sciences

Rhodes called his wife, telling her he was headed to the hospital. He’d likely need a stitch or two—or so he thought. “In the ER, two nurses and the PA on duty were surfers. They said, ‘Wow, that’s so gnarly. How’d you do that?’”

He laughs, still amused that they were impressed. Rhodes’ injury was significant: a gash that ran from the bridge of his nose to the middle of his forehead, arching over his left eyebrow. It required seven stitches.

“But when I tell the story, seven stitches grows to 70,” Rhodes quips. “The worst day of surfing is better than the best of a whole lot of other things. Even if you get skunked, you’re still in the water.”

While he is quick to point out that he came to URI for his career—“The really strong attraction was the job”—Rhodes considers the Atlantic to be quite the job perk.

“What I enjoy is being able to tap that source and utilize the power of the ocean for pure, unadulterated fun. It’s unlike anything else. That thing that you’re riding is moving, and you’re moving in a different dimension, and that is the coolest feeling in the world,” Rhodes says. “The power of the ocean just surges under your feet.”

The up-close-and-personal relationship Rhodes has with the ocean has made him an advocate of scientific literacy; essentially he wants people to understand scientific concepts and processes so they can make informed and ethical decisions in their personal and professional lives, as well as at the polls. In his current job, Rhodes examines the way we raise food—and how much food we raise. Climate change, saltwater inundation in soil, nutrient-deficient land: These are just some of the issues we face in the near future, he says. And then there’s pollution. Every year, approximately 9 million tons of plastic waste enter the ocean, according to a May 2019 National Geographic article, “Little Pieces, Big Problems.”

How to change things?

“Change starts with having a personal environmental ethic, and that ethic is to do no harm. Take care of what you have,” Rhodes says. “We were taught as graduate students to be unimpassioned observers of science. But your job—as a scientist, as an educator—is to provide a context for data. You are also responsible for providing environmental literacy.

“We are all caretakers in this, and we all have a stake in this.”

Brian Caccioppoli ’11 came to URI to study marine biology as an undergraduate, but fell in love with coastal geology. He studies climate change, erosion, and other factors affecting coastal geography. He works with other marine research specialists and lab techs mapping shorelines and seafloor depth, and surveying the marine life there. Plainly put, Caccioppoli’s work monitoring and documenting change provides answers to such questions as why and how beaches are altered—by single events (like storms) and over time—which, in certain cases, places Rhode Island in a better position to seek federal funding. “What I do is pragmatic science,” Caccioppoli says.

“The ocean is an almost magnetic thing to people who are drawn to it.”

—Brian Caccioppoli, Marine Research Specialist, Graduate School of Oceanography

Pragmatic science can be disheartening. For instance, beach replenishment—adding sand to an eroding shoreline to reduce storm damage and coastal flooding—can feel futile because, says Caccioppoli, “It’s not unheard of for a beach to lose a third of replenished sand within just two years.” But Caccioppoli presses on. His stake in this work extends beyond the bounds of professionalism. “I want to know what’s going on and how it will affect what I love to do,” he says. “It’s all intertwined for me.”

What Caccioppoli loves to do is surf. He’s been at it for 14 years. Growing up on Long Island, he and his family were at the beach three to five days a week in the summer. Surfing was an instant addiction. “The first wave I caught, I knew I was in trouble. I knew it was going to change decisions I made on a daily basis,” he says. “The first time you get your feet on the board and catch a wave, it feels like you’re flying.

“When you go out into the water, your brain clears. You stop focusing on anything other than the pure experience of being on the ocean,” Caccioppoli continues. “Your burdens are gone. You come out and the tasks you have to do don’t seem so huge. It’s such a mood elevator, such a stress reliever.”

Yet surfing sometimes grants Caccioppoli an up-close-and-personal view of the tension that is climate change. One way climate change manifests itself, for instance, is in more frequent and powerful storms. Storms produce better surf. “But climate change could also result in the disappearance of some of our current surf breaks,” says Caccioppoli. “Quite a few local surf spots break best at lower tides—Matunuck, for example. We know sea level has risen over the past century here in Rhode Island. That trend will result in higher sea levels, which will inevitably result in changing surf breaks, possibly rendering some nonviable.”

In talking of his fellow New England surfers, Caccioppoli characterizes them as “fully committed” to the sport. In observing him talking about his research and his chosen sport, the phrase fits him, too. Caccioppoli smiles at the suggestion.

“The ocean is an almost magnetic thing to people who are drawn to it,” he says.

it herself: “I’m calmer when I’m surfing,” she says.

Photo: Michael Salerno

For the past nine years, Emily Clapham ’02, M.S. ’04 has directed a surfing program at Narragansett Town Beach for children with disabilities. She is assisted by student volunteers whose interests range from speech and language to education and kinesiology. The program—Catching Waves for Health, URI Xtreme Inclusion—serves children with varying degrees of abilities, including Down syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, cerebral palsy, and developmental delays. Surfing lessons are free for participants, and student volunteers can get college credit for their work. In Clapham’s near decade of experience, she has seen surfing and surf therapy have a positive effect on children’s physiological, social, and emotional responses. Clapham first noted such outcomes in her own mental, emotional, and physical health, and was eager to share the benefits with others.

“I know I have a clearer head on the water,” Clapham says. “I’m calmer when I’m surfing, when I’m experiencing the rhythmic motion of the waves.”

Clapham’s work has attracted attention and funding from such sources as the John E. Fogarty Foundation for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities, the Gronk Nation Youth Foundation, and the Doug Flutie Jr. Foundation for Autism.

“Children will stop and cheer for others when they catch a wave. They get excited for each other as they learn and grow together.”

–Emily Clapham, Associate Professor, Department of Kinesiology

And while the benefits are myriad for anyone who surfs—improvement in core and upper-body strength, cardiorespiratory endurance, balance, self-esteem, and confidence—for children with disabilities, these gains are amplified, and other gains are also apparent.

“Goals are focused around cognitive, physical, and social gains,” Clapham says. “Children will stop and cheer for others when they catch a wave. They get excited for each other as they learn and grow.”

Participants also aren’t held to a single right way to surf. Some kids want to boogie board, some stay in the white water. “One little boy wanted to sit on the board backward to watch the waves,” Clapham recalls.

One of the greatest accomplishments to be had for the kids Clapham works with is the sense that doing such a thing as surfing earns people’s attention and respect. “It is not an easy activity and takes strength, patience, and perseverance to be successful,” says Clapham. “The ocean can be very humbling.

“Surfing gives them street cred because they’re doing this cool thing—they’re surfers,” Clapham says. “They’re actually out there doing it.”

“I never really get away from my work. That’s how I operate—by being completely immersed. We’re trying to push the limits of the technology out there now.”

—Brennan Phillips, Assistant Professor of Ocean Engineering, Graduate School of Oceanography

Brennan Phillips ’04, Ph.D. ’16 is in the midst of packing up much of his deep-sea robotics lab—URI’s Undersea Robotics and Imaging Laboratory—for a trip. There is much to see and wonder at—hardware, electronics, 3D printers, and computers everywhere. Phillips and his group create complex machines—Phillips calls them “systems”—for oceanographic and deep-sea exploration. To the untrained eye, these systems look like little robots. With their low-light imaging systems, manipulators, and lightweight, low-cost technology, these units are affordable and well-suited for capturing images of remote, unexplored undersea environments. “We’re trying to push the limits of the technology out there now, much of which is big, heavy, and clunky. We’re trying to make it smaller and lighter,” Phillips says.

Photo: Courtesy Brennan Phillips

Phillips learned to surf as an undergraduate at URI. To hear him talk about it, surfing seems more another aspect of his education than simple recreation.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever tried to do. I had no idea how hard it was going to be. But I like to be challenged. The first day, I borrowed a board.” The next day, Phillips went to a local surf shop, bought a 9-foot board, and brought it home to Peck Hall.

“My junior and senior years, I got serious. It was like joining the mob,” Phillips jokes. “This is my sport. I run, ski, and bike, but surfing is my number-one favorite thing to do in the whole world.”

Phillips is a year-round surfer. “I like to be in nature. If you pay attention, there are days all year-round when there are waves. I aspire to get out once a week.”

Whether in or out of the water, Phillips thinks about how human beings might access the ocean without disruption. How might one of his small, lighted, bulldozer-like machines, for instance, take scientifically accurate photographs of the ocean floor when its very presence causes marine life to scatter?

Like his fellow surfing scientists, Phillips’ work and play intertwine. He talks of the day when all that goes into making underwater robots could be applied to tailoring fins or wetsuits. Already, there is an Australian robotics lab focused on surfboard design, he notes.

“I never really get away from my work,” Phillips notes. “That’s how I operate—by being completely immersed.”

Austin Humphries estimates he spent about 200 days on the water last year—nearly seven days a week from May to September and all of January.

An assistant professor of ecosystem-based fisheries science, Humphries took about 75 research dives last year and calculates he spent more than 100 hours underwater. “I interact and interface with the ocean on a daily basis. I fish, surf, dive, and sail.”

Humphries studies fisheries and coastal management in the United States, as well as in developing countries such as Kenya, Indonesia, and Ghana. He and his team collect data on fish populations, fishers’ catches, and where fish go and how that impacts livelihoods. To do this, they compare heavily impacted ecosystems with those that have less of a human fingerprint. With these data, they create simulations for fishery managers or fishers to use in decision-making. This could mean limiting the number of fish that can be caught in an area, or promoting a certain type of fishing gear.

“The fluidity of the ocean is comforting to me. The boundless nature of it. It’s amazing.”

—Austin Humphries, Assistant Professor of Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Science, Department of Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Sciences

“We look at the influence or ramifications of different management strategies and how those strategies translate into fisheries’ catches and well-being,” Humphries says. “It’s a challenge to work in places with poor infrastructure, but it can be incredibly rewarding and is often at the invitation of fishers and fishery managers. The first thing I do when starting a research project is go to the place and talk to people about what they want done. Then we build from there.

“They’re hard problems, and there’s never one answer,” he says.

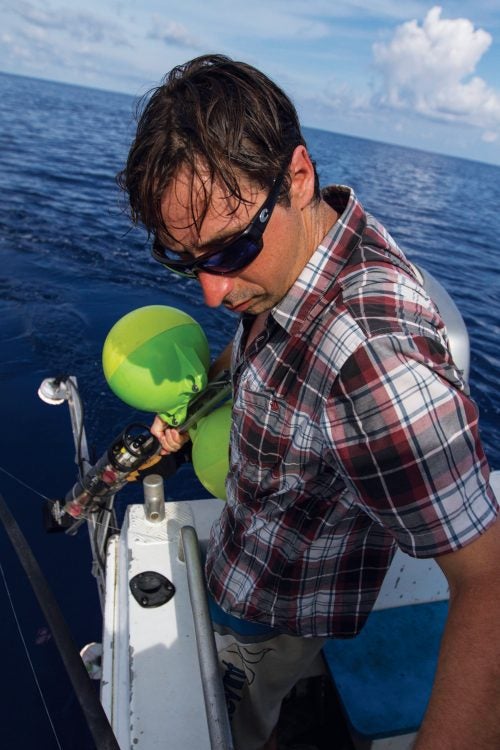

Photo Courtesy Abbyan Fairy

The work suits Humphries, a Virginian, who worked as a fisher in Alaska after graduating from college. “I recognize and sympathize with the plight of fishers. They face wicked problems.”

“Wicked” not in the Rhode Island sense, but as a descriptor of a problem that is difficult, if not impossible, to solve because of its interconnectedness with other problems. Still, you get the sense that Humphries is more than content to grapple with the impossible and that the sea has more than a little to do with it.

“The fluidity of the ocean is comforting to me,” Humphries says, “the boundless nature of it. For the amount of time I’ve spent around it, for the marine life I’ve had the opportunity to react and respond to—it’s amazing.

“From an intellectual point of view,” Humphries says, “the ocean’s vastness provides perspective on life and problems.

“And if you look at it the right way, it offers a form of hope.”

I would like to contact Emily Clapham about volunteering for her surf therapy program. I am a retired ESL teacher, elementary and middle school, 25+ years in public education, long time surfer, waterman, resident of South Kingstown, and URI alumnus ’79.

Thanks for your comment, Nicholas. I’ve passed your contact information on to Emily and she will reach out to you.